Get a taste of water flying and we pretty much guarantee you’ll consider your own seaplane. Got a runway to put it on and a hangar to stuff it into? The venerable Lake Amphibian should be on the list for shopping. Yes, there are some modern alternatives in the experimental and LSA market, including the well-rounded Sea Rey.

Still, the Lake single-engine pusher has been a staple in the amphib world as far back as 1957, and while owners love them unconditionally, you’ll never hear boasts of impressive cruise speeds. Just the same, we know folks who travel in Lake amphibs and yes, they fly them IFR. These can be reliable go-places machines.

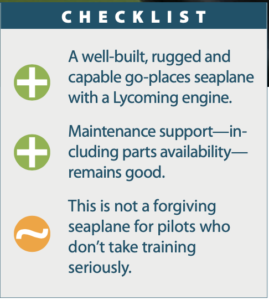

But don’t underestimate the challenges of maintaining an engine set way up in the air, and hard-nosed insurance requirements for serious initial and recurrent training, especially in the current hardened insurance market.

THE LITTLE FLYING BOAT

The Lake series was originally developed by Grumman, the maker of now classic multi-engine flying boats, as a potential entry in the civilian market after World War II. The company built a prototype but decided not to go any further, letting two of its engineers—Dave Thrust and Herb Lindblad—take the design, which Grumman called the Tadpole, and start building it in 1948 in Sanford, Maine, as the three-seat 150-HP Colonial C-1 Skimmer.

