Phase 1 of the FAA’s plan to decommission over one-third of the nation’s VORs will be complete later this year, by the end of September. Then, Phase 2 begins immediately to continue scrapping VORs at the rate of almost one a week.

While the chances are good (but not 100 percent) that your navigator’s data is keeping up with the changes, you need to backstop it, which is easier said than done.

REPLACED BY GPS

Let’s face it. VORs are obsolete, not just technologically, but operationally as well. When was the last time you used one to actually, you know, navigate? Even if you don’t have one of those fancy GPS magic wonder boxes in your panel, you almost certainly have one on your lap and you use that for navigation. Fact is, we’re just not using VOR navigation. If you’re instrument rated, check back in your logbook. If you’re like most of us, the last time you flew a VOR approach was on your last IPC, and the time before that was on the IPC before that. We just don’t need VORs anymore … until we do (but we’ll get back to that).

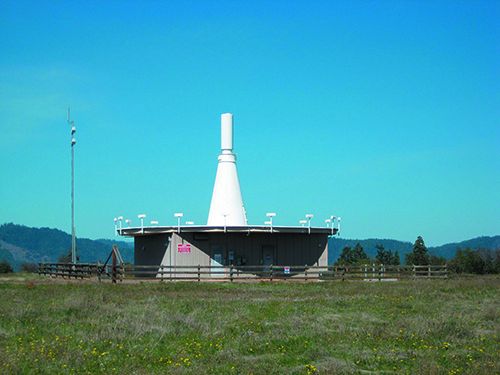

VOR ground station hardware—housed in those odd-looking, sombrero-shaped, white buildings in the middle of remote fields—is largely obsolete, with nearly 90 percent of them past their original 30-year expected lifespan. Since we don’t use them anyway, and the hardware needs to be replaced, why bother? There’s good argument to get rid of them, and that’s what the FAA is doing.

The FAA knows we prefer to use simpler and quicker GPS navigation. But, they also know that GPS isn’t quite as reliable as we might like, what with government agency after agency degrading or simply interfering with those fragile satellite signals. Depending on where you live, you might get multiple notices every few days that somebody’s messing with GPS in your area.

Then there’s the specter of a large-scale outage. This won’t likely be for reasons of equipment failure, but is considered a real possibility from national disasters and/or deliberate interference from an outside actor. To accommodate the possibility of a large-scale GPS outage, the FAA has decided to reduce existing VORs down to a Minimum Operating Network (MON) of 585 VORs by 2025. Those remaining VORs will be sufficient to get you to an airport where you can land in good weather or use an approach not relying on GPS. Meanwhile, getting to a MON airspace means VORs are dropping left and right.

GONE, NOT FORGOTTEN

A number of things must happen when a VOR is decommissioned. Any associated airways, fixes and procedures must first be either redesigned or retired as well. Only then can the VOR itself be taken out of service. This involves adjusting the defining data to identify it as decommissioned while removing it from all the charts. Note that the VOR data entry isn’t necessarily removed from the FAA database, but instead the status is changed to show that the navaid was decommissioned. That’s a potential gotcha. And of course, this official FAA data is at the heart of the various data sources like Jeppesen, Garmin, Seattle Avionics and others.

Certified, panel-mount avionics must use certified data. This data goes through rigorous quality assurance processing to ensure it is as error-free as possible before it is ever available to load into your navigator. While some vendors use similar quality assurance processes on data destined for non-certified EFBs, not all do, or their processes might leave possible errors undetected. It’s inevitable errors like this that spawned this article.

As an example, but by no means to single it out, Garmin Pilot knits together multiple sources of nav data. First, of course, U.S. data originates with the FAA. But, Pilot also includes worldwide data from other sources. Not all data sources are of the same quality, and occasionally a VOR that was deleted from the U.S. data might still exist in data from another source and, as a result, it can get reintroduced into the complete nav data package used by Pilot.

