As a variation on the tired trope about not being able to afford something if you have to ask its price, we offer this: If you want a detailed understanding of all there is to know about the myriad models of Pratt & Whitney’s workhorse PT-6 turbine, you’d need a career change just to frame the question. If variety is the spice of life, the PT-6 is off-scale high on the Scoville index.

Daunting or not, PT-6s eventually have to be overhauled and the market for such services is competitive and well-served, albeit structured a bit differently than the piston-engine overhaul world. Given the complexity, newbie PT-6 owners—and there appear to be more every year—may be unavoidably dependent on advice from shops which either specialize in aircraft powered by the PT-6 or, better yet, independent consultants who understand these unique engines.

Because turbine overhauls are so expensive—think the price of a recent model used Cirrus—the value of the airframe is more tightly linked to decisions about renewing the engines. For some aircraft, it might be quite possible to put the airplane’s value completely underwater through a wrong decision on engine overhauls.

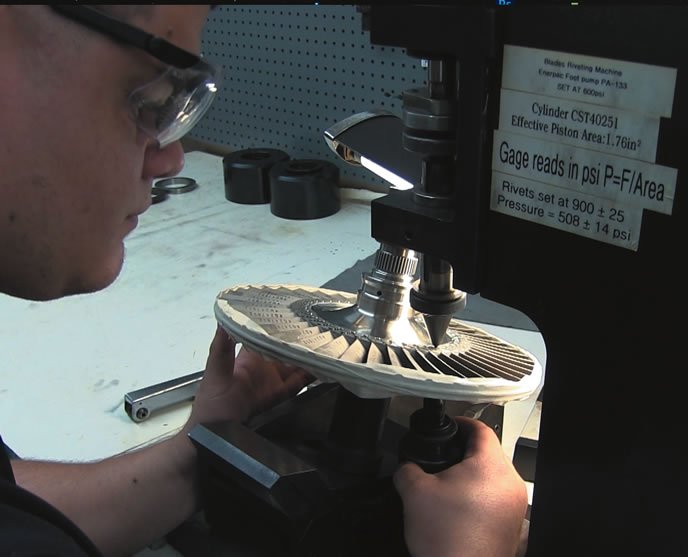

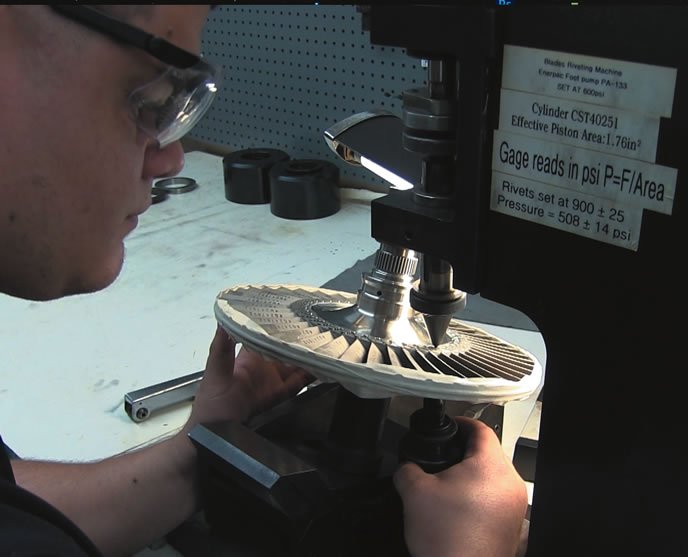

In this article, we’ll examine what’s involved in a PT-6 overhaul through a visit to United Turbine near Miami, an established PT-6 shop recently bought by the Continental Motors group. We also talked to companies specializing in turbines about their recommendations on PT-6 overhauls.

Late to the Party

During World War II and in the years immediately following the end of it, Pratt & Whitney Canada was a stalwart in the military and airline piston market, supplying a range of engines with a tilt toward British-designed aircraft. But when the jet age arrived, again led by developments in Great Britain, P&WC lagged behind Rolls-Royce, General Electric and the company’s own U.S. division, where jet development built rapidly on captured German technology. While PW&C did develop a turbojet as early as the mid-1950s, for lack of funds and manpower, it was taken over and completed by the U.S. mothership to become the JT12. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

