It used to be that equipping for legal instrument flight meant buying radios with glideslope and adding pitot heat. And while the equipment requirements in the FARs have changed little over the years, the technology sure has. These days entry-level EFIS and GPS navigators come well-equipped and approved for IFR, and even if you don’t actually plan to fly IFR, the equipment you bought is up to the task. In some ways, that makes the buying decision easier.

On the other hand, the market for retrofit EFIS and GPS navigators is crowded, and it’s easy to over-equip (which means overspending) for basic IFR flying. In this report we’ll backstop the buying decision and focus on the latest entry-level gear you might use for instrument training, light IFR, flying GPS approaches and as a bonus, also adding a healthy dose of digital reliability to an aging analog panel. The goal is to keep the total buy-in to a realistic $15,000 price point. (We’ll never say avionics upgrades are cheap, but they may be cheaper than ever before

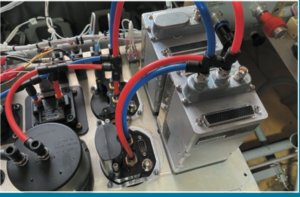

One of the goals with any modern avionics upgrade—especially in aircraft with avionics that haven’t been touched in years—is tidying up the space behind the instrument panel. Any avionics tech will agree that time and money spent to do that now will save time when they have to get back in to the suite to add wiring and components as the interface potential matures. From a cleanup standpoint, nothing frees up space more than removing the vacuum system, and that’s just what you can do with any of the budget EFIS systems we cover in this article. The photo in the upper right is the vacuum plumbing removed from a Lycoming O-360, which shedded nearly 15 pounds from the aircraft including the instruments and the pump. The other photo to the left shows the chassis of these new instruments. Moving from right to left, the larger ones are Garmin G5s, the ones in the middle are Garmin GI 275s and to the far left is a mechanical airspeed indicator and uAvionix AV-20. The blue and red tubes plumbed in are pitot/static lines.

SMALL SCREEN EFIS

Since the goal is a utilitarian, money-saving approach, settle on smaller displays. As appealing as a big-screen EFIS retrofit may be, it won’t be low budget or easy to retrofit because of the metal work that’s required to fit the display. But several entry-level EFIS models tame that dragon with a form factor that slides into the existing round-gauges cutouts. Let’s start with Aspen Avionics, a company that pioneered the idea of a no-cut EFIS upgrade.

The budget-priced Aspen EFIS is the Evolution E5, which trickles down from the company’s flagship Evolution Max system. While it’s de-featured to save money, it still comes with Aspen’s new and improved display technology that’s years ahead of the original Evolution display. It’s brighter, the onscreen data is easier to read and it has more failsafe backup.

Aspen was able to bring the price of the E5 down to $4995 (compared to $9995 for the flagship Evolution 1000) by sidestepping the TSO process in favor of an STC with approved model list (AML-STC), which is a blanket installation approval for hundreds of aircraft models. That STC, when installed per the manual, also includes the green light for removing the aircraft’s vacuum system—a popular trend for obvious reasons.

But this isn’t an all-glass makeover. An E5 installation means you’ll retain the airspeed indicator, altimeter and turn and bank instruments, while the E5 instrument will occupy the 3-inch attitude and DG instrument holes. The E5 (like all of the Aspen displays) is one self-contained instrument that can be installed in most panels without cutting or modifying the metal. But installation won’t be a while-you-wait affair. It requires the installation of a remote sensor module (RSM), which is an external heading and position sensor that’s mounted much like a GPS antenna on top of the airframe.

The E5 is intended for basic IFR panels and as standard it won’t have autopilot interface without buying Aspen’s optional ACU, which is an analog converter unit that converts the autopilot’s signal inputs to a digital format. This will add $1000 to the price, not counting installation. This component is included in the Evolution 1000 Max because that model was designed for more advanced interfaces.

