Search the light twin market and inevitably you’ll come across Piper’s PA-23 series. But all PA-23 models certainly aren’t created equal and you won’t mistake an early Apache for a late-model Aztec—in looks or performance.

As far back as we can remember, the two airplanes generally serve different purposes. The Apache has long been used for initial twin-engine training and time building, while the Aztec works well as a go-places people hauler. Neither model is a speed demon, but both can be maintenance intensive given their age and complex systems. As you’d expect, you’ll pay a premium for good ones with mods and major upgrades.

MODEL HISTORY

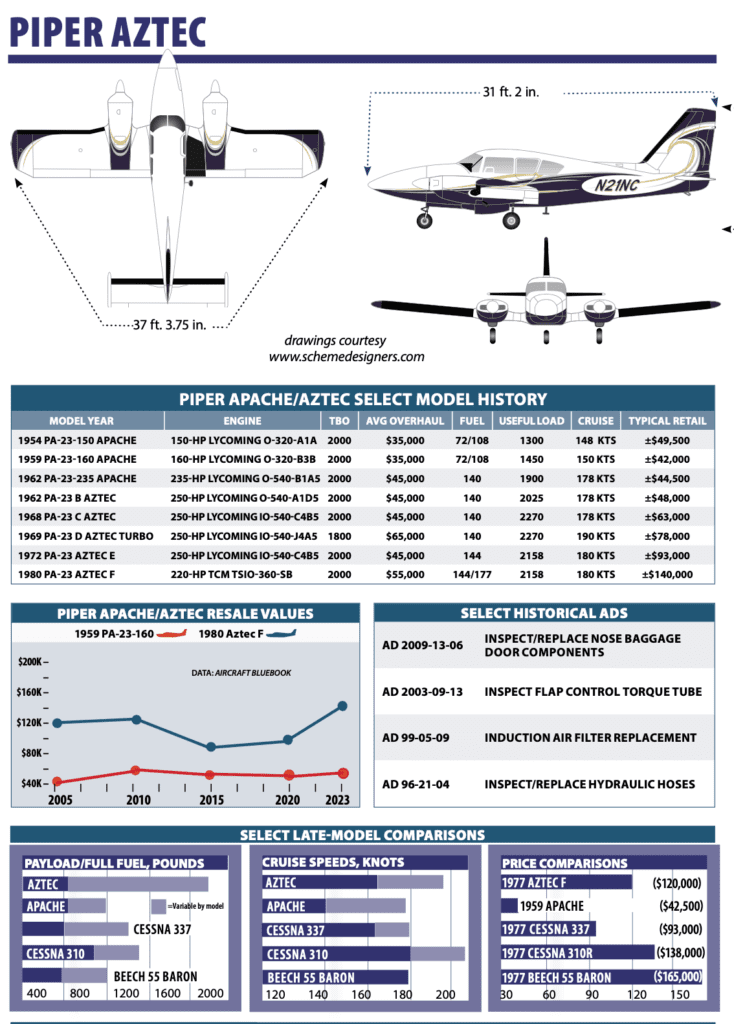

Flash back to somewhere around 1950 where the post-war boom had aircraft manufacturers in a race to build a personal light twin. Beech took the lead, and although Piper had been cranking out steel tube-and-fabric airplanes, it bought the Stinson Division of Consolidated Vultee. That created the Twin Stinson—a tube-and-fabric “executive” light twin with little 125-HP engines and a twin tail. Eventually covered in aluminum skin (and losing the twin tail), the airplane got two 150-HP engines and in 1954, the Piper Apache came to market.

The Apache had a fat constant-chord wing that made it work well for short runways, but its draggy stubby snout kept cruise speeds pretty slow—around 140 knots on a good day for a well-rigged airframe. Powered by two Lycoming O-320-A1A engines (150 HP), the Apache had a five-seat cabin and 3500-pound gross weight. Useful load was 1320 pounds.

Back in the day, the Apache typically retailed for around $36,000, and in the current market you might pay around $50,000 for one that’s in top shape. Trouble is, many that are used for training are kind of tired.

After a few years into production, Piper put more horsepower on the Apache—160 HP per side—using Lycoming O-320-B3B engines with full-feathering props. Along with the extra horses came a 300-pound gross weight increase, but the extra weight didn’t do much to help single-engine performance, which is lethargic at best.

The Aztec came along in 1960 and it had a stretched airframe, a bigger tail with a stabilator and 250-HP Lycoming O-540-A1B5 engines. With a max gross weight of 4800 pounds and more power, the Aztec killed Apache sales (the Apache was still offered in the Piper lineup) and in 1961 the company only made 28 of them, compared to 362 Aztecs.