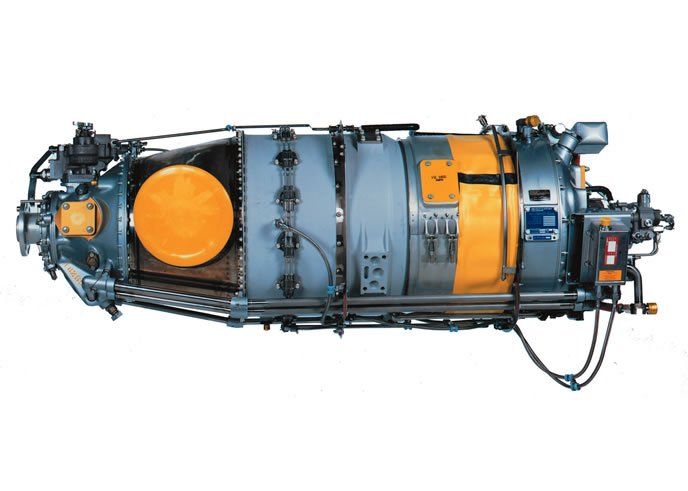

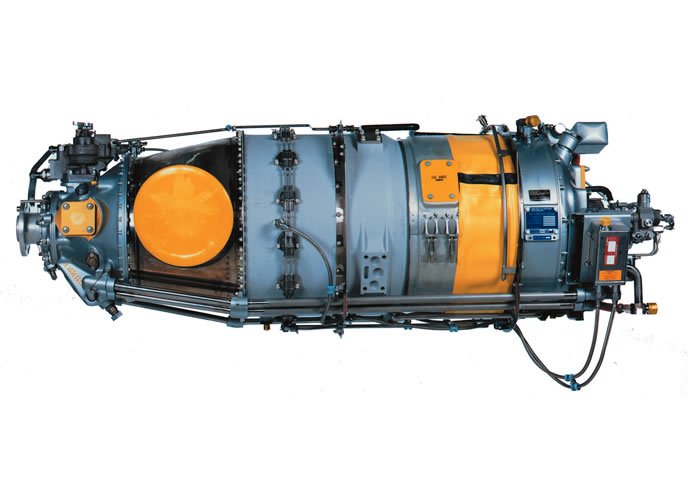

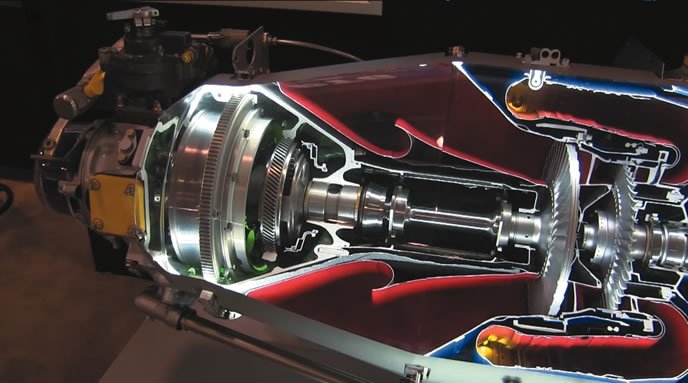

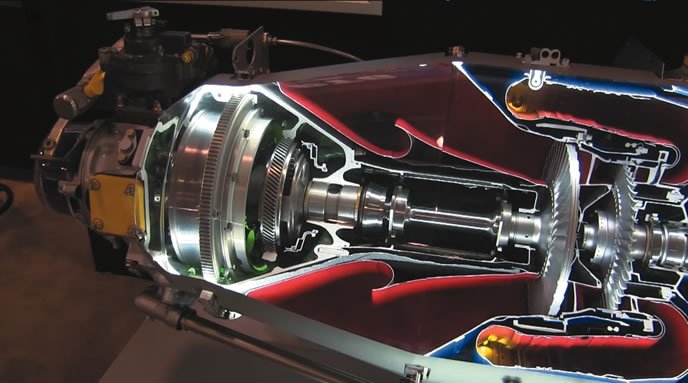

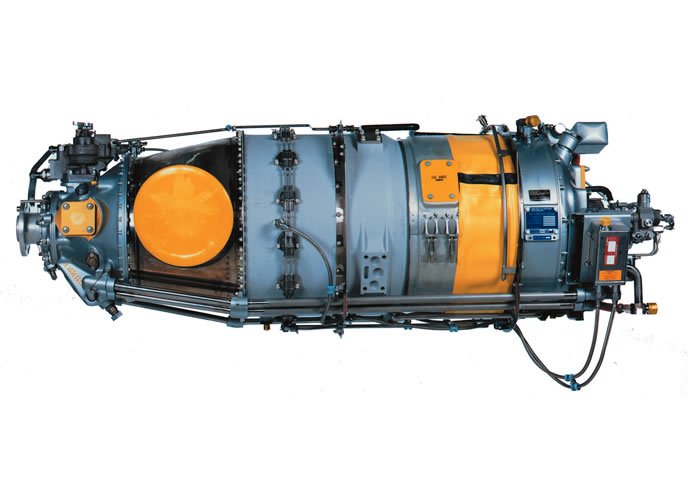

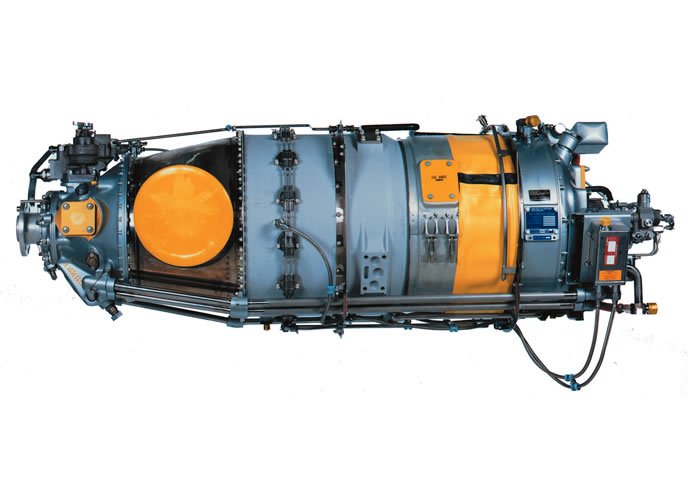

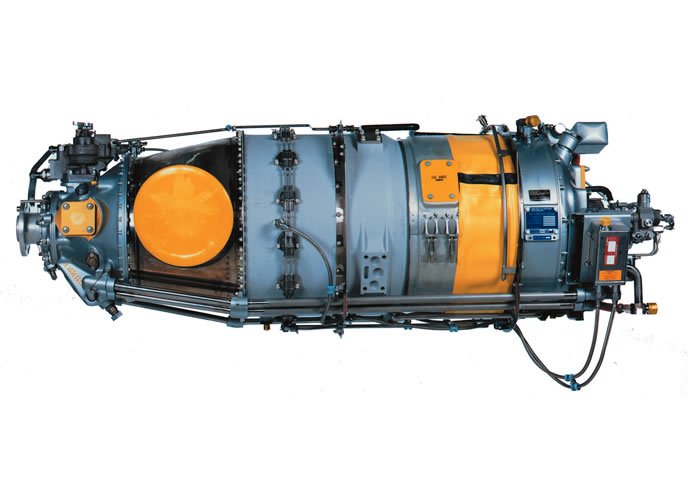

While GE, Allison and Rolls-Royce had a lock on the emerging turboprop market, P&WC noticed there was a gap in the 250- to 1000-HP range and both the military and civil companies such as Piper were considering airframes requiring such engines. In 1958, P&WC developed a spec for the engine and by 1963, it had certified what became the PT-6, an engine that today dominates the low- and mid-horsepower market and which proved scalable and flexible. After months of deliberation, Pratt developed a free-turbine design which means that the engine consists of two major segments—a turbine/compressor section or gas generator that produces high-energy gas flow and a power turbine section that generates rotational motion from the heated gas. A third component, a two-stage gearbox, reduces the power turbine’s 35,000 RPM to something more prop friendly. Other than a small seal between them, there is no physical connection between the gas generator and the power turbine.

As P&WC saw it, the free turbine design was more complex to manufacture, but required less starting energy, hence it could self-start easily without ground support and it could have simpler fuel controls. Furthermore, while turboshaft engines require expensive, dedicated propellers, a free turbine does not and in the event of an engine failure, a free turbine exacts less drag than a turboshaft does and compared to its arch competitor, the Garrett TPE331, the PT-6 is much quieter on the ground.

Overhauls: What’s Required

Just as the PT-6 is available in staggering variety, so too do its TBOs and overhaul specs differ. For this article, we’ll address the lower power variants of the PT-6A series—the -21,-135,-28, -112, -144 and the -42A found in aircraft like the King Air 90 series, the Cessna 425 Conquest, the Caravan, and Piper Meridians and Cheyennes.

Generally, when it emerges from the factory, a new PT-6 is considered a 3600-hour engine, with a mid-time TBO on the hot section—the burner can and power turbine—at the mid-point. However, a so-called “hot” is really just an inspection, not a required overhaul. And work on the hot section at that stage is based on condition, although those familiar with the PT-6 tell us that hot inspections usually uncover at least something that needs fixing and sometimes they require high-dollar repairs or replacements, especially on engines operated in humid or dusty environments.