The E5, on the other hand, is intended to interface with a single GPS navigator over its digital databus. Maybe a legacy Garmin GNS 430W/530W or any of Garmin’s current navigators, plus Avidyne’s IFD series navigators. For connecting analog VHF nav radios and multiple GPS navigators, you’ll need the optional ACU for the signal converting.

What we like best about the E5 is the added failsafe in case of a compromised pitot source input—something that’s been a weak link in previous Aspen systems. Like most EFIS models, the Aspen requires pitot static air input for the flight instruments and if the pitot tube is iced or clogged, the E5 reverts to GPS assist mode from the connected navigator. This displays the GPS groundspeed (instead of indicated airspeed) and warns you to turn on the pitot heat, while the attitude data still stays alive instead of flagging like it does without GPS assist.

Like the high-end Evolution, the E5 has a one-hour backup battery in case the electrics go down. The feature set is bare bones; there’s no touchscreen or synthetic vision. The E5 screen is divided into three parts: an upper attitude display, a lower navigation display and a data bar between the upper and lower halves. Unlike other Aspen displays, the E5 only has one page, so you’ll always view attitude and heading data, and of course EHSI when connected to an external navigator—something the E5 didn’t have when it was released last year. An E5 can be upgraded to a full-featured Evolution 1000, and you can still use the installed RSM and some of the existing wiring when upgrading.

GARMIN G5

We’ve covered the popular Garmin G5 in great length in previous articles so we’ll review the basics here. Sized to fit a 3 1/8-inch instrument cutout and sporting a 3.5-inch QVGA color LCD display (no touchscreen or synthetic vision), the G5 can be purchased as a primary attitude indicator and also paired with a second G5, which is a digital DG/EHSI that works with the GMU 11 external magnetometer for magnetic heading display. Without the magnetometer, you’ll see GPS track. When two G5s are paired together, the G5 DG/EHSI works as a reversionary attitude indicator if the primary G5 goes down. Both instruments have four-hour backup batteries.

The G5 DG is equipped for instrument approaches with its electronic HSI, but is limited to VHF nav and GPS sources with digital databuses, mainly Garmin GNS 430W/530W, GTN 650/750 and Avidyne IFD navigators. The G5 can also work with Garmin’s discontinued SL30 navcomm and the current GNC 255 digital navcomm through an RS-232 serial interface. See the sidebar on the next page for more on interfacing VHF radios.

If you have a third-party autopilot (we’re talking about S-TEC, BendixKing and even Century and ARC/Cessna models) the G5 EHSI can provide heading command with the GAD 29B converter.

Like Aspen’s E5, the G5 is utilitarian, but displays all of the flight data you’ll need for flying IFR and the STC allows for removal of the aircraft’s vacuum system. There’s airspeed, attitude, altitude, vertical speed, slip/skid, turn rate, configurable V-speed references and altitude select (for reference or for interface with Garmin’s GFC 500 autopilot).

To comply with the STC, even a dual G5 setup can’t replace the entire six-pack of flight instruments. They’ll replace the AI, DG or the DG attitude instrument can replace the rate of turn instrument.

The G5 is an integral component of Garmin’s GFC 500 autopilot because it provides pitch and roll outputs to drive it, while also displaying autopilot mode annunciation and flight director command bars. It has a basic altitude select and alerting feature that’s useful for IFR flying. For instance, when passing within 1000 and again at 200 feet of a selected altitude, the set altitude value flashes for five seconds. Bust the altitude by 200 feet and the selected altitude data box changes to yellow text against a black background. It’s a good backstop for keeping you honest.

The base G5 AI is $2299; the G5 DG/EHSI is $2599 and $3125 with the GAD 29B converter. All in, a dual G5 installation might run around $7000, maybe less, maybe more depending on the panel.

GARMIN GI 275

A suite of digital GI 275 flight instruments might not yield an entry-level upgrade—Garmin still purposes the non-TSO G5 for that. But with a form factor that directly replaces most 3 1/8-inch round instruments, the product could make sense for incremental upgrades.

