Years ago, the legendary Bob Hoover proved the 500-series Rockwell Shrike Commander’s nimble handling with an eye-widening airshow routine that will forever live on. But for more typical missions, the 500 Twin Commander rates high for owner satisfaction and dispatch reliability.

It’s simply a well-constructed and durable high-wing piston twin that doesn’t make blistering speed, but it’s fast enough to chew up the miles for personal and business travel.

Make no mistake, these are old aircraft with the same airframe concerns we have with the rest of the aging fleet. Corrosion, stress and overall supportability are things to consider when making the investment, but the owners we talked with are confident in their machines, and point out that there’s a lot to like about these old twins.

ANOTHER FROM TED SMITH

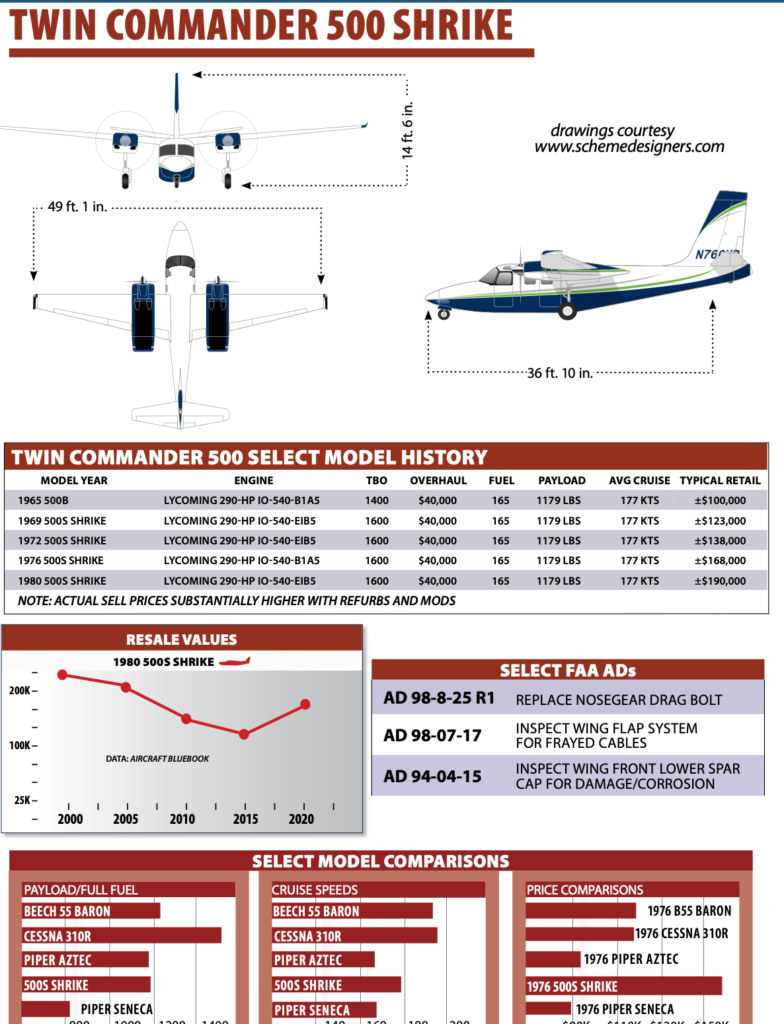

The Twin Commander as we know it was originally from the Aero Design and Engineering Company, later to become Aero Commander and then a division of Rockwell International. The first model 520 appeared way back in 1952, even before the Apache and the Cessna 310 introduced the idea of light twin ownership to the masses. If the Aero Commander looks vaguely like an Aerostar, there’s a reason. Like the Aerostar, the Commander is a Ted Smith creation, and has a signature Rockwell build quality.

The early 520 airplanes fell short in competing with the Cessna 310 and even the Piper Apache. First, at around $80,000 (big bucks back then) it was pricier than the Cessna twin, plus the small 260-HP GO-435 Lycomings weren’t exactly the best match for the hefty 6000-pound airframe. The unpressurized cabin and piston engines limited the 500S to a 15,000-foot ceiling.