Still, Piper wouldn’t let the Apache go and tried selling the airplane with O-540 engines, calling it the Apache 235. Meanwhile, the Aztec kept looking better (and sleeker), fitted with a longer nose with a baggage area. That 1962 B-model Aztec had six seats and an emergency exit window, plus optional fuel injection and turbochargers from AiResearch. Piper finally pulled the plug on the Apache in 1965 after making 114 airplanes.

Meanwhile, the Aztec kept getting better and in 1964 the C model got fuel injection as standard, plus a 5200-pound gross weight and eventual extension of engine TBO from 1200 to 2000 hours. In 1966, Piper offered the turbo version as a separate model rather than as an option on normally aspirated ones. The D-model Aztecs got a rearranged instrument panel layout and the E and F models got a nose extension. The pointier beak really steps up the ramp appeal, in our view, and it’s the easiest way to tell newer models from older ones. It was a decent run for the PA-23, with roughly 2300 Apaches and 5500 Aztecs delivered.

SYSTEMS, DWELLING

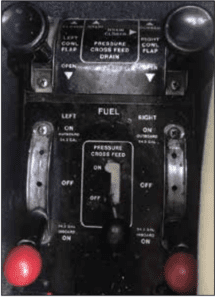

When searching for an Apache or Aztec (and when maintaining them), look closely for fuel leaks. All Apache 150s and 160s have one 36-gallon fuel bladder in each wing and you’ll find that many have an 18-gallon aux tank on each side. Apache 235s and Aztecs have two 36-gallon cells in each wing. The F model could also be fitted with 20-gallon internal tip tanks. Also on the Aztec F’s options list was an auxiliary hydraulic pump on the right engine. Earlier models came with only one pump on the left engine to operate landing gear and flaps.

If the left engine gives you the middle finger, there’s a hand pump underneath the control console that requires 30 to 50 strokes to get the gear up or down—a significant challenge during a real emergency. There’s also a CO2 bottle to blow the gear down if the emergency pump doesn’t work.

Something to seriously consider is that the landing gear and wing flaps are hydraulic and proven to be a source of leaks and constant upkeep. We heard from one owner who replaces some valves, hoses and fittings every year so that everything was changed over five to six years. Another told us he stocks a replacement gear pump, knowing he’ll use it at some unexpected time.

To check the level of the hydraulic fluid, the airplane must be up on jacks with the gear retracted and flaps extended. Otherwise, adding fluid overfills the system, leading to a very red airplane when the gear is retracted after takeoff. Some Apaches have been upgraded with dual alternators and vacuum pumps, and we would avoid those that have not.

For some aging models, the passenger cabin isn’t exactly a cozy dwelling. We’ve heard horror stories of heater issues, with one owner reporting his passengers had to wrap up in sleeping bags to stay warm during winter flights. That airplane turned out to have crushed heating ductwork requiring many hours of labor to fix and even then, the result was not adequate, despite also plugging the many leaks in the aft cabin bulkhead. Airflow in the fuselage is from the tailcone forward. Some models of the gas-fired heater have maximum hours between overhaul limits, so a Hobbs meter on the heater is a good investment as is budgeting big for an overhaul or replacement.

For hauling people, the fifth seat in Apaches and early Aztecs is relegated to the back of the cabin, where it takes up a lot of space in the 200-pound capacity baggage compartment. Some Apache owners might even remove the seat from the airplane, as it is virtually unusable and is just excess weight. Beginning with the B-model Aztec, there are three full rows of seats and 150-pound capacity baggage compartments fore and aft.

The PA-23 cabin is spacious and comfortable, with plenty of elbow, head and leg room. We’ve flown Aztecs on good-sized trips and attest that the airplane offers a decent ride. An Aztec can haul a respectable load, but don’t believe owners who suggest you can fly with anything you can close the doors on. Still, even well-equipped Apaches and Aztecs can carry full fuel, four or five adults and baggage, despite zero-fuel-weight restrictions imposed by an Airworthiness Directive (83-22-01) that was issued to prevent damage to wing-attach fittings.

The Apache 235 and the original Aztec have zero-fuel-weight limits of 4000 pounds. In naturally aspirated B through F models, any load above 4400 pounds must be fuel. For turbocharged models, the limit is bumped to 4500 pounds. We have found that a surprising number of owners are not aware of the limitation, so wing attach fittings should be a checklist item on a prebuy inspection. While there, check for corrosion in the tubes in the bottom of the fuselage.