The major components mentioned above each contain complex parts that require attention at overhaul and some have different time requirements for inspection or replacement. The gas generator section consists of compressor turbines—three axial and one centrifugal wheel for the smaller engines—and the burner where fuel is mixed with the compressed air to generate hot gas.

For the smaller horsepower PT-6s, the power turbine, or PT, is a single wheel connected to a complex, two-stage planetary gear reduction section which, again, carries its own overhaul and inspection requirements that aren’t the same as the engine itself or that of other components.

When applied to the PT-6, “overhaul” is somewhat of a fuzzy term. Overhaul times can be extended or adjusted through the use of trend monitoring programs that carefully track the wear of critical items. Such programs don’t make the engine immortal, exactly, but they obviate teardowns at specific intervals just to see what’s inside that might need work.

And at this juncture, expert guidance is needed. An owner looking at a serviceable airframe—say an older King Air C90 or a Cessna Conquest I with run-out engines needs to tread cautiously indeed. In all their infinite variety, PT-6s also have a stack of service bulletins that shops and operators must be cognizant of. Throughout our conversations with PT-6 experts and operators, we constantly heard cautions about knowing the service bulletin level before digging into PT-6 ownership or overhaul.

“You can take a pair of engines and put them into a shop and not really know what it’s going to cost to get them back out. That’s a heart attack. How do you plan for that? Worse, you’re stuck doing the overhauls and maybe you get back a set of engines that you’re going to have to throw away the next time,” says Conrad Jones of Kansas Aircraft, a brokerage and maintenance house

that specializes in turbine aircraft. As with piston engines, the variability in what an overhaul might require and what it might cost is considerable, but the actual dollar values can be much higher—into the six figures.

“From the consumer perspective, we’ve had customers say, ‘I really like your airplane, but I’m scared to death with the unknowns related to the PT-6, especially on the King Air 200, where you have service bulletins on the PT [power turbine] discs that can really drive the prices up,” says Michael O’Keeffe of Banyan Air Service, another company that specializes in turbines.

For all its reliability and power, the PT-6 can be a bit of a Pandora’s box. Even if the airplane has good logbooks and the service bulletin status can be determined ahead of time, the unknowns when the engine is opened up and inspected can reveal expensive repairs and replacements. “You really can’t know what it’s going to cost until you’ve got them off the airplane, disassembled and inspected and by then, it’s almost too late to make a decision,” says Kansas Aircraft’s Jones. And the decision would be to find used engines on the open market, opt for the Blackhawk conversion (see sidebar at right) or even new engines from P&WC if the airframe justifies that kind of expenditure. Some do, some don’t. But the fantasy of buying a nice King Air or Conquest with run outs for a song and re-engining it to own a bargain turboprop is, well, probably a fantasy.

“As a company specializing in resale,” says Banyan’s O’Keeffe, “to take an airplane with runouts and overhaul them to sell it is very difficult.” PT-6 overhauls have simply escalated so much during the past decade, that “reasonable” and “overhaul” may not appear in the same sentence. Although factory overhauls are the most expensive, non-factory overhauls have also kept pace, even if they can be 15 to 20 percent lower than the factory numbers.

And not all factory-approved shops provide exactly the same services or the same prices, says Paul Jones of Specialty Turbine Services, a company that provides turbine pre-buy and overhaul consultation. “We brief our clients on what to expect on an overhaul. For example, if it’s the first overhaul, they reinstall the compressor turbine blades. That’s always in exclusion in the estimate the shops provide, yet it’s a $100,000 part,” says Jones.

that specializes in turbine aircraft. As with piston engines, the variability in what an overhaul might require and what it might cost is considerable, but the actual dollar values can be much higher—into the six figures.

“From the consumer perspective, we’ve had customers say, ‘I really like your airplane, but I’m scared to death with the unknowns related to the PT-6, especially on the King Air 200, where you have service bulletins on the PT [power turbine] discs that can really drive the prices up,” says Michael O’Keeffe of Banyan Air Service, another company that specializes in turbines.

For all its reliability and power, the PT-6 can be a bit of a Pandora’s box. Even if the airplane has good logbooks and the service bulletin status can be determined ahead of time, the unknowns when the engine is opened up and inspected can reveal expensive repairs and replacements. “You really can’t know what it’s going to cost until you’ve got them off the airplane, disassembled and inspected and by then, it’s almost too late to make a decision,” says Kansas Aircraft’s Jones. And the decision would be to find used engines on the open market, opt for the Blackhawk conversion (see sidebar at right) or even new engines from P&WC if the airframe justifies that kind of expenditure. Some do, some don’t. But the fantasy of buying a nice King Air or Conquest with run outs for a song and re-engining it to own a bargain turboprop is, well, probably a fantasy.