The 500 Shrike had carbureted Lycomings that were a welcome relief from the pricey geared 295-HP GO-480s used on the Commander 560, which replaced the 500S and 520 models in 1954. Interestingly, the 560 model was the first light twin considered safe enough by the U.S. Air Force for use by the president. Later variants of the 560 featured more powerful engines, 32-inch wingtip extensions, hydraulics modifications, redesigned landing gear, fuel-injection engines and minor fuselage changes.

In 1960, there was major engine change, which switched the 500A from Lycoming to 260-HP fuel-injected Continental engines for a claimed 10-HP per side, both with a smaller displacement. Some will say the 500A is not nearly as quick in the air as the 500, despite the book figures that claim it performs better. We don’t really consider this airplane a light twin, and the early engine trials are proof.

But engine swaps were common back in this competitive time, and to run with the others, Rockwell brought the 500B. It had 290-HP Lycomings with three-blade props, the combination of which raised the gross weight by another 750 pounds to 6750. The 500B continued to 1965, when the 500U appeared. Presumably, the U stood for the utility category rating.

But everything changed for the Twin Commander around 1968 with the 500S Shrike model, which continued for nearly a decade. That means the newest 500S models (1980) are 40-year-old airplanes. The current Fall 2020 Aircraft Bluebook suggests a list price of $188,000 for one with current mods. But many owners have a lot more than that invested in their Shrikes. Many have been thoroughly and nicely refurbished, sizably boosting the value.

In the early 1970s, Bob Hoover’s popular Shrike airshow routine helped to boost sales, but sales ultimately tanked in the late 1970s bringing an end to the Rockwell piston twin.

Gulfstream continued to support the fleet until 1989 when the Twin Commander Aircraft subsidiary of Gulfstream was acquired by Precision Aerospace Corporation. In acquiring the company, Precision also acquired all of the type and production certificates, rights, tooling and drawings for all Twin Commander models ever produced. Precision completed the transition of the company from an OEM aircraft manufacturer to an OEM parts, service and support provider. The company was reincorporated as Twin Commander Aircraft LLC in 2003, and then acquired by James and Mark Matheson from Precision in a 2005 management buyout. In 2008, the Mathesons sold the company to Firstmark Corp. of Richmond, Virginia, a company with a long history of supporting legacy aircraft. To this day, Firstmark Corp. continues to operate Twin Commander Aircraft for parts and service, in cooperation with a worldwide factory-authorized service center network for maintaining the Commander fleet—both piston and turbine models.

SPEED AND HANDLING

It looks fast, but a 500 Shrike won’t keep up with turboprops or even some piston singles. Content owners shrug it off, claiming 150 to 155 knots true out of the small-engine 500s and anywhere from 160 to 180 knots from the 290-HP models at high-fuel-flow power settings.

A Beech Baron, Cessna 310 or an Aerostar will beat some Twin Commanders by a healthy 20 knots, not even breathing hard. Range is mediocre. With 156 gallons usable and burning 30 to 34 GPH, the 290 HP models will range out to 800 nautical miles in still air, without reserves. No need to worry about bladder capacity here. With a full load of fuel, don’t count on carrying more than two to three passengers, depending on the equipment load.

But what the airplane lacks in performance it makes up for with predictable, sturdy flying manners. “Thanks to the big rudder, it has great single-engine and slow-speed characteristics and excellent control response even at very low airspeeds. Fly it at 65 MPH and you still have plenty of response,” a pilot with a lot of 500 flying experience told us.

Back in the day, Aviation Consumer asked the late Bob Hoover if he could do the same airshow maneuvers in other twins such as a Baron or Cessna 310, or whether the Shrike had some exclusive qualities. Hoover stopped short of saying he couldn’t do the same maneuvers in the other aircraft, but he noted that the Shrike was stressed for more Gs (it can pull 4.4 Gs positive thanks to its utility category rating). But we were told that he actually finesses the Shrike through the sensational routine with low G loading, within a 2-G profile.

