At 15 months since the professional application of the System X Element 119 ceramic coating product on my Grumman Tiger, I was anxious to see how it was holding up. The aircraft was painted in November 2020 with a basecoat clearcoat finish (see the January 2021 Aviation Consumer for a report) and I had to wait the required five months before applying anything to it.

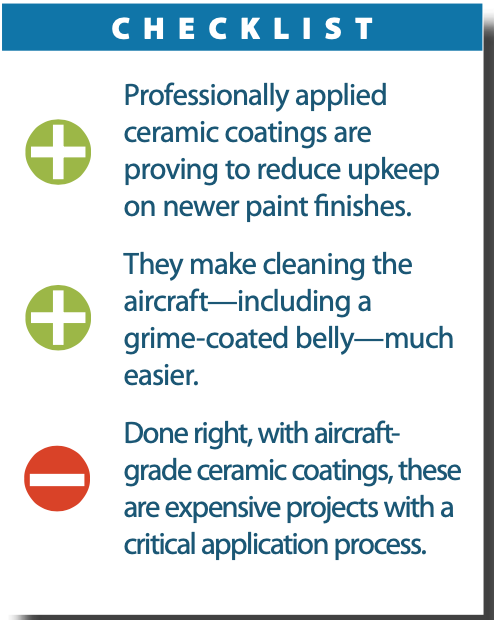

While the results were nothing short of spectacular, the real test would be to see how long the stuff actually lasts. Skeptical of claims that you can go five to seven years between applications, so far I’m not disappointed.

THE BRUTAL TEST

Since the ceramic application is a critical process with climate-controlled curing, I took it to a pro—Dan Lightner at NuAero Detailing in Pennsylvania (www.nuaerodetailing.com)—for the work. System X comes in several different grades. We used top-of-the-line Diamond on the upper surfaces that are exposed to direct sunlight and the less expensive Renegade product on the underside. These aircraft-specific products are expensive—$600 (wholesale) to cover the Grumman, plus labor.

To put System X to the most brutal test at my disposal, the Tiger was flown 275 flight hours over 15 months—including two trips from Pennsylvania to the Bahamas, where the aircraft sat in the scorching sun. We didn’t even wash the plane. Occasionally, the leading edges and windshield were spritzed with water and given a microfiber towel wipe down. Even bugs that were months old easily wiped away. We also noted that summer bug accumulation was quite a bit less with ceramic coating than in previous years when the finish was coated with sealers and wax. A caveat: Ceramics are designed to protect the finish, not enhance it. Therefore, the better the original finish, the better the final appearance. Ceramics won’t restore a decades-old ragged finish and won’t hide scratches or flaws in the paint. But it sure does shine.

The main component of ceramic coatings is silicon dioxide (SiO2), which is also a major component in glass—hence the glass-like appearance. With its nonporous cure, filling properties and high resilience, ceramics offer protection from surface oxidation, parasitic drag and UV damage. Having flown this Tiger for 22 years, I noted a real-world 3- to- 5-knot increase in cruise speed with the new paint and ceramic. Fellow Grumman owner, Cindy Aulbach, had her Traveler professionally ceramic coated while hangared at the September 2021 Grumman Convention by NuAero. A year later, Cindy calls the ceramic “spectacular, with the money we’ll spent.” Her only complaint is that it’s hard to wash because the water just beads up and runs off the plane before she can grab the sponge and wipe it. That’s not exactly a bad problem.

THE DAY OF RECKONING

Detailer Dan Lightner met me at my hangar in mid-July to see the condition of the ceramic under months of accumulated dust and dirt from the adjacent farmers’ fields. Dan agreed that allowing the ceramic to sit 15 months without a single wash was an extreme measure. Rather than my typical wash with soap and water, Dan convinced me to try a dry wash.

Beforehand, out of curiosity, I poured a gallon of water on the wing to ascertain any remaining beading action. The wing beaded like the finish had been applied yesterday. The beading action of wax and sealers is generally gone by 6 months or less and this was three times that.

Due to the amount of dust and dirt, Dan and his partner, using Granitize Hard Surface Cleaner XG5-G, went over the entire airframe applying a liberal amount of cleaner to avoid scratching the paint. Then they made a second pass using Granitize Spray and Shine XC11-G, a milder cleaning agent. As a professional detailer, Dan highly recommends both of these products, as we’ll as Dawn Powerwash for really stubborn dirt.

What impressed me the most was the ease with which the belly cleaned up. The underside of all piston aircraft is fraught with carbon, soot, grease and oil. With ceramic protection it’s a simple matter of spraying and wiping. The belly was clean with no elbow grease. It’s truly impressive. Once the entire plane was dry washed, Dan assured me that the ceramic was fully intact and no touch-up was needed.

Another aircraft in our test fleet, a Pilatus PC-12, was professionally coated with the Sapphire V1 Nano ceramic coating. A large turboprop like a Pilatus requires 10 50-ml bottles of product. Ordering a bit extra, 12 bottles is a $1500 investment. The total job for the Pilatus was a whopping $6000. Over a year later, owner Al Simmons remains impressed with the overall finish and the product’s longevity.

Simmons advised not to use the coating on stainless steel exhaust pipes. The Sapphire product created a strong barrier that made it extremely difficult to remove some discoloring that appeared on the airplane’s pipes (not apparently caused by the coating). The thing to remember is that ceramic coating is semi-permanent. Once it’s on, it’s really on, and it will take serious elbow grease to remove.

On the Pilatus (the paint finish is over 13 years old, but extremely we’ll cared for) you don’t have some of the same issues of blow-by oil and grime that accumulates on the belly like it does on a piston-powered airplane. But there are areas that collect black soot (on the front cowling) and with the ceramic protection in place, the soot comes off when flying through rain.

“We recently washed the airplane with an aircraft-specific wet wash and it was pretty much effortless, with all of the dirt coming off easily and overall, the aircraft looked great,” Simmons reports. The aircraft was previously washed almost seven months prior, proving again that a ceramic finish greatly reduces upkeep.

Worth noting is that small areas on this aircraft were recently spot-treated for corrosion, which involved light sanding, paint blending and new clearcoating. Those areas (without the ceramic coating) get dirtier and the water doesn’t bead like it does on the ceramic-coated areas.

“We’re glad we invested in the ceramic finish and so far there is no indication that the finish is wearing out,” Simmons said.

DON’T TRY IT AT HOME

Unanimously, folks we talked with who have made the big investment (some after failing when trying it themselves) said that a professionally applied coating is absolutely imperative. Because the formulation is made to last a long time (containing a higher concentration of SiO2 than cheaper spray-on coatings used in the auto retail market), there is very little margin for error. This includes applying the right amount of product in a given area and also allowing the finish to cure in the right temperatures.

Also worth mentioning is that pro detailers likely have access to ceramic products typically unavailable to the consumer. They also have access to a variety of tools to get the job done right. But you’ll pay for a pro job. We’re finding that ceramic projects on typical light pistons and twins generally cost $2000-$3000, on average, while larger turboprops and jets are $6000 and up.

Ceramics are everything they are purported to be when professionally applied and, in our estimation, worth the big investment.