PERFORMANCE

These are stable airplanes at slow speeds thanks to the fat, high-lift airfoil. But that shaves some speed. We’ve heard from owners of 150- and 160-HP Apaches that 135 to 145 knots on 16 GPH at 75 percent power is about right.

The big-engined Apache is faster but at more fuel burn. Realistically, figure on about 160 knots on 29 GPH at high cruise for the Apache 235. Early Aztecs claim 178 to 182 knots while burning about 26 to 28 GPH at 75 percent, but in our experience more realistic cruise is 160 to 165 knots. The E and F models are a few knots slower on the same fuel. Up high, around 24,000 feet, a Turbo Aztec can cook along at 190 to 200 knots at a thirsty 30 to 35 GPH.

These are good short-field machines, especially with VGs installed. The Apache models need less than 1100 feet to get in or out over a 50-foot obstacle, although the published Vx is very near Vmc. Early Aztecs require less than 1250 feet. Newer, heavier Aztecs use up a bit more pavement, but not much: Figure on about 2000 feet to get out and less than 1600 feet to get back in (over a 50-foot obstacle) in an E or F model.

Believe everything you’ve heard. Single-engine performance is on par with other small-engine light twins—which is lethargic. Published single-engine rates of climb vary from 180 FPM for the Apache to 160 to 240 FPM for the Apache 150 and naturally aspirated Aztecs.

The Apache 235 and Turbo Aztecs climb at about 220 FPM on one mill. However, some Apache owners have told us they’d consider themselves lucky to hold altitude at gross weight with only one engine running, and we saw barely 100 FPM while getting single-engine practice in a lightly loaded Apache 160 on a hot day. Then again, we felt a similar pucker factor climbing on one engine in a Seneca I. Practice it. A lot.

In our opinion, the edge of the single-engine performance envelope on light twins—those with normally aspirated engines of less than 200 HP—is really too close to being unsafe for comfort. There simply isn’t enough horsepower available to produce anything but a barely flyable airplane. A positive rate of climb depends on perfect technique and on top of these demands, the pilot is presented with the specter of engine-out handling difficulties, such as the tendency to roll over toward the dead engine.

On the other hand, the Apache is no worse than more modern designs. For example, Piper’s own PA-44 Seminole, a late-1970s design, has 180-HP engines and a useful load of about 1400 pounds. The original Apache, with 150-HP engines and a useful load of 1320 pounds, has a higher single-engine ceiling (5300 feet versus 3800 feet), higher service ceiling (17,000 feet against 15,000 feet) and better single-engine rate of climb (240 FPM versus 212 FPM). Proper recurrent training is the best protection against these shortcomings. It also helps to fly as much below gross weight as possible, and to install vortex generators—a worthy investment.

In the air, with everything working properly, the Apaches/Aztecs feel like big Cherokees, but with more responsive controls. However, the ailerons are somewhat heavier than the rudder and stabilator (elevator in early Apaches). One idiosyncrasy that will present itself to the transitioning pilot is the tendency of pre-1976 models to pitch up strenuously when flaps are lowered. It gets your attention. In 1966, Piper published a service letter (No. 474) suggesting the deployment of small amounts of flap, rather than stabilator trim, to counter nose-heaviness in the pattern; it works. The manual pitch trim control, by the way, is (like older Cherokees) a large crank on the ceiling with a smaller crank (a knob in later models) inside it for yaw trim; both are very sensitive. Another idiosyncrasy is the location of the gear lever on the right and the flap lever on the left of the center pedestal. Pilots do get these mixed up, and the latch that’s supposed to prevent inadvertent gear retraction doesn’t always work.

The ability of the bulbous airplanes to bleed off speed rapidly comes in handy when it’s time to get into landing configuration. Maximum speeds for lowering gear and flaps in Apaches built before 1960 are a ridiculously low 109 and 87 knots, respectively.

Limiting speeds in later models are a more manageable 130 and 109 knots. Also, in 1965, Piper came out with a modification kit for Aztecs and Apache 235s, allowing quarter-flap deployment at 139 knots and half flaps at 122 knots.

Pre-1971 Aztecs tend to thwart the pilot’s best attempts at trimming and roam a bit in altitude. A stronger stabilator down spring in the E model improves longitudinal stability, but control pressure in the flare suffers as a result. The stabilator and stabilator-balance system were changed with the introduction of the F model, but Piper later switched again from external to internal balance weights after AD 79-26-1 targeted cracks and attachment problems. Another change in the F model was incorporation of a flap-stabilator interconnect to reduce the pitch-up tendency.