Pondering the matter a moment, Hoover volunteered one elusive Shrike quality none of the other aircraft possessed: It shows up—get this—at zero airspeed with full power in the vertical. Where most other aircraft have a tendency to torque in this position, said Hoover, the Shrike holds true because of the tail dihedral, and its ability to hold aileron effectiveness down to no speed at all.

Having the opportunity to once do some work on Hoover’s Shrike when it was in town for an airshow, we can attest that this was a mostly stock airplane, and not heavily modded as many assumed.

As owners will attest, the aircraft has surprisingly low stall speeds for a heavy a machine (59 knots dirty for the Shrike) and has good low-speed handling with a Vmc of 65 knots. This translates to some extra margin in slow-speed operations and the all critical engine-out scenario. Pilots consider the 500s to be good short-field airplanes.

On the ground, things are somewhat quirky. Due to the hydraulic nosewheel steering, pilots must learn to taxi and start the takeoff roll with judicious taps on the brakes to steer. That’s because the first portion of travel on the pedals works the nosewheel steering, and the remainder triggers the brakes.

LOADING IT

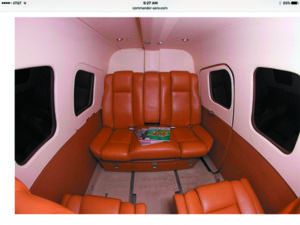

We consider the 500 Twin Commander a load hauler, and the cabin is as big as you’d expect. There’s no crawling around the seats as in a Cessna 310 or Piper Aztec. Depending on fuel loading, the airplane can accommodate seven people, including five in the rear passenger cabin. But, bring good headsets—it can be a noisy environment.

The high-wing design with engines right there out the passenger side windows has one notable drawback. Inside the cabin, there’s a high, resonant noise level that’s worse in the center seats alongside the propeller tips. Pulling the props back a bit helps, but that doesn’t do much for speed, which the Commanders aren’t overburdened with in the first place.

But you can load lots of stuff inside. Bring as many toys as you can fit, but don’t exceed the 350-pound limit in the rear baggage area. A generous CG envelope makes the aircraft almost impossible to load out of the envelope, and that’s why the Twin Commanders are popular with charter operators.

But you can load lots of stuff inside. Bring as many toys as you can fit, but don’t exceed the 350-pound limit in the rear baggage area. A generous CG envelope makes the aircraft almost impossible to load out of the envelope, and that’s why the Twin Commanders are popular with charter operators.

OPERATING IT

The Twin Commander has a simple fuel system, but we were surprised to find some fuel-related wrecks in our research. There are normally five fuel tanks—two in each wing, one in the overhead fuselage. Fuel feed is completely automatic so the pilot can’t really foul it up, as in other light twins. There’s no crossfeed either and just a single fuel gauge that gives a reading of the total fuel in all five tanks together. It has one idiosyncrasy, however.

The gauge peaks at 135 gallons and the needle won’t budge for almost an hour until the first 21 gallons—of the 156-gallon usable capacity—have been burned off. We say get a fuel totalizer, if not an electronic engine monitor with fuel-minding capabilities.

There’s only one fuel filler access for all five tanks, located on top of the inboard right wing. It pays to check the cap before flight. In one accident, the fuel cap chain was caught between the neck of the tank and the cap, and fuel siphoned from the tank, running it dry.

But be careful with this airplane when having it fueled. It’s easy for inexperienced ramp personnel to mistake it for a turboprop and pump in Jet-A. The piston and turbine Twin Commanders look alike, so supervise the fueling.

Among nonfatal accidents, by far the most grief involves landing gear problems, including gear collapses, inadvertent gear-up landings and inadvertent retraction while on the rollout. Although Commanders have a gear handle latch to prevent inadvertent retraction, no squat switch is provided to give an extra measure of security.

An FAA study of structural failure accidents between 1966 and 1975 showed that the Commander twins had the second worst record among 11 classes of twins, second only to the Piper Twin Comanche. And the accident numbers weren’t exactly low, either. See the sidebar to the left for our recent NTSB scan.

