There aren’t any magic bullets for eliminating general aviation accidents—but I’ve just run across a dedicated, reasonably priced simulator training program that has a lot of potential for reducing the most common type of GA accident, runway loss of control (RLOC).

For some reason, pilots and owners are not very good at responding appropriately when given hard data on risks. Case in point: RLOC. The crash data for the last two years of Used Aircraft Guides in this magazine shows that 23.6 percent of the wrecks for nosewheel airplanes and 53.2 percent for tailwheel airplanes were RLOC events. The numbers are probably higher because many RLOC prangs don’t meet the damage or injury threshold (which is pretty high) to be a reportable.

The most effective way to prevent an RLOC crash is to take recurrent training—yet if there’s one thing a general aviation pilot won’t spend a dime on if he can help it, it’s recurrent training. However, there’s a high probability that same training-resistant pilot has already shelled out a couple thousand bucks for a traffic alerting device even though midair collisions account for less than one percent of accidents.

There have been all sorts of attempts to cut down the RLOC accident rate over the years, yet nothing has worked. Pilots seem to stubbornly insist on their right to ignore an obvious risk and go on wrecking airplanes.

Crosswind Concepts, Ltd.

About two months ago, I was introduced to a company called Crosswind Concepts, Ltd. at a local pilot safety meeting. Manager Taylor Albrecht gave a brief talk about a crosswind training simulator the company was using. My experience with flight simulators for crosswind training had been that they were OK, not great—even the newest.

I went into my simulator session with low expectations. I came out impressed. Short review: The Redbird Xwind simulator combined with the straight-forward “hour of ground instruction, hour in the box” training program by Crosswind Concepts, Ltd., should dramatically increase a pilot’s ability to evaluate and handle a gusty crosswind through approach, landing and rollout.

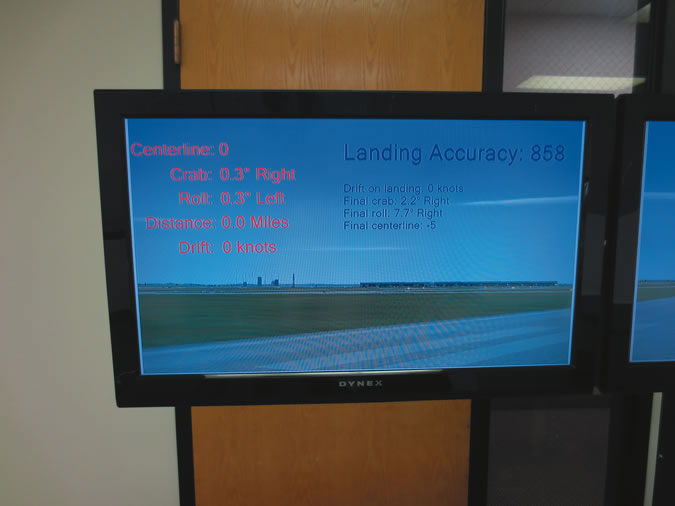

In addition, it provides an objective measurement of a pilot’s ability to land in a crosswind, scoring the approach, landing and rollout in their entirety and displaying the degree of yaw, amount of sideload and distance from centerline on touchdown. In my opinion, the objective data helps a pilot establish personal minimums for crosswinds far better than the current pass/fail system where after a landing you can either use the airplane again or you can’t.

The Simulator

Taylor Albrecht explained that the initial crosswind simulator was developed by Brad Whitsitt of Indianapolis. As it evolved, Whitsitt teamed with Redbird Flight Simulations to create the current version. It consists of an open cockpit with

yoke and rudder pedals. The cockpit moves left and right on rails as the pilot induces yaw—or doesn’t correct for wind drift—and rolls left and right at angles that are pretty close to the real thing when slipping for a landing in a crosswind. There is no pitch control—it’s not needed.

Three screens in front of the pilot present a convincing runway display. In the initial training mode (which a pilot can conduct without an instructor present, thus paying only for simulator time), the runway is endless, so the pilot can practice holding the airplane directly above the runway. He can internalize the idea of keeping the nose straight down the runway while correcting drift with bank and developing the muscle memory involved with making a wing-low landing in a crosswind.