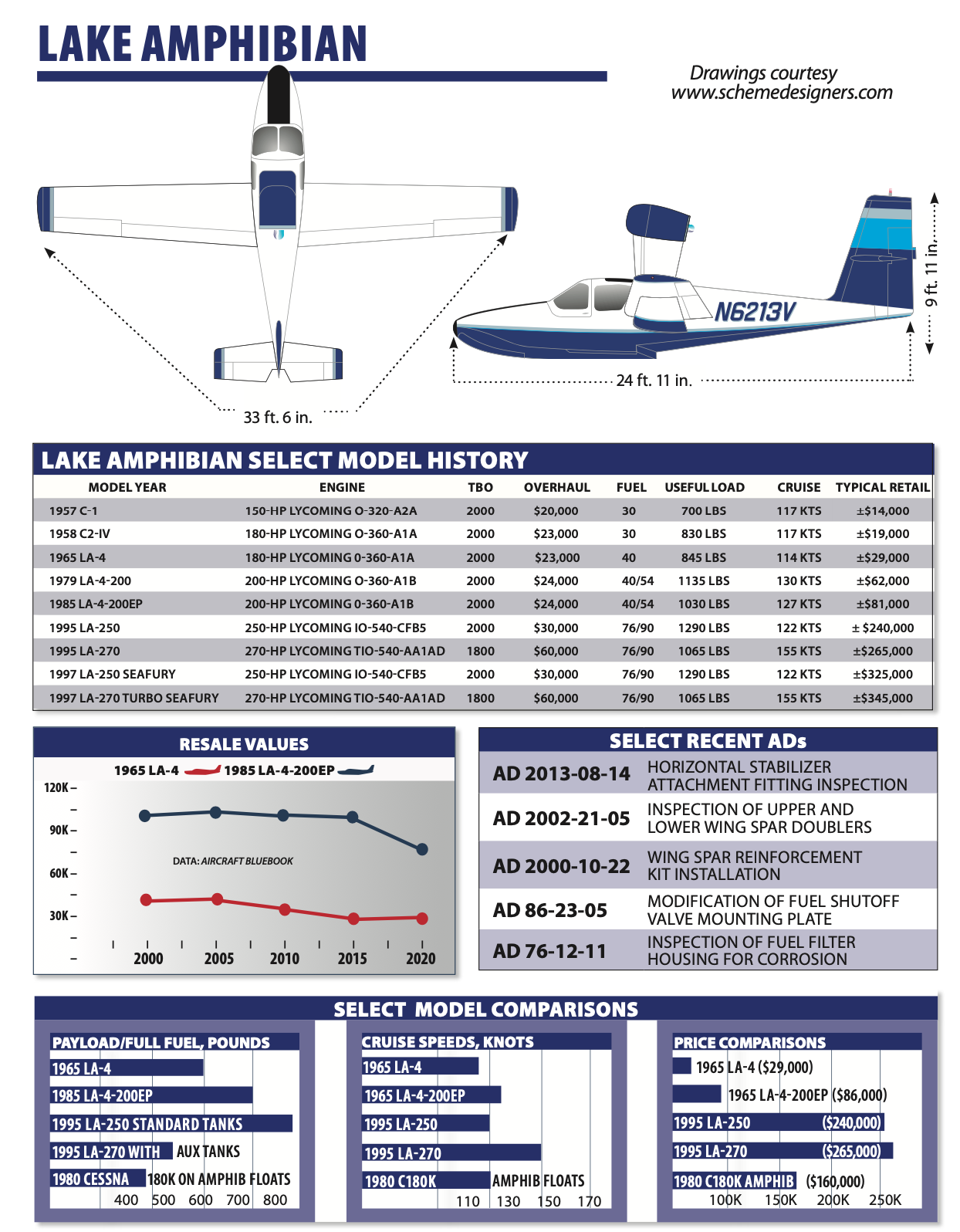

Flash forward ten years when they made it a four-seater with a 180-HP engine and called it the C-2. In 1960, they extended the bow and wings and dubbed it the Lake LA-4. About 250 Skimmers and LA-4s were built before production ended in 1962. There were some company changes that saw the manufacturing side become a separate entity, called Aerofab, from the sales and service side, an arrangement that continued until production stopped. The type certificate was acquired by Consolidated Aeronautics (Conaer) in 1963, which moved its corporate headquarters to Texas but kept the factory in Maine.

The Lake Buccaneer (LA-4-200) was born in 1970 when Conaer put a 200-HP fuel-injected Lycoming on the LA-4. Over the years, a few turbo models were made and at least one non-amphibian water-only model.

In 1979, Armand Rivard, an independent Lake distributor, bought the company and moved it to Kissimmee, Florida. He introduced the LA-4-200EP.

To reduce cooling drag and noise, it had a new nacelle and its prop shaft extended five inches farther aft. It also had “batwing” fillets at the wing/fuselage junction to improve low-speed handling by eliminating eddies and turbulence that disrupted prop performance.

Rivard also introduced the Renegade in 1979, a six-seat version with a 250-HP IO-540, a beefed-up structure, a rear cabin door and larger tail. It easily outperforms its predecessors and is even more stable on the water.

Beginning in 1981, the Lakes all got more grease fittings, polychromate primer, an improved canopy and more rust-resistant cabin vents.

A turbo version of the Renegade became available in the late 1980s through an STC, so technically it is a mod done by the factory. Its Lycoming TIO-540 is rated at 270 HP.

In 1991, the company started making the Seafury, a Renegade with lift rings, survival equipment, a custom tool kit, aux power receptacle and stainless steel brake discs, plus extra corrosion-proofing in an extra coat of chromate primer inside and out and a ceramic coating on the steel parts.

Finally, the company developed the Seawolf. It’s a Seafury modified for the military as a patrol, reconnaissance and special ops aircraft that has proved popular on the international market.

The company had a hiccup when Armand Rivard decided to try retirement. His son, Bruce, had no interest in taking over the factory so, in 2002, Armand sold his end to a Maryland FBO operator, Wadi Rahim, who called the company Global Amphibians and shut down the Maine factory.

Only two of its veterans moved to a new factory he opened in Florida, according to Bruce Rivard. Things did not work out and before long, his father got the company back. Bruce handled North American sales and service out of New Hampshire (go to www.teamlake.com), including finding good used Lakes and upgrading them for sale with a warranty. Production slowed to special orders only and, in the last few years, stopped.

Prices have a very wide range from $14,000 average retail for a good C-1 Skimmer (a pretty rare find; fewer than 25 were built) to nearly $350,000 for a 1997 LA-270 Turbo Seafury, according to the Aircraft Bluebook.

Moreover, prices have been stable, but as the market goes into a COVID-19 holding pattern, that might change. The 200EP is praised as the best compromise among Lakes between cost and performance. The Bluebook shows a 1983 LA-4-200EP at $75,000 average.

PERFORMANCE, HANDLING

“Instant vacation” is what one owner has called the Lake experience, and Lake fans say there is nothing else short of homebuilts and a couple of exotics (anybody know of a clean Seabee?) that lets them fly as easily into a remote lake or stretch of river as on or off a runway. Of course, Icon aircraft is trying to make these operations a reality for more people with its A5 LSA amphib. Still, as with most machines that float and fly, that flexibility comes at a price in cruise efficiency. For certain the Lake, for its power, does not go fast.