The FAA discovered that the stability of the original Commanders had a fatal weak link, a dangerous instability when loaded near the aft CG limit. No fewer than 22 cases of inflight structural failures were blamed on extreme pitch sensitivity at aft CG. But the problem was corrected in 1975 by Airworthiness Directive 75-12-9, which required installation of bob weights in the control system of all 500, A, B, U, S and other models. Buyers should double-check that this AD has been complied with. Since the AD, there have been few if any structural breakups that we can find.

Some models have only one hydraulic pump, on the left engine. Lose that on departure and you won’t be able to retract gear. Since only hydraulic pressure locks the gear in the up position, lose the engine and the pump and the gear will flop down when you can least afford the drag. That’s something to think about when departing a short runway with obstacles where engine-out performance is marginal, at best.

We looked back as far as 1995 trying to find 100 500-series Aero Commander (Rockwell) accidents. We found only 48 in the U.S. and 12 in other countries. While the fleet isn’t all that large, we still expected to find more mishaps.

We note that many 500-series Commanders are flown by Part 135 operators, which tends to reduce the accident rate. Nevertheless, we were intrigued, and our curiosity piqued, by what we considered to be a high number of accidents in other countries. While the existence of those accidents appears in the NTSB database, frustratingly, no details are provided.

A reputation for good ground handling among the fleet seems to be deserved; there were only two runway loss of control events, and one involved landing in a 15-knot quartering tailwind.

There were, however, four accidents attributed to the hydraulic braking system, all related in some way to maintenance—although one pilot launched knowing that the brakes weren’t working correctly. Yes, he went smoking off the end on landing. It appeared to us that all of those aircraft were on Part 135 certificates. We’ll say it again: Prospective buyers should never assume that an airplane has been well maintained because it was operated under Part 135.

Four pilots forgot to extend the Firestones prior to touchdown and three had the gear collapse after landing. One could not get the gear down and foolishly, in our opinion, shut down and feathered the props on approach. He stalled the airplane and hit so hard that there was major structural damage. Doh! “Hmm, let’s see, the gear won’t come down, that’s an emergency. It might be lonely, so I’ll create a companion emergency by shutting down both engines.”

The most frequent accident theme was fuel. There were 13 crunches; most involved running out of avgas. In a number of events the pilot departed with partial fuel and the fuel gauging system gave a false indication—one showing 65 gallons when it was empty.

It is not possible to determine fuel level by looking into the fuel filler when the system is less than full. (There were two accidents where the pilot thought the system was full of fuel but didn’t confirm by looking.) We think any potential operator of a Twin Commander should be especially cautious regarding the actual amount of fuel aboard prior to departure.

We also recommend training on the fuel system as two pilots inadvertently shut off the fuel inflight.

Watch the fuel type—two pilots tried to fly with jet fuel.

There were six engine failure events in which the pilot was unable to make a successful single-engine landing. One tried a single-engine go-around well over gross. It did not go well.

Four pilots stalled and lost control of the aircraft, one while intentionally practicing stalls at less than 1000 feet AGL.

The Commander line has a reputation for being structurally strong; however, everything has limits. Two pilots lost control in IMC, got into diving spirals and the airplanes broke up.

On the other side of the coin, we were impressed on reading the report of a pilot who took off in what he thought was good VFR weather at night. As he started his turnout from the airport, he flew into fog. He subsequently reported difficulty controlling the airplane, with bank, pitch and altitude excursions. At one point he heard a “pop.” He was able to climb out of the fog and continue to his destination, although the airplane required substantial right rudder and aileron. After landing he saw that the outer five feet of the left wing leading edge was “damaged with embedded tree debris.”

MAINTENANCE, SUPPORT

The good news is that Ted Smith built this plane to military standards, which means it is built like a tank. Moreover, Bob Hoover once told us he figured with all the rough treatment he dealt his Shrike engines—shutting them down when red hot—he anticipated they wouldn’t last 1000 hours. But his overhaul shop in California (Victor Aviation) told him they could have flown another 500 hours after the prescribed 1400-hour TBO.

Nevertheless, operators should keep up a healthy war chest for engine reserves since these motors will command about $50,000 a pop to overhaul. The Hartzell props seem to stand up well on the Commanders, too. Hoover volunteered that he marvels at how flawlessly they work, despite continuous feathering and unfeathering during his aerobatic routine.