The GI 275 series are independent multi-function instruments that have TSO and STC certification, a 2.69-inch diameter (active screen size) color capacitive touchscreen and an extremely flexible electrical interface potential. They can function as a primary flight instrument, EHSI, CDI, an MFD with synthetic vision, traffic and terrain display and an engine monitor. Let’s break it down, starting with the $3195 GI 275 Base model.

In the most basic form, a GI 275 can solve a dilemma faced by many when upgrading to an IFR GPS, which requires an external CDI because it works with a variety of GPS navigators that require an OBS course resolver—including legacy GNS 430/530 navigators. BendixKing KLN-series navigators also require an OBS resolver, but Garmin told us it doesn’t recognize this interface even though it might work. The instrument can accept and switch dual GPS inputs and dual VHF nav inputs for localizer and glideslope display. It can also be toggled as an MFD.

A step up is the $3995 GI 275 ADAHRS, which is the one for use as a primary and standalone EFIS because it has the sensors for displaying all primary flight data. When used as such, however, it’s locked to display only the flight data—no MFD. Synthetic vision is a $995 option and is downloadable, so you don’t have to bring it to a Garmin dealer for installation should you add it later.

As second GI 275 ADAHRS can be installed to replace a round-gauge directional gyro and it connects with an optional GMU 11 magnetometer for heading resolution. It can be configured as an EHSI, works with a variety of third-party nav sources and has mapping, traffic and weather overlay. A GI 275 ADAHRS with the magnetometer is priced at $4295.

One benefit of dual GI 275 ADAHRS units is failsafe redundancy. If the primary AI goes down, the one functioning as an EHSI reverts to primary flight data. The instruments have backup batteries and the STC allows for removing the vacuum system in this configuration. When used an EHSI, the GI 275 ADAHRS is locked, but also displays mapping.

For providing pitch and roll reference for driving attitude-based autopilots, the $4995 GI 275 ADAHRS+AP is the version you’ll want. There’s also an interface where a GI 275 can function as an engine monitoring system.

We’ve installed the GI 275 in our test aircraft and are preparing a full inflight performance report in an upcoming issue of Aviation Consumer.

Face it, the latest budget navigators from Garmin, and even used legacy ones, have all but made the traditional navcomm radio extinct. But that doesn’t mean you can’t save some money by interfacing one with a budget EFIS. For IFR flying (and training) you’ll need glideslope approach capability and you can get just that with a properly equipped navcomm. Garmin offers the GNC 255, upper right, and it interfaces nicely with both the GI 275 and G5 EHSI shown at the left. But at $4495, we think any of Garmin’s budget navigators makes better long-term sense if you can live without VOR and ILS in favor of WAAS GPS. Many can, especially for training.

You can cut the cost in half by scoring a used BendixKing KX155 (around $2000 for a good one), shown in the middle, but you need a good eye when shopping. Some versions don’t have glideslope and all are voltage specific—14 or 28 volts. The analog radio will work with Garmin’s new GI 275, but not with the G5 since it doesn’t have analog inputs. Perhaps the most versatile of all is a used Garmin-AT SL30, shown at the bottom. It has RS-232 serial output and works with the GI 275, G5 and Garmin’s GI 106 series mechanical indicators. The SL30 sells for around $2500, is a good performer and could be an interim money-saver for IFR equipage.

BUDGET IFR NAVIGATORS

No matter which small-screen EFIS you choose, we think the interface is complimented by a WAAS GPS navigator. For WAAS on a budget, Garmin’s new line of navigators—which aren’t equipped with VHF nav receivers—make good sense. But the choice isn’t necessarily easy. We covered the units in the navigator market scan article in the September 2019 issue of Aviation Consumer and determined that the GNC 355 was a winner, but not exactly a slam dunk. There are sacrifices, and those include settling for relatively small screens (4.8 inches) compared to Garmin’s GTN-series navigators, while also doing without ground-based VHF nav capability.