A 200-HP Buccaneer performs on a par with a 150-HP landplane—one owner said that he flight plans his Lake at the same speed he does an older Cessna 172. Owners reported that book cruise numbers were not realistic. They reported cruise speeds in the 105- to 115-knot range with fuel consumption of about 10 GPH. A Renegade cruises at about 122 knots and one owner told us he burns 13.5 to 14 GPH. The turbo version shines up high with cruise speeds closer to 150 knots. That’s pretty respectable, in our estimation.

The EP does better than the Buccaneer, cruising at about 120 knots. It has hull strakes that improve water handling and allow the hull to break free of the water at a lower speed—45 knots instead of 53 for a Buccaneer (50 knots with a batwing mod).

A Renegade pilot told us the EP is the best of the lot, is almost as fast as the Renegade, has better short-field performance and is more economical.

Company specs for the 250-HP Lake list cruise as 132 knots true at 6000 feet with 75 percent power with a 900-FPM best rate of climb at sea level. The turbo version, with its 270 HP, has the same performance except up high, where true airspeed is said to reach 155 knots. The EP’s best rate of climb is 980 FPM, according to company specs, and the Buccaneer’s rate is optimistically listed as 1200 FPM. An LA-4 with 180 HP is said by the book to climb at 1000 FPM.

Owners have complained that a heavily loaded Buccaneer (it can carry about 1000 pounds) is sluggish during climb. Some call it a two-place airplane with baggage or a four-place airplane with reduced fuel and bags. Lake’s 180-HP models should be avoided by buyers looking to carry a lot. At gross weight, climb will be around 500 to 600 FPM and cruise will be about 105 knots, max.

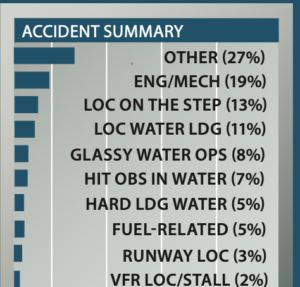

The Lake’s tendency to nose down when power is added and to rise when power is reduced because the engine is mounted high above the CG is one of the many reasons that a thorough initial checkout is in order, in our opinion. Owners reported that it’s wise to practice low-altitude go- arounds because of the nose-down pitch with power—one said, “Botch the power input on a bounced landing, while low and slow, and you’re going to break it—probably badly.” The high rate of accidents following bounced water landings we saw in the NTSB reports seemed to confirm this owner’s concern.

In flight, the airplane is agile by seaplane standards. The ailerons are light but the rudder is a bit heavy, and flying the Lake well requires good rudder skills in the air and on the water. Stalls occur just above 42 knots or so, indicated. Recovery is gentle and predictable.

Having a Lake is not so much about its cross-country flying abilities, which are fine for shorter flights up to 300 miles or so. It is all about getting yourself right into the countryside for whatever fun you have in mind. The airplane shines on the water, owners say, because its hull is inherently stable and strong and its CG is low. On a hot day, it takes precise technique to get a heavily loaded Lake on step for takeoff, especially the older models without hull strakes, available as a mod to reinforce the hull and reduce water drag. They also add more stability in turns.

Nevertheless, the airplane does not have a deep-V hull, as does a Seabee, so it does not handle rough water well. In addition, it is a short-bodied flying boat, making it at risk for porpoising. It is a descendant of the Grumman line of flying boats and shorter than the smallest of the marque, the Widgeon, which was not at all tolerant of errors in pitch attitude on landing—many Widgeons were lost to porpoising events.

The Lake accident records are loaded with water mishaps. Catching a sponson in the water landing in a gusty crosswind can cause an upset and a lot of damage. Bad landings or rough water can end with the Lake trying to play submarine. In anything but calm air, docking is a major challenge because the mid-level wing and its sponson may not clear the deck.

On the ground, the Lake pilot needs a knack for steering with differential braking because the plane does not have a steerable nosewheel.

It’s absolutely essential—and required for insurance coverage—to get Lake-specific training. The active and, in our opinion, effective Lake Amphibian Flyers Club can provide a list of highly qualified Lake CFIs (not to mention knowledgeable Lake shops, an absolute must for any prebuy evaluation).