In evaluation mode (an instructor must be present to run the sim), the computer sets the airplane up on final. The pilot then flies the sim all the way through the landing, seeking to touch down on the upwind gear, and hold it there with increasing aileron deflection during rollout as the airplane comes to a stop. The evaluation then appears on the screen.

In the Xwind Simulator, there are no distractions; it’s pure focus on crosswind landings. It continues as many times as the pilot wishes.

In the Box

I was told to start out by treating the simulator as an amusement park ride—to explore the controls while making coordinated turns as we’ll as side and forward slips. The computer screens were off.

Once the screens were turned on and I could see the runway, I relied on two stripes on top of the panel to determine whether I was yawing—and there was a constant readout of yaw on the left screen.

I found that the simulator was nicely sensitive in yaw; with a little experimenting, it would point the airplane very accurately and fairly quickly return it to a desired spot when displaced by turbulence or a gust.

The ailerons had a slight delay between cause and effect, and then reacted more than linearly. I felt that it was an attempt to duplicate the level of responsiveness of the ailerons when the airplane is slowed to approach speed. If so, I think the designers and tweakers got it very nearly right.

For me, confidence built rapidly as I flew it in a side slip above the runway centerline, dealing with crosswinds, gusts and turbulence of various magnitudes. The controls were effective enough to put the airplane where I wanted it; all I had to do was practice to get the modulation right.

Evaluation Mode

Albrecht then put the sim into evaluation mode and I started making landings—there was positive transfer from the flying over the runway exercise, making switching over to landing straightforward.

I liked that on rollout, it was necessary to progressively increase aileron deflection into the wind. If full aileron is not eventually used, the computer will dramatically pick up the upwind wing and cause the airplane to swerve. The steering feel changes as well; it simulates how the rudders behave as nosewheel steering becomes effective.

After coming to a stop, the computer scores the the full approach, landing and rollout, with 1000 being perfect. It also shows yaw, side load and distance in feet from centerline on touchdown.

Having the instructor make changes in the wind and turbulence variables during the approach required me to continuously evaluate what I had to do to keep the airplane where I wanted it and whether I was going to continue the approach or make a go-around.

I liked that the sim also showed the need for a pilot to make a correction as soon as the airplane wasn’t precisely where desired—don’t wait, act. My reaction was that this will be an effective tool for tailwheel pilots where delay in making a correction often means a groundloop.

The Training Program

Albrecht explained that the company was formed to provide effective stick and rudder crosswind training. It has two locations in the Denver area, with a simulator at Rocky Mountain Metro and Centennial Airports. Its training program has evolved into an hour of ground school and an hour in the simulator. Called Maximum Demonstrated Crosswind, the cost is $225. It is tailored for the customer’s level of experience and has proven to be effective enough that more time isn’t generally needed. Albrecht also organizes competitions within FBOs and is putting together some between pilots at different airports. The simulator costs just under $28,000.

Point Your Nose

The course starts with the concept of “Point your nose with your toes” for lining up the airplane—because the instructors have seen too much negative transfer from driving an automobile. It emphasizes aeronautical decision making and how to quickly evaluate a crosswind.

Crosswind Concepts, Ltd. has teamed with a large FBO—it requires its pre-solo students go through the MDC course. According to Albrecht, the FBO has seen the frequency of tire replacements drop as a result. Instructors who have canceled a lesson due to winds have sent their students through the MDC course so they can see what that flight would have been like.

The Xwind Simulator does not qualify as a simulator in which a pilot can log the time, which may be causing some resistance from student pilots. In addition, with the extraordinarily high flying time requirements under the new ATP rules, instructors who want to fly for the airlines are under pressure to fly every moment they can, and some are reluctant to put their students into a simulator because the instructor cannot log the time.

Albrecht is aggressively marketing the program and the sim as an effective teaching tool that instructors who want their students to be the best pilots possible should use. He is also reaching out to the FAA. Already at least one pilot who tore up an airplane in a crosswind and had to go through FAA-mandated remedial training has gone through the MDC course to comply.

Avemco Insurance likes the program—it’s giving pilots who complete the MDC course a five percent discount on their insurance.

Conclusion

In my view, this is a training device and program that can do a great deal to improve a pilot’s understanding of and ability to handle crosswinds in two hours.

For $225, it seems to me to be an inexpensive way to reduce the rate of the highest risk accident we face in general aviation, RLOC.