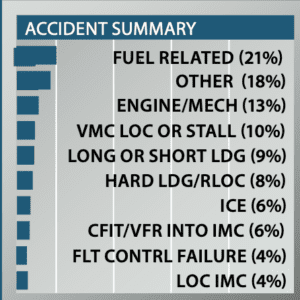

We have long thought of Piper’s PA-23-250 Aztec as one of the more air-kindly airplanes ever made. The chubby steel-tube structure and J-3 Cub airfoil may be the trailing edge of technology, but the result is amazingly forgiving to fly and completely honest on the ground. Our review of the 100 most recent Aztec accidents confirmed what we had long felt about the old beast—there were only four runway loss of control (RLOC) events and four hard landings. That’s miniscule in comparison to its peers.

Only one gear-up landing and two collapses spoke well of the gear design. However, there were several events in which the pilot’s lack of knowledge of the gear system caused an ignominious end to the flight. Some couldn’t figure out how to pump the gear down after having to shut down the engine that drove the single hydraulic pump and/or didn’t know that there was a second backup system—a CO2 blowdown arrangement.

One pilot shut down an engine and diverted to a nearby airport. He then flew so far away while he pumped the gear down that he couldn’t make the runway.

Where our eyes were painfully opened was in the ability of Aztec pilots and owners to operate—and maintain—the fuel system. Fully 21 percent of Aztec accidents involved pilots either running out of fuel completely, running a tank dry and not switching into one containing fuel, mispositioning fuel selectors or not draining contamination from the system. We were especially concerned to see five accidents in which the fuel system was a mess—water, rust, debris (Jimmy Hoffa’s body?), plugged filters, you name it.

Obscenely poor maintenance caused four failures of flight control systems inflight—uninspected aileron cables and stabilator trim actuators. In one case the NTSB described the situation with the airplane as “prolonged inadequate maintenance.”

Lousy maintenance didn’t just plague fuel and control systems, it was rampant in engine stoppages—most often cylinders that weren’t properly torqued after replacement. What made the mechanical and fuel-related engine stoppages worse was that fully half of the pilots who then wrecked their airplanes hadn’t feathered the prop on the dead engine. The Aztec may be a pussycat, but if the pilot doesn’t have rudimentary system knowledge and recurrent training, it will bite.

The capabilities of the Aztec may have caused several pilots to try to plunge into too much weather. Six lost battles with ice, including one who iced up the air filters of both engines—causing them to suffocate—and didn’t know the systems well enough to select the alternate air source to bring them back to life. Three decided that MDAs were for other people and descended into the ground well short of the runway.

An Aztec pilot noticed that one engine was “missing badly” and smoke was issuing from the cowling. He wisely shut it down and feathered the prop.

Not able to leave well enough alone, he later decided to restart the engine. As the prop came out of feather, the engine seized. The flight ended a few minutes later.

UPKEEP

Face it—like many others in the fleet, Apaches and Aztecs are old airplanes. That means parts can be either simple or difficult to source. We know firsthand (by wrenching our fair share of PA-23s) that some components should be stockpiled, while others are a phone call away. Salvage dealers are often a good source, and of course Piper is worth a try.

Don’t forget that many years of service can create lots of required inspections—and some are quite expensive. In our check of ADs for the PA-23, we found over 105 listed. One that may seem trivial but definitely worthy is 2009-13-06; it applies to all models with a nose baggage compartment and requires inspection and replacement of the door and latch components following fatal accidents resulting from a door coming open in flight.

Among the others on the list are: AD 63-12-2, on elevator butt ribs and doubler plates; 63-26-3, elevator and rudder castings; 72-21-1, control pedestal support bracket; 74-10-1, flap hinges; 78-2-3, stabilator tip tubes and weights (on Aztec F); 78-8-3, rudder hinge brackets (Apache 150 and 160); 78-2-3, stabilator or tip tubes and weights (on Aztec F); 78-8-3, rudder hinge brackets (Apache 150 and 160); 79-26-1, stabilators (most F models); 80-18-10, fuel selector valves and cables; 80-26-4, cabin entrance step support frame structure; 81-4-5, flap controls and hinges; 85-14-10, Hartzell blade clamps; and 88-21-7, fuel lines, caps and filler compartment covers. In many cases, the repetitive inspections are no longer necessary after affected parts are replaced or modified, but before buying, you should comb through the logbooks carefully with a shop or mechanic who knows the PA-23 well. The same goes for wrenching it once you own it. There’s a lot to these old twins.

GERONIMO MOD

Montana-based Diamond Aire (www.diamondaire.com) performs the worthy Geronimo mod, including a 180-HP Lycoming engine and prop conversion with an advertised 25-MPH speed increase. It also offers a number of other STC’d mods for the Apache-Aztec line including redesigned noses, dorsal fins, a speed-slope windshield, gap seals, vortex generators, tip tanks and inflatable door seals.