Lake Aircraft’s Team Lake in Gilford, New Hampshire, offers a one-day introductory ground school that opens the new Lake owner’s eyes to what the airplane can do and what to be careful about, not the least of which is the lack of a gear-warning horn and the potential for landing gear up on a runway (not so bad) or gear down on the water (extremely bad). Also note there’s no squat switch to prevent a gear collapse on the ground if you accidentally flip up the gear switch. Lake also offers a five-day ground and dual course. Be prepared to work hard.

LOADING, COMFORT

Useful load in real life averages about 800 pounds for a 180-HP Lake without an IFR panel. It’s about 950 pounds for the 200-HP version and 1200 pounds for the Renegade.

Lakes tend to be nose heavy, a trait that is aggravated by the fact that the CG moves forward as the airplane is loaded. We’re told that a Lake EP, as one example, has a rear CG when empty and requires forward ballast when flying solo. Adding passengers eliminates the rearward CG, but can result in a forward CG and the need for aft ballast. The point to remember is the Lake is not a load-and-go airplane. Having the CG beyond limits for a gross-weight takeoff with a lot of pine trees beyond the beach is asking for trouble.

Only mods and the Renegade airframe have a back seat/cargo hatch, so expect to utter a few expletives when it’s time to get in all your fishing and camping gear through one of the two front clamshell doors.

Fuel capacities range from 30 gallons in the Skimmers and 40 gallons in the old LA-4s. The Buccaneer had a 55-gallon option and the Renegade carries 90. There’s a mod available for the older Lakes to put fuel in the sponsons, adding 14 gallons total.

There is elbow room up front, a bit less in the back. In older models, the hard seats adjust only fore and aft and the cabin is noisy. The EP model has more foam and customized features, and the Renegade has the nicest interior of all; its price reflects it.

There’s no muffler cuff ahead of the firewall to collect heat for the cabin. Through 1973, Lakes used Janitrol gasoline heaters, for which an AD required complete overhauls every two years. Lake switched to Southwind heaters in 1974, but they had only on and off switches so the choice was cook or freeze. Lake went back to improved Janitrols in 1983.

SYSTEMS, MAINTENANCE

For a complex airplane that performs in a tough environment, the Lake has amazingly few ADs.

Hydraulics are used extensively on the Lake, running trim, flaps and gear all through one accumulator, pump and reservoir. All the actuator static and dynamic seals are plain O-rings and the failure of one will incapacitate the whole system. “You may replenish the supply from your squirt bottle and position the gear, flaps and trim,” an owner told us, “but the flaps and trim will bleed to the trail positions.”

All seaplanes leak. It’s a fact of life. The hull of the Lake is broken into compartments with drains at the bottom of each—accessible when the airplane is on land. To purge the bilge water when on the water, there is an electric pump located near the step. So long as the airplane is sitting level, owners tell us that it will get rid of most of the water in about five minutes.

The problem comes if the airplane is parked, on its gear, in the water with the tail low (not unusual). The pump will not remove the water in the aft portion of the hull and can lead to an aft CG on takeoff. From owner feedback and a review of accident records, we think this has led to at least one accident. The bilge pump should be run after the airplane is sitting level in the water with the gear up.

A big issue, of course, is corrosion. During the 1960s, the 180-HP Lakes had no zinc chromate treatment and some didn’t have alodine. Check for a faint gold tint to the aluminum on the interior structure of any pre-1970s airplane. No tint, no alodine.

The absence of green zinc chromate primer makes the airplane susceptible to corrosion, especially if it flies into saltwater, and a bad case of corrosion can render a Lake worthless. Starting in the 1970s, all Buccaneers were alodined and zinc chromated; starting in 1983, an additional polychromate primer was applied.

Corrosion isn’t the only water worry. Lakes take a beating from waves and junk in the water that can lead to dings and dents. Gravel, rocks and sand strip paint and gouge the hull. Watch for it. Also check for internal damage at bulkhead station 97, a stress point for the hull. It was beefed up beginning with 1982 models.

There have been a few complaints about the turbo 270 model. Oil dripping from the crankcase breather tube makes a mess of the tail.