Despite the handful of landing gear collapses we found, there were surprisingly few SDRs on gear problems. But we did catch several reports of cracked brackets, ribs and assorted flap-attach hardware blamed on presumably too-high flap-lowering speeds by pilots, suggesting that pilots overlook the max flap-lowering speeds (half flaps, 130 knots, full flaps only 118 knots) because of the high allowable Vlo limit of 156 knots.

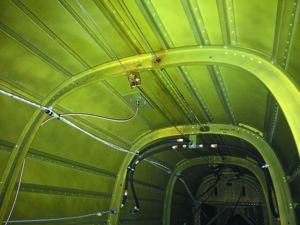

The horror story for Commander owners goes back to the mid-1990s when the airplane was saddled with a raft of ADs after corrosion was reported in the spar caps. The fixes are expensive and we recommend a thorough check of the records and the aircraft itself for compliance with them. By now, we’re hearing that most have been complied with. The worst-case scenario is bad beyond description and involves disassembly of the wing and replacement of the lower spar caps, a fix that could conceivably cost more than the value of an older airplane. More than a few have been scrapped by owners caught in the corrosion crunch.

Like most complex twins, we suggest budgeting big for annual inspections and unexpected repairs in between. Annuals that top $10,000 aren’t out of the ordinary. Owners and shops tell us progressive maintenance of some kind is the best way to keep this airplane in shape. This is not the airplane for owners looking to maintain it on the cheap.

The 500S has an expensive recurring (every three years) wing AD. Spar caps need to be checked for corrosion, which costs about $9000 to $11,000. If you have the lower spar cap replaced, then the AD does not apply.

Support from Twin Commander Aircraft (and its worldwide network of service centers) in Creedmoor, North Carolina (www.twincommander.com, 919-956-4300) remains excellent, we’re unanimously told by owners.

We talked with Andrew Wilson, the company’s Technical Service Manager, who said there will never be a lack of parts for the existing fleet of Twin Commanders, and the company is focused on bringing the aging fleet up to date, especially the 500S Shrike—the most popular and desired piston Twin Commander. There’s even a 24-hour AOG live support line. Parts are sold through the authorized service centers.

We asked Wilson about the realities of supporting these old airframes, but he said even techs at non-Twin Commander service centers can take the Twin Commander training courses.

As for those searching the used market for a Twin Commander and who concerned about the spar cap ADs, Wilson said you’d be hard pressed to find many if any airplanes that aren’t in compliance unless it’s been sitting for years and years. Plus it’s a repetitive inspection.

Wilson said there are a couple thousand piston Twin Commanders flying, and some have gone through the Renassaince Twin Commander program, which is a refurbishment process that can bring an airplane essentially to new standards.

“It’s a complete restroration to almost new condition where we zero-time the engines, new paint, interior, new avionics and essentially go through every part of the aircraft,” he said. As with most refurb projects, the Renaissance program brings the airplane up to a standard that’s similar to a new one rolling off the assembly line.

Pricing depends on the starting condition of the aircraft, of course, but million-dollar projects aren’t unheard of. There are three Renaissance centers that do the refurbs.

For added resources when it comes to support, upgrades and ops, there’s also the Twin Commander Owner’s Group online (www.twincommandergroup.com), and the Flight Levels Online forum (www.flightlevelsonline.com). We suggest all of them.

PRICE VARIATIONS

In addition to hitting the current Aircraft Bluebook, we did a current market search and found prices all over the board. At press time there was a 1974 500 Shrike for sale at a whopping $359,000. It had 3100 hours total time, with just under 500 hours SMOH on the Lycoming IO-540s and fresh propellers. It still had round-gauge flight instruments and a mix of older Garmin avionics and S-TEC autopilot. Paint and the leather interior are left over from 2004, and the airplane has a Cool Air cabin air conditioning system, winglets, flap gap seals, TKS de-icing system and an extended baggage area.

Contrast that with a 1973 model for sale at $179,000, more in line with Bluebook’s suggested retail price. It’s a higher-time airframe (7600 hours) and one engine is a couple hundred hours away from the published 1600-hour TBO, while the other is 800 hours since a major. It has older Garmin avionics and mechanical flight instruments.