The company offers an instrument panel upgrade for Aztec, Apache and Geronimo models. The one-piece design eliminates clutter and is shock-mounted to isolate full panel. There are several panel styles with either backlighting or instrument post lighting, engine displays and dual center-stack radio configuration.

There’s also copilot brake pedals, dual-caliper brakes, engine nacelle and wing root fairings, cabin soundproofing, a throttle quadrant upgrade, fiberglass window moldings, a third-window upgrade kit, rear baggage area mod and power pack overhauls. There’s a lot more on the company website. Plan to spend a lot more for an Apache with Geronimo and these other mods. We think the upgrades really step the airplane up a few levels in performance and aesthetics.

Want to float your Aztec? You can do it with the Ontario, Canada-based Nomad Aztec (www.aztecnomad.com) straight-float seaplane conversion. With Lycoming IO-540s and 77-inch Hartzell feathering props it has a max useful load of 1800 pounds and an on-water takeoff distance of 1750 feet. At 75 percent power, the specs say it’ll cruise at 155 MPH on 29 GPH. We saw a couple for sale in Canada on the respected controller.com aircraft sales listing in the $325,000 range.

Considering the number of Aztecs built, it’s curious that there is no organization devoted to their owners. The Piper Apache Club (www.piper-apacheclub.com) caters to Apache owners primarily, but includes owners of all versions of the PA-23. There are also a couple of Apache/Aztec Facebook groups.

FEEDBACK

My wife and I have had the pleasure of owning two different Apaches. Our first was a 1955 PA-23-150 that had an updated panel and interior, but completely original airframe. It was a wonderful airplane to fly and while it was not going to blaze a path through the sky, you could carry quite a load and the cabin size was very comfortable. We would plan on 135 knots burning 14–15 GPH total.

Of course, single-engine performance was anemic, but the vast majority of our Midwest flying left the terrain well below the Apache’s drift-down altitude.

Maintaining a classic twin can quickly drain the wallet if an owner is not an A&P or actively involved with maintenance. The Apache is very well built, but ease of servicing may not have been a priority, as many maintenance tasks require a lot of labor.

For example, the original nacelles offer quick access to the engines, but to gain access to the oil screen one must drop the lower nacelle assembly. That task can take quite some time, leading many mechanics or owners to skip checking the oil screen.

Parts availability for some airframe parts can be a challenge, but the vast majority of consumable parts are readily available. There are quite a few ADs on the early airframes, but most of the ADs are inspection based and not egregious. The Hartzell propeller AD is a notable exception. If looking to purchase an Apache, I would seek out an aircraft that had the new-style props installed.

Our current Apache is a 1960 model with all of the Geronimo mods. It has the O-360 (180 HP), long nose with baggage, aux electric hydraulic pump, aft baggage, flap gap seals, aux fuel tanks (108 gallons total), squared-off tail and fiberglass nacelles. We flight plan for 150 knots burning 18–20 GPH total.

As much of an Apache purist as I was when we had our 1955 Apache, the Geronimo is a better aircraft. It is faster, carries more and is easier to maintain. The new-style nacelles allow total access to the engines in less than five minutes.

Parts support for the Geronimo mods is excellent. John Tamage of Diamond Aire in Montana (the current holder of the Geronimo STCs) has always been very responsive about parts or support. I would also highly recommend an Apache owner join the Piper Apache Club run by John Lumly. The forum is a fantastic resource for parts and maintenance advice.

Our Geronimo has a modern panel centered on the Garmin G500 driven by a GNS 430W. We added a GDL 69 for weather and installed PlanePower dual alternators to supply adequate and consistent power. For fuel efficiency and cost in a twin, it’s hard to beat the Geronimo.

Florian Kapp – via email

I stepped up to a Piper Aztec after owning a Piper Cherokee Six for a number of years. While searching the market, I came close to buying a Piper Seneca II, but my mechanic scared me away from it because of the turbocharged engines.

I later settled on an E-model Aztec with a good service history, and I’m not sure the airplane is any easier on maintenance. Buyers need to understand that these are old twins with complex systems. I’ve owned the airplane for four years now and like to think I’ve paid for my share of intense annual inspections (priced at around $9000 to $12,000 every year) and unscheduled repairs, including landing gear accessories, heater repairs and a whopping $3500 autopilot repair.

As you guys have been reporting, my insurance premiums are going up and before I get any older I’m thinking of getting back into a Cherokee Six—an airplane I should have kept all along.

Will Danatto – vie email