We regularly fly a route from Santa Fe, New Mexico (KSAF), to Byron, California (C83), so rather than re-create this route every time, like many folks, we created a stored route to reuse. Within that route was the Manteca VOR (ECA) just east of Byron. In 2018, ECA was decommissioned and removed from FAA data.

Unfortunately, it remained in some other data sources with the result that it remained in the nav data used by Pilot. This meant that you could still flight plan using ECA in the underlying nav data, even though it was long gone from the charts.

Garmin did have a process in place to “blacklist” fixes like ECA, but it relied on fallible and not-necessarily-timely human input. After our inquiry about this, Garmin changed their data processing to prevent deleted fixes in the FAA data from being reintroduced to the entire data set from another source. We made inquiries about this with the other major EFB vendors. ForeFlight says it uses Jeppesen data that is rarely subject to these kinds of errors. Seattle Software also said their data is the same as is used for certified navigators, thus is mostly immune.

Hilton Software’s WingX still, as of late November, shows ECA in the data and didn’t respond to either of our two inquiries.

PROBLEMS CAUSED

There are a few implications from all this. First, let’s take the case of the lingering ECA as we experienced. Because ECA still existed (as it still does in WingX) in the nav data, using a stored route with a fix like this is perfectly acceptable to the system; you’ll never know there’s a problem unless you carefully review the stored route on the charts and notice that the EFB placed a fix on the route that’s gone from the charts.

So, you happily complete your flight planning and get ready to fly. When you try to put this route into your navigator, though, an error should result. Also, since you probably filed the flight plan from that EFB, but with that obsolete fix, the flight plan was likely rejected. If you catch this error before calling for your clearance on the ground, the implications are minimal.

However, if you are in a hurry, like we were when we tripped over this, and you try to pick up a clearance on the go after departure, you might be in for a rude surprise requiring a good deal of scrambling to remedy.

But, there’s a potential for bigger issues that could affect all the EFBs and even your certified navigator. Do you use stored routes? What will happen if the stored route has a fix that has since been deleted? Do you know?

The behavior of each system can be different, so analyzing that behavior of each EFB and each navigator is beyond what we could do. That means you should research this with your own devices. And, doing that research won’t necessarily be easy unless you’ve already got a route with a decommissioned fix.

If you don’t have such a route, you’ll have to create one. But, based on what the EFB vendors told us, unless you’re using WingX, it’s likely you won’t be able to create a route with a deleted fix, so you won’t be able to store one.

If that’s the case, you might have to dig though the manuals or contact the vendor for guidance.

Since this is an edge case, the behavior of your specific device might not be obvious when it encounters a fix on a stored route that isn’t in the current data.

One would assume that the stored route merely stores the fixes and possibly airways, so the system won’t recognize a deleted resource when you try to load the stored route. But, if the stored route also stores the nav data associated, there might be no way to detect this problem. Thus, it is incumbent on you to know the behavior in advance.

THE BOTTOM LINE

To review, there are two underlying problems that can crop up with fixes that have been deleted. 1) Even though the fix will surely be gone from the charts, the fix might erroneously remain in your underlying nav data and using it will be perfectly acceptable to the device when importing a stored route with that deleted fix. 2) The fix might indeed have been removed, but your device doesn’t adequately detect that or warn you when importing a stored route containing that deleted fix. Note that both of these stem from the use of a stored route.

To minimize the likelihood you’ll ever trip over this you could just avoid using stored routes, both in your EFB and in your navigator. But that’s pretty drastic.

A better idea might be to carefully examine those stored routes as part of your planning, and deliberately verify each fix and each airway used on the route.

That verification should be done against current charts, as displayed on your EFB or your navigator if it displays all that, or even paper charts, if you still use any. This verification step has the added advantage of refamiliarizing yourself with the route. Along the way, you might even find something you want to change.

Last, of course, as we discussed above, know how your device behaves when it encounters an obsolete element in a stored route. With all these precautions, even with the FAA deleting almost one VOR a week, it’s not likely you’ll be calling for a clearance in flight, only to be told that there’s no clearance available. At least, not for the reasons of you filing an obsolete fix.