They’ve been around since before airplanes walked the planet. They’re simple—an air compressor that shoves more air into the engine so it can burn more fuel and produce more power. They were staples of many of the engines that gave World War II fighters, bombers and transports their impressive performance. Yet, for all their value, superchargers have largely faded from the general aviation scene.

Almost.

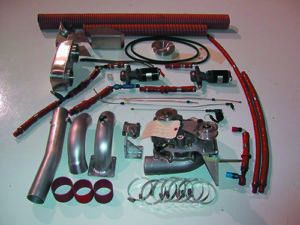

One company, Forced Aeromotive Technologies (www.forcedaeromotive.com), has been providing a bolt-on supercharger system for a gradually increasing variety of airplanes for more than 18 years. Currently it offers its mod for most Cessna 182s through the R model (including those that have a number of engine mods), Cirrus SR22s and Diamond DA40s as well as some homebuilts. The belt-driven supercharger provides sea level power up to 7000 feet density altitude. We took a look at the company and the system and liked what we saw.

BACKGROUND

Superchargers are air compressors directly driven by the engine via a belt, gears or the crankshaft. If the compressor is driven by a turbine spun by engine exhaust gases, the assembly is technically a turbosupercharger. Being American, we’ve shortened that name to turbocharger or simply turbo. The value of supercharging and turbocharging for airplanes has been recognized for over 100 years. In 1920 for example, the altitude record for airplanes was 33,114 feet, set by a World War I LUSAC-11 fighter with a turbocharged Liberty engine.

For general aviation airplanes, Cessna led the way into “blown” engines when it came out with the turbocharged Model 320 twin for the 1962 model year. It set the tone by increasing the horsepower above that of the normally aspirated version of the engine. Turbocharging proved popular quickly and all of the major manufacturers soon offered it. In return for big performance gains and the ability to operate in the flight levels, owners happily put up with the increased maintenance costs of a turbo system, largely a result of the heat involved with substantially compressing air as well as placing a turbine in the exhaust stream. A turbocharger at speed glows brightly enough to read a newspaper in a darkened dynamometer room.

Forced Aeromotive’s founder, Rod Sage, took a slightly different approach to boosting engine power for increased performance. His research indicated that the vast majority of owners of turbocharged airplanes never flew them above 12,500 feet. He also looked at performance numbers for turbocharged and normally aspirated versions of the same airplane and saw that, because of the back pressure in the exhaust system, the turbocharged airplanes did not perform as well as their normally aspirated brethren below 10,000 feet.

Sage was looking for the best of the normally aspirated and blown engine world when he developed a belt-driven (off of the accessory drive) supercharger that would allow the engine to develop its sea-level horsepower up to 7000 feet and 75% power at 12,000 feet. That meant that the supercharger would not be compressing the charge of air going into the induction system nearly to the degree that a turbocharger does on a system that allows full power to be developed to some 20,000 feet and increases the temperature of that air by over 200 degrees, often necessitating an intercooler to feed the engine air at an acceptable

INDUCTION AIR

Sage’s supercharging system increases the induction air temperature by no more than 60 degrees, providing a relatively cool, dense charge to the engine. As one person we discussed it with commented, “It’s gentleman’s supercharging.” That sounds right—the system doesn’t use the brute compressive force superchargers and turbochargers are capable of, so we think that it’s much less likely to cause the engine and exhaust wear common to more intensely boosted engines.

On that subject, Sage told us that in the 18 years he’s been providing the supercharger mod, no owner has reported the need for a cylinder change. The system is also much lighter than a turbocharger system: depending on the airplane, one-fourth to one-third the weight and about half the price.

Forced Aeromotive does installs at its Denver Centennial Airport home base as well as shipping complete kits for those who want to have the work done at their home shop. Sage told us that about half of his sales are overseas. He also said that buyers tend to be those who want the ability to operate in the mid-teens but don’t need to get into the flight levels. The substantially improved rate of climb has caused skydiving operators to be some of his best customers for the Cessna 182 mod.

The Diamond DA40 mod has only been out a little over a year, but Sage said that it’s proving popular in the West where the unmodified airplanes do not perform well in high and hot conditions.