To review, the base navigator is the $4995 GPS 175. It’s strictly a GPS, but it does have built-in wireless for connecting with smartphones and tablets running the Garmin Pilot app. At $6995, the GNC 355 adds a 10-watt comm radio, and at $7995, the GNX 375 has no comm, but instead a built-in ADS-B transponder.

All of these navigators work with Garmin’s G5, GI 275 and even with Aspen displays. They are approved for Class I/II aircraft weighing under 6000 pounds and are approved under a 700-model AML-STC.

How you choose will depend on how the panel is currently equipped. For many equipping for IFR, we think the GNC 255 will make the most sense because it has the comm radio. You may or may not be comfortable flying IFR with a single comm, so you might retain an existing radio or install a standalone comm, which could add around $2500 to the project.

If you aren’t comfortable with ditching VHF nav capabilities, you’ll have to install Garmin’s GTN 650 (priced at $11,995) or Avidyne’s IFD440, for $11,999.

There’s also a fairly lively market for used navigators, mainly Garmin GNS 430W and GNS 530W units. These are long out of production, of course, but they are still supported. We searched the market and found that good ones (with recent factory service and in good cosmetic condition) have high resale value. Plan on paying around $7000 for a GNS 430W (the W nomenclature is important because it means it has WAAS) and upward of $9000 for a larger-screen GNS 530W. The GNS 430W/530W have VHF navs, but older processors and older displays compared to newer navigators.

We suggest working closely with your shop before striking a deal on any used unit. You’ll need an installation kit, mounting tray, navigation datacard and GPS antenna, which might not be included. The shop will also have to include FAA Form 8130-3 airworthiness paperwork to support the installation.

THE BOTTOM LINE

At press time uAvionix was working toward certification of its AV-series flight instruments, including the full-size, 12-in-1 AV-30. This is a highly configurable digital instrument that fits in a 3 1/8-inch round panel cutout and has primary attitude, slip, directional, airspeed and angle-of-attack data, plus battery backup.

As we reported in the March 2020 issue of Aviation Consumer, the AV-30 and smaller AV-20 are also used to control the uAvionix tailBeaconX ADS-B transponder. But until it’s certified, the AV-series units can only be installed in experimentals. The AV-30-C (pending certified model) is currently priced at $1995. We’ll keep tabs on these products.

If your plans include removing the vacuum system and you’re struggling between a pair of Garmin G5s or a pair of Garmin GI 275s, our advice is to get a hard quote for both options. The GI 275, with its round form factor, can fit exactly as an old round gauge did. This means no modifying the Royalite plastic overlay on many panels (the G5 fits a round hole, but has a square bezel that will require either modifying the plastic or doing metal work and removing it). But a GI 275 suite, or at least two of them, will be pricier than dual G5s.

It’s possible that a Garmin GNC 355 GPS/comm ($6995) and dual Garmin G5 flight display ($4900) install could sneak out the door for around $15,000 in basic interfaces. Of course that doesn’t include an autopilot or a transponder/ADS-B system. In that case, you might substitute the transponder-equipped GNX 375 navigator for an additional $2000, but that doesn’t include a comm radio. Maybe you retain an existing radio, search the used market for a standalone comm or install a separate ADS-B solution. Dual GI 275s and a GPS 175 navigator is $13,285, which is substantially more than the same package with dual G5s by nearly $3500. But again, there could be some savings in the installation, and the map and overlay capability on the EHSI (which doesn’t exist on the G5) could be worth it.

One way to prioritize and save a lot is to take an incremental upgrade approach by simply installing one Garmin GI 275 Base model and interface it with a Garmin navigator as the primary indicator. Keep the traditional flight instruments and install a second GI 275 as your budget allows. That’s pretty much what Garmin intended, since the GI 275’s form factor doesn’t require cutting the instrument panel—wire them up and drop them in the hole.

Last, get a side-by-side demo of a GI 275 and G5. The decision might be easier when comparing them, as the GI 275 simply does more.