The final assembly line at Diamond Aircraft’s London, Ontario factory has six stations. You can walk the length of it in minute. For at least the past year, the only engines coming down that line are Jet-A fueled diesel powerplants from Austro and many of those have been the DA40 NG four-place single.

Improbable as it seemed in 2002 when the rollout of the diesel-powered DA42 stunned the Berlin Airshow, Diamond has proven unique among major airframe manufacturers for having not only survived with diesel engines, but thrived.

The DA42 made sense as a twin because the training market was starved for aircraft and once the warts were knocked off of it, it proved a popular airplane. But a diesel single? It would be heavier and more expensive than the competing avgas engine, a hard sell to buyers who talk the talk about wanting new engine technology, but get cold feet when the sales contract is to be signed.

The DA42 NG—NG for new generation, the name for the diesel version of Diamond’s four seater—has broken the mold. At a high if competitive price of $473,690, the company has found lively demand for the NG in the flight school world, so much so that the Lycoming-powered XLT ($439,800) hasn’t seen production since fall of 2018 in London.

When I visited the factory in chilly December 2019, the only gasoline engines in sight were in Lycoming crates in the engine build-up area. A parallel assembly line was building DA62 twins, also with the Austro engines.

TRAINING SWEET SPOT

With demand for airline pilots swelling, the trainer market has suddenly become hot, although the volume isn’t huge. The General Aviation Manufacturers Association doesn’t delineate sales by type of use, but Cessna appears to dominate the trainer market, with Piper in near second. In 2018, Diamond delivered 45 DA40s, most to the training market and most diesel powered.

The DA40 airframe first appeared in 1997 and entered serial production in 2001 at the company’s London factory. It had Lycoming’s popular 180-HP IO-360. The timing was right and Diamond enjoyed brisk initial sales.

At the same time, the company’s Austria-based skunk works was busy developing a twin based on the same fuselage plan, but powered by a pair of Thielert 1.7-liter turbocharged diesels based on the Mercedes Benz OM640 engine used in the A-Class sedans.

Although twin sales at the time were anemic, Diamond again got the timing right and by 2005, it had a full order book for the DA42, which proved popular for the training market because of its low operating costs.

But by 2007, minor mechanical issues dogged the engine and Thielert proved unable to sustain support under its warranty program. The company went into receivership in 2008 and very nearly took Diamond with it. The severe recession of 2008 didn’t help.

Unhappy with Thielert’s engine and especially factory support, Christian Dries, then owner of Diamond, started his own engine factory in 2007 adjacent to the company’s main plant in Wiener Neustadt, Austria. Thus was born the Austro engine, a four-cylinder turbodiesel based on the very same OM640 that Thielert had used for the Centurion engines it supplied to Diamond.

TWIN TO SINGLE

Although it got little notice, Diamond installed the Thielert engines in the DA40 as early as 2002, but the so-called DA40-TDI was never certified in the U.S. With its own engine available, Diamond switched new twin production to the Austro powerplants after having re-certified the aircraft in 2009.

A year later, the Austro AE300 engine—officially designated the E4—was certified in the DA40, but Diamond didn’t get serious about marketing it in the U.S. until recently because it believed with avgas widely available, North American buyers wouldn’t warm to diesels.

That was then, this is now. And now, the only singles coming down the line in London are diesel powered, although Lycoming models will resume this year. The company’s Austria factory also builds the diesel single, along with the DA42 NG twin. The London plant also builds the DA62 twin at the pace of a couple per month. Between Austria and London, Diamond has built a respectable 550 diesel singles.

Engines for the airplanes arrive in crates from Austria and are the latest iteration of the E4. In deciding to launch his own engine company, Christian Dries maintained that Thielert made two mistakes in adapting the Mercedes engine. First, to save weight, it used a cast aluminum block and head instead of the original cast iron and its warranty economics were poorly conceived and supported.

He insisted that Austro wouldn’t repeat the mistake and would capitalize on the millions of euros Mercedes invested in the engine by messing with it as little as possible. As a result, Austro’s production method uniquely received fully aircraft dressed automotive engines directly from the Mercedes engine plant and stripped off a handful of components. It then added on the components that transformed the engine into a certified aircraft powerplant.

These include a Bosch-developed electronic engine control unit, a new high-pressure fuel pump, an aviation-specific electrical harness with 28-volt starter and alternator, a redesigned engine sump and a new glow plug controller. Because automotive engines deliver their best torque at about 4000 RPM, the OM640 needs a gearbox to reduce that at 1.6 to 1, plus a prop governor.

On the Thielert engines, the gearbox was a sore spot because it required repetitive inspections at 300 hours and the parts had to be shipped back and forth from Germany. The gearbox also had a life limit and the engine itself had a 1200-hour TBR. Buyers weren’t thrilled that it had to be replaced, not overhauled.

The current iteration of the Austro has an 1800-hour TBO that Diamond says may be increased to 2100 hours sometime in 2020. Further, the engine can be overhauled at a price Austro has pegged at about $28,000—rough parity with the Lycoming IO-360. Field overhauls aren’t currently an option.

The engines have to be shipped to Austria for overhaul, so replacement/exchange is the maintenance model for the foreseeable future.

Rather than the Thielert’s troublesome clutch, the Austro engine has a dynamic torsional vibration damper that protects the prop against the engine’s sharp torque spikes. It requires inspection at 600-hour intervals. That’s done by removing the gearbox and testing the damper’s friction resistance. The gearbox itself is a lifetime part.