Early Shrikes (1970 model year, as example) have a Bluebook suggested retail of $118,000. Real early 560 models are booked at $35,000.

Worth mentioning is a Twin Commander 700. This rare bird is a pressurized low-wing piston twin with 340-HP Lycoming TIO-540R2AD engines. This airplane was the result of a joint effort between Rockwell International and the Japanese Fuji Heavy Industries and it first flew around 1975. Cruise speed for it is impressive—around 245 MPH—and it has an empty weight of 4700 pounds. An orphan? Pretty much. The Fuji/Rockwell deal ended in 1979.

OWNER FEEDBACK

I’ve been flying in Twin Commanders since I was a very young child. My father had many. I have approximately 7000 hours of flight time and of that roughly 2000 is in Twin Commanders. I’ve flown most models from the 520 all the way up to the Jet Commander 1121B, plus I have time in the Westwind.

I currently fly a 1976 500S Shrike that I have owned since 1998, and I just purchased a 1982 695A/1000 model. Over the years my 500S Shrike has been completely refurbished from nose to tail—overhauled engines and props, new paint, new interior, plus an all-new instrument panel and upgraded avionics. I have also installed almost all the STCs and mods available for the plane. Most can be purchased from Gary Gadberry with Aircenter Inc. in Chattanooga, Tennessee (www.aircenterinc.com), which also sells Commanders.

The total cost to get my Shrike Commander to its current condition was over $200,000. My family and I use the Shrike for most of our domestic trips, business and personal. My daughter, a new private pilot at 17 years old, is learning to fly the Shrike and already has her eyes on the 1000, which I plan to keep along with my Shrike. (You tend to grow a fondness with the plane and personal attachment.) They just fly better than any twin out there. They are safe, rugged, have simple systems and look cool as hell.

My typical flight profile consists of four adults and their bags on a 500-NM trip. In cruise flight between 7000 and 9000 feet we see roughly 174 knots on 30 GPH. Total fuel capacity is 156 gallons and I take off with approximately 130 gallons for the trip. Others flying the 500A and 500B airplanes generally report 25 to 29 GPH total.

Annual inspections might start at around $5000 for a well-maintained airplane, but expect to pay a lot more, depending on the pedigree of the airplane.

Here are some bullet points that I think are worth mentioning.

• It’s nearly impossible to run out of fuel. All fuel feeds from a center sump tank that feeds the engines. No crossfeed. You either have fuel or you don’t.

• Simplistic landing gear system. The nosegear is held up by hydraulic pressure. Lose hydraulics and the nosegear will freefall. The procedure to extend the landing gear in an emergency is put the landing gear handle down—the plane does the rest. No cranks or chains. It’s the only plane in its class that you can visually check the landing gear position. Watch the mains out the window and the nosegear in the reflection of the spinners.

• Robust main landing gears. The mains are the same as the Turbo Commanders. They are rated for almost twice the weight of the plane. You’ll be hard pressed to find a main landing gear that broke—I don’t know of any events on the piston line.

• In the event of a belly landing, you can slide it in without incurring a prop strike because the high props will not strike the ground when the fuselage is sitting on its belly.

• Superior visibility. The engines and props are behind the cockpit. With the eyebrow windows on the Shrike, you will almost always have sight of the runway in a turn. You can’t really say that about any other plane, except the Ted Smith-designed Aerostar.

• Shrikes or those converted have separate entrances for passengers and pilots.

• The high-wing design allows for great passenger visibility of the ground while on trips in the airplane.

• Big cabin. The back seats slide forward and almost makes a very comfy bed for two when up against the aft-facing seats.

• It’s incredibly stable to fly and easy to shoot approaches and great in turbulence.

• It’s one of the best supported legacy aircraft. Parts are available through Twin Commander. Some are pricey, but at least they are still available.

• The airplane has awesome ramp appeal, it makes for an easy transition to higher-performing Twin Commanders and there is great support and comradery from others who own and fly them.

John Papageorge – via email