PERFORMANCE

Forced Aeromotive’s website gives some performance data for the various mods, with cruise airspeeds improving 10 to 20 knots. Climb rate goes up as much as 500 FPM. Sage told us that airplanes with the supercharger mod outclimb normally aspirated and turbocharged models of the same type from sea level to 10,000 feet. That doesn’t surprise us as the supercharger requires only modest horsepower to turn, so it exacts little climb penalty where the exhaust backpressure in a turbocharged system significantly hurts performance below 10,000 feet.

The normally aspirated airplane will initially climb with the supercharged one, but within about 2000 feet of sea level, its power loss becomes noticeable. The supercharged machine continues to develop full power to 7000 feet, so its rate of climb increases with each 1000 feet above sea level until it reaches 7000 feet.

OPERATION

Operation of the supercharger system is dirt simple. No matter what the altitude, on takeoff the pilot firewalls the throttle. An electromagnetic valve (with a second acting as backup) opens when the target manifold pressure is reached: 29.6 inches in the Cirrus SR22, 28 inches in the Cessna 182.

Once the airplane reaches critical altitude—that altitude where the supercharger will not provide enough air for the engine to maintain sealevel power—the electromagnetic valve closes and all of the “charge” is directed to the engine. Manifold pressure then begins to drop at a rate of one inch per thousand feet.

Put bluntly, the supercharger system moves sea level to 7000 feet for an airplane with the mod.

The supercharger system is completely self-contained. In fact, it has its own oil system, so there is no need for a the supercharger to “spin down” after landing to avoid cooking it when the engine shuts down and its oil pressure goes to zero.

Installation takes 10-14 days. There is a few days’ lead time in ordering a kit as Sage’s company makes some components, such as hoses, at the last minute. The only additional maintenance requirement for an airplane with the mod is a 50-hour check of pulley torque and a 100-hour oil change.

DIAMOND DA40 MOD

We were particularly curious about the Diamond DA40 mod, primarily because we think supercharging smaller-engined airplanes can go a long ways toward bumping up their otherwise modest high and hot capabilites.

Californian Chris Keck recently went through the supercharger STC on his Diamond DA40. His comments: “I commute in the summers from San Carlos to Truckee, California. The cruise altitudes are 9,500 or 10,500, based on direction of flight. Before the install I didn’t get to altitude until almost Sacramento after takeoff from San Carlos.

“Now I am able to maintain a climb rate in excess of 800 FPM and get to altitude in one-third the time. Cruising at 11,500 feet with 24 inches of manifold pressure and 2400 RPM results in a TAS of 153 knots. Before the mod cruise was 135-140 knots TAS. Cruise at 17,500 feet, an altitude I never used until the mod, is now 135 knots TAS.

“The install was a problem as a piece provided by Forced Aeromotive did not provide enough room for the unit and needed to be fitted a second time. The install ended up costing $6000. I recommend contacting Forced Aeromotive as they say that they can do the install for $2000.

“Cylinder head temperatures have increased and require close monitoring. Overall, I’m glad I went forward with the mod.”

WARRANTY AND PRICING

The system comes with a six-year or 1800-hour warranty. Sage told us that he has never had to rebuild a supercharger—of some interest to those who figure on about 1000 hours before a turbocharger needs work, often teardown and rebuild.

For the Cessna 182 system, the price is $21,850. It weighs 31 pounds. The majority of the weight is between the firewall and the engine, so the balance change is minor.

For the Cirrus SR22 the price is $39,500 and the weight is under 40 pounds (how much under may vary depending on the individual airplane). The company also offers a replacement MT composite prop that mostly offsets the weight addition of the supercharger system.

The Diamond DA40 kit is priced at $30,150 and weighs 18 pounds.

Forced Aeromotive sells its supercharger mod for Cessna 182s that have had bigger engines dropped in them. It can be installed on the Continental O-470L, R, S and U, IO-550 and the PPonk engine mods.

CONCLUSION

Frankly, we think the Forced Aeromotive supercharger conversion is quite attractive for those who operate in the high country. It boosts performance nicely without the maintenance challenges of turbocharging.