Austro’s deal with Mercedes Benz anticipated that the advancing automotive product cycle would leave the OM640 behind. In March 2019, it announced that it would begin manufacturing the engine’s primary structural components, including cast blocks and cylinder heads, on its own. The engines I saw at London were the last of the MB production.

HIGHER WEIGHT

Because of their higher peak cylinder pressures, diesel engines require more structure—and thus weight—than equivalent spark-ignition engines. For the Austro, the weight Delta is substantial: The Austro weighs 410 pounds against the Lycoming’s 279 pounds, a 131-pound difference.

On paper, that should have been a deal killer, but Diamond addressed it by simply certifying the NG at a higher weight: 2888 pounds for the diesel, versus 2535 for the avgas version. Of course, the empty weight is higher for the NG, but the useful loads are identical: 904 pounds for the NG against 900 for the avgas XLT.

The higher weight was approved primarily thanks to beefed-up landing gear. The NG meets stall speed requirements, but has a higher stall speed: 59 knots clean for the NG, 53 for the XLT.

The two airframes are nearly identical, with the exception of a foot shorter wingspan for the NG due to the use of winglets and two inches of additional length because of the Austro’s engine mount. With that much additional weight forward, you’d think the NG’s CG envelope is different and it is. At gross weight, the permissible CG envelope narrows from 5 inches to about 2.2 inches, meaning the NG is more sensitive to forward loading than the XLT is. (The XLT’s CG envelope is twice as wide at gross weight.)

Another way Diamond shaved the NG’s weight was to limit the fuel capacity to 41 gallons versus 51 for the XLT. The spec sheet lists 41 gallons as the long-range option and 30 as standard, but Diamond says all of the airplanes get the long-range tanks. Even with the lower total fuel, the NG has better range than the XLT because the NG burns less fuel.

FLIGHT IMPRESSIONS

I flew the NG with Diamond test pilot Jarred Curtis on a blustery, snowy day in London. Austro claims the engine is “automotive like” and it can be disconcerting that you can actually coax an engine to life sans incantations with mixture, fuel pumps and throttle position just so.

Just turn on the master and turn the key. The NG is equipped with the latest version of the Garmin G1000 NXi, which integrates power and engine instruments, including an indicator for glow plug heating.

The E4 has a pair of parallel electronic engine control units and it can run on either and actually does, with the engine software automatically alternating between the two. The EECUs operate on battery or ship’s power, but there’s also a dedicated backup battery that can run the EECUs and excite the alternator field winding, if necessary. A push-to-test switch runs the engine through its paces to check both EECUs and related systems.

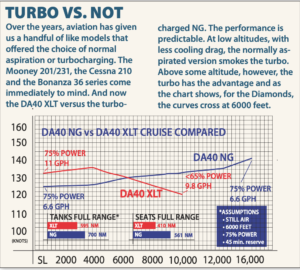

According to the POHs, at sea level, the gasoline XLT outperforms the NG slightly in takeoff distances and initial climb, but you’d only notice if the airplanes were side by side. You likely would notice it when the density altitudes are above, say, 6000 feet, where the NG’s turbocharger comes into its own.

For training operations, the NG is happy pottering around on 5 GPH and 115 knots. Burn a gallon more and it’s doing 120 at 4000 feet. Where the Lycoming will outrun the NG down low, it’s finished going fast by 6000 feet while the NG carries on all the way to 16,000 feet, where it will do 154 knots on 8.4 GPH. I’m sure many a curious student will drag it up that high, but with a portable oxygen system, a private owner might plumb the winter winds at that altitude and find 200 knots over the ground. You’ll stay comfortable doing it, too, because the NG’s heater will melt your sneakers.

As all airplanes should, the NG has a proper center stick perfectly positioned for fingertip control. On the downside, because of the stick and the over-the-front-wing ingress, the DA40 is not as easy to mount as a Cirrus or even a Cessna. And once in, it’s a little snugger, but the seats are comfortable and there’s an option for electrically adjustable rudder pedal position.

In past reviews, we’ve commented on how well sorted the DA40 is aerodynamically. This plays out in balanced control forces, a benign, predictable stall and something I had forgotten about: There’s hardly any pitch change when flaps are deployed, nor does the airplane seem to require a lot of fussy trimming.

The DA40 has an enviably low accident rate. I find only three fatal accidents among 739 DA40s on the U.S. registry. This is so low as to defy comprehension. No other model is even close. Besides the aforementioned handling traits, one other reason for this may be that Diamond’s decision to place the fuel in aluminum tanks between two hell-for-strong spars has resulted in practically zero incidence of post-crash fire. Another design point may also be a factor: Cockpit visibility in the DA40 is superb; the aeronautical equivalent of a fishbowl. Despite widespread use of traffic avoidance gear, you still have to see traffic to avoid it.

Selling diesel has proven to be an uphill fight in the U.S. Cessna gave up on it and conversion projects have similarly sputtered. Piper reports it has sold about 30 Archer DX diesels since it was introduced five years ago, but Diamond has sold twice as many just this year, not to mention another 70 diesel twins. I can’t guess whether this has to do with the airplane itself or an exceptionally adept sales force, so I’ll concede it’s probably both. As noted in the sidebar, U.S. flight schools may be waking up to the fact that the higher the training tempo, the more a diesel engine lowers total operating costs.

Further, good support from Austro may be ridding would-be buyers of the bad taste Thielert left when it entered the market with fanfare and exited in a crater. As the DA40 NG matures and finds buyers, that bad memory slowly recedes. For more, see www.diamondaircraft.com.