A search of Service Difficulty Reports going back a decade did not yield a lot of them. About a third involved cracks in structural components; there was no distinguishable pattern among the remainder. But at this point the majority of aircraft have been fixed. If the wing spar AD has been accomplished, it’s no longer a concern. Depending on the method used to comply with the tail AD, these can be one-time fixes with no recurring actions needed, or may need recurring inspections at annual, 50-hour or 850-hour intervals.

Owners were unanimous in telling us that having a prepurchase examination done by a shop that knows the ins and outs of Lakes is essential. One owner passed along his experience of taking his prospective purchase to a shop that had little Lake experience and that gave him a thumbs up on the airplane. He said that he bought the airplane for $80,000 and then spent $200,000 getting all of the undetected problems fixed.

MODS, OWNER GROUP

Bruce Rivard’s Team Lake in Gilford, New Hampshire, is praised for good service and accessibility. The company will help source a used Lake and even handle the transaction, including the prepurchase evaluation. It also has inventory of its own.

The bona fide Lake type club is the Lake Amphibian Club (www.lakeamphibclub.com), and it was formed by key members of the previous Lake Amphibian Club. The LAC renewed the traditional four-day fly-in and safety seminar (LakeFest) and publishes the Lake Club news.

Popular mods are wing fillets or “batwings” to smooth airflow into the pusher prop and improve low-speed performance. Vortex generators also make for better slow-speed handling.

There’s a “hydro-booster” kit to fit strakes on the hull to stiffen it and allow for easier water liftoffs. A cargo door is a boon for getting into the back seats and the cargo area. Adding hatch holders is a good idea and turning the sponsons into auxiliary tanks is another option. We highly recommend the LAC for guidance.

Our review of the 100 most recent Lake Amphibian accidents revealed amazingly few of the type of accidents we see in airplanes that cannot take off from water after landing on it. There were no gear-up land landings at all—and there were no reported times that the gear wouldn’t extend.

The absence of gear-up embarrassments caused us to wonder whether amphibian pilots become so attuned to making sure that the Firestones are where they should be because the penalty for getting it wrong on a water landing is—distressingly often—death.

There was one gear-down water landing accident. Fortunately, the solo pilot was able to get out from the submerged, inverted airplane.

The other excellent news was that there were only two VFR-into-IMC crashes and only two pilots lost control and hit something during a go-around. Both are well less than half the number we expect to see.

There were 19 reports of engine stoppages or power loss—eight of which could not be explained or duplicated afterward. The ones that could be explained were because of errors in maintenance or failure to conduct maintenance.

Once Lake pilots decided to get their airplanes wet, the accident picture changed.

A combination of rough water, big waves or boat wakes with a Lake scooting along on the step on takeoff, just after landing or while high-speed taxiing seemed to be a recipe for trouble. A number of accelerating Lakes were thrown into the air at below takeoff speed due to rough water and the pilot then stuck a wing into the water, porpoised or hit the water well nose down.

We have sometimes felt that making a turn while on the step has the equilibrium of a beach ball balanced on a pin. About a quarter of the on-the-step accidents involved making a turn and putting a wing into the water. In some cases the inconvenient arrival of a boat wake tipped the fragile step taxi balance equation, and the flying boat.

While there were only three runway loss of control (LOC) landings—we credit the wide gear—there were 13 water LOC landing events and five water landings hard enough to cause structural damage.

Seaplanes are intolerant of any amount of yaw on a water touchdown and the penalty is often that the airplane flips. The Lake is no exception. One pilot bounced twice and didn’t keep the airplane straight on the third touchdown. Another attempted what we consider to be one of the more challenging types of landings in a seaplane—crosswind on a river. He didn’t cancel out the yaw and, as with the previous example, flipped the airplane.

Glassy water presents its own set of challenges because the human eye cannot focus on the surface so it’s impossible to know precisely how high you are. Not surprisingly, it led to eight Lake crashes (although Lakes are no more susceptible than other seaplanes), one while the pilot was turning from base to final and hit the water. One pilot took off from calm water and then decided to fly low. At cruise speed he started a turn and put a wingtip into the water. The resulting cartwheel killed all aboard.

MARKET SCAN

Published Aircraft Bluebook average retail values are mostly unchanged since we looked at these aircraft a few years ago. Fetching the most money are late-model Lakes, of course. A 1997 LA-270 turbocharged Seafury has an average retail price of $365,000, according to Bluebook. Its Lycoming TIO-540-AA1AD engine has an average overhaul cost of $60,000 and an 1800-hour TBO.