“As a company specializing in resale,” says Banyan’s O’Keeffe, “to take an airplane with runouts and overhaul them to sell it is very difficult.” PT-6 overhauls have simply escalated so much during the past decade, that “reasonable” and “overhaul” may not appear in the same sentence. Although factory overhauls are the most expensive, non-factory overhauls have also kept pace, even if they can be 15 to 20 percent lower than the factory numbers.

And not all factory-approved shops provide exactly the same services or the same prices, says Paul Jones of Specialty Turbine Services, a company that provides turbine pre-buy and overhaul consultation. “We brief our clients on what to expect on an overhaul. For example, if it’s the first overhaul, they reinstall the compressor turbine blades. That’s always in exclusion in the estimate the shops provide, yet it’s a $100,000 part,” says Jones.

Factory vs. Non-factory

Of course, getting the factory numbers is difficult because P&WC’s official policy is not to quote prices; not even ranges. This is understandable given that the condition of the engine and its service bulletin status will determine the bottom line price and that can’t be assessed before the engine is opened up. P&WC has three designated overhaul facilities or DOFs, one in St. Hubert, Canada, one in Bridgeport, West Virginia and one in Ludwigsfeld, Germany. In addition, there are another five approved maintenance facilities in the U.S. that can provide factory-approved overhaul services. P&WC has a range of options for its overhaul customers, including exchange engines, loaner engines and TBO extension programs for high-utilization operators.

Shops familiar with both factory and field or alternative overhaul options for the PT-6 say it’s difficult to compare the two options in terms of what new parts are used, nor does it necessarily matter for the quality of the overhaul. P&WC told us that its factory overhauls include these new parts: compressor turbine vane ring, power turbine vane ring, third-stage compressor stator and spacer, first-stage compressor blades, impeller housing amd the compressor bleed-off valve, to name most of the major parts.

However, both factory and field overhauls may contain reconditioned or repaired parts, as allowed by the FAA-approved overhaul manual. This varies from shop to shop and overhaul to overhaul, so we weren’t able to form a clear picture of the precise difference between a P&WC factory overhaul and a competing field overhaul.

Dealers we spoke to seem to have a clear preference for factory overhauls and for one reason: sustaining resale value. “We only go with factory overhauls. And the reason for that is that it removes a rejection on resale. It just takes it off the table,” says Banyan’s O’Keeffe. But this advice isn’t universal. An owner who is either buying a PT-6-powered aircraft or overhauling one he intends to keep indefinitely can save up to 20 percent by buying a non-factory overhaul. That isn’t a trivial sum. On a twin-engine aircraft, it could amount to $150,000. And any owner who expects to recoup the premium cost of a factory overhaul will likely be disappointed. “Unfortunately, especially on the upgrades, the consumer just doesn’t share the value assessment. So recouping all of his investment can be challenging,” says O’Keeffe.

Recommendations

PT-6s are simply too complex and the aircraft values too variable to make one-size-fits-all recommendations on overhauls. Without detailed knowledge of the various dash numbers, the service bulletin status and economics of potential upgrade paths, an owner will be swimming in a sea of unknowns when overhauling this class of turbine. The probability of making a costly error nearly equal to the value of the airframe is high.

We think the best approach for an owner considering a PT-6-powered aircraft is to engage a broker who’s a specialist in the model under consideration and to be wary of buying an airframe with runouts and a plan to overhaul the engines.

“If you buy an airplane and you do the engines, you’re gonna be stuck with it,” says Conrad Jones of Kansas Aircraft. “Otherwise, you’ll take a hit improving it for the next guy. What I tell people is the best place to buy an airplane is one that’s already been overhauled. An airplane with zero-time engines and one with 500-hour engines are worth virtually the same because the overhaul cost is so far in the future, nobody stops to consider it,” he adds. Indeed, with an overhaul 2000 hours into the future, many owners figure they’ll sell the airplane long before that.

Otherwise, for an owner approaching a PT-6 overhaul for the first time, we think retaining a service such as Specialty Turbine Services is hands down, the best way to go. STS’s Paul Jones told us the company averages about $5000 in fees to help select an overhaul source and see the engine through the process. Given the consequences of bad decision-making on a PT-6 overhaul, that’s a mere pittance.