A quick browse of the respected controller.com sales website revealed a few Lakes for sale. At the time we prepared this report (mid-April 2020)there was a 1989 LA-270 Renegade listed for $239,000. Always operated in fresh water, the airplane was used to set a 21,700-foot altitude record for light seaplanes. It had no damage history and a touch over 1000 hours on the airframe and engine since new, a fresh annual inspection and King Silver Crown avionics.

There was a 1986 LA-4/200EP Buccaneer for $134,900, with a fresh factory remanufactured engine and overhauled prop. It had an IFR panel with Garmin GNS 430W, a digital engine monitor, aux fuel tanks, cargo door, Vortex generators, a Hummingbird depth finder, Whelan wingtip strobes, plus updated leather seating. In our estimation, this is one of the better Buccaneers with a fair asking price.

Still out of the budget? We spotted a 1980 LA-4-200 with roughly 3000 hours on the airframe and 1000 on the engine since a major overhaul. It’s an IFR aircraft with a Garmin GNS 530W navigator, plus Vortex generators, aux fuel tank and an interior that was spiffed up back in 2007 and paint that dates back to 1992. It has an annual inspection due in August. The aircraft is priced at $69,900, but we’d budget more given the upcoming annual inspection.

We can’t stress enough the importance of conducting a thorough prepurchase evaluation by someone who knows these seaplanes well.

FIELD REPORTS

I have owned Lake amphibians for over 25 years. This includes a Buccaneer, an EP and my current Lake 250, which I have owned for more than 15 years.

I first soloed an aircraft on my 16th birthday and will be receiving my Wright Brothers master pilot award for 50 years of flying without an accident or incident in the near future.

I decided a long time ago that the Lake Amphibian was the aircraft for me. It is fun to fly, has great ramp appeal and can take you to places where no other aircraft can reasonably go.

I have the aircraft maintained by Amphibians Plus, with Harry and Christopher Shannon taking good care of our major maintenance including a recent engine overhaul, removing the vacuum system and installing the Garmin G5 and Aspen PFD.

Having an aircraft that can land at a cottage in northern Michigan or travel to a major airport for a business meeting is just fantastic. I may spend more than average maintaining my Lake 250 but feel the money is well spent for an aircraft that can make fantasy flights come true.

Trips to Alaska and the Bahamas are on the agenda, as well as attending the regular Lake Amphibian fly-in events, especially the event at Killarney, Ontario, which is a wonderful gathering of Lake Amphibians and the interesting people who fly them.

The Lake Flyers Club is a good source of information for anyone operating or thinking about purchasing a Lake Amphibian. I could go on with much more, but it looks like it’s a nice day and the water is getting soft this spring here in Michigan. I think I’ll go fly my Lake Amphibian.

Clifford Maine – via email

The Lake has been a big part of my life (46 years and counting) and I got my private ticket in a Lake Buccaneer back in 1974. I still enjoy the airplane and fly as much as I can. It’s more for fun now, but I do mix business with pleasure.

Team Lake in Gilford, New Hampshire, is very active in the top-end of the used Lake market and our company is available to assist with finding the best airplane for anyone interested in water flying.

For over 45 years Team Lake has watched and studied the used Lake market, which is shrinking as more Lake amphibians are exported and end up in remote parts of the world and seem to disappear.

Recently I visited with a couple of Lake owners from remote locations—one from Africa and another from Australia (the real outback)— and they both had the same thing to say about their Lakes.

“You must not be flying much, I haven’t heard from you in a long time,” I said. The response? “I use the heck out of it, and it just keeps on going,” was the answer. That’s an accurate testimonial for a good, well-maintained Lake.

We work hard to assist buyers in every aspect of Lake ownership, including flight training and aircraft support. This includes working with the insurance company and conducting maintenance at our facility in New Hampshire.

As for parts supply, they still come directly from REVO in Kissimmee, Florida. It supplies parts direct as well as to service centers including Lake Central in Canada and Amphibians Plus in Florida. I think both do a great job maintaining the fleet.

Worth mentioning is that Armand Rivard is actively discussing the sale of the Lake type certificate and related assets.

I only wish I had new Lakes to sell, but maybe soon!

Bruce Rivard (Team Lake, LLC) – Gilford, New Hampshire