The term “product support” means different things to different people. For example, someone in the market to buy a new aircraft may worry about whether the local FBO has personnel trained to maintain it. Meanwhile, a renter pilot buying a new headset wonders what will happen if an earcup cracks five years from now. Both pilots may also be in the market for a handheld GPS: Will database updates for it still be available in a few years? 288 Perhaps because of the relatively high prices we pay for these and other products, theres often the expectation of manufacturers supporting them forever. And Jeppesen should continue offering custom database updates long after the memory space required outstrips that available in the hardware. Good luck with both. So, how long can we expect to receive a manufacturers support for their products? What factors into a manufacturers decision to discontinue support of a product? Are our expectations unrealistic? If so, why?

Obsolescent Mouse Traps

In the bargain of always pressing for better technology, we also have to accept some obsolescence. Put another way, better mousetraps come along. The problem that many aircraft owners and operators cant get their heads around is that the old stuff still does the job for which it was purchased, so the idea of junking a navcomm because of a failed circuit board-even if that board may be 30 years old-doesnt seem rational when the airplane its in is 50-something years old. After all, parts for the airplane are still available, why not the radio? Lycoming supports engines they made in the 1960s.

With electronics, however, its different. A poster-child example is the wildly popular-in-its-day Northstar M3 Approach GPS navigator. First available in 1996, production of the M3 Approach was discontinued long ago. But it was only last year when then-current parent company, CMC Electronics, ended support and the M3 became a doorstop.

CMC said in a March, 2008, notice that it “evaluated several technical alternatives to extend the life of the product and…determined there were no cost-effective solutions.” Solutions to what? Trying to squeeze 10 pounds of aeronautical data into a five-pound sack, thats what.

Another example is Garmin Internationals well-regarded GPSmap 396. This portable navigator, introduced in 2005, was the first such product to feature a color screen and datalinked weather information, including near-real-time NEXRAD weather radar imagery. Late in 2009-early November, to be exact-the company stopped producing and selling new 396s. Why?

According to Garmin spokesperson Jessica Myers, the companys decision to discontinue any product-portable or panel-mounted-“may include…parts availability, the introduction of new products that superseded an existing product and/or a decrease in overall sales volume that no longer supports continued production.” What Garmin is saying makes business sense for Garmin and, in this case, its clear to us that introduction of the aera portables led at least in part to the 396s demise. But is it a fair deal for the customer? It depends on how long the old product is supported. Although you cant buy a new 396 now, repair support for it will continue. “Garmins objective,” Myers told us, “is to support all aviation products with repair services for the longest period possible. The standard objective is a minimum of seven years for panel-mounted avionics after the last date of production.”

According to Myers, Garmin intends to support the 396 for at least that seven-year period. She points out the company has been able to exceed that objective significantly, and “only recently discontinued service for our oldest panel mounts, which had gone out of production over 10 years ago.”

288

What about database updates for the 396? Scott Reagan, Jeppesens director of OEM Client Management, told us, “As long as we have a means to supply databases, we will do so.” In the case of the 396 and other versions of the companys portables, Jeppesen runs so-called “packing” software owned and supplied by Garmin against its own proprietary data. The results are what gets loaded into the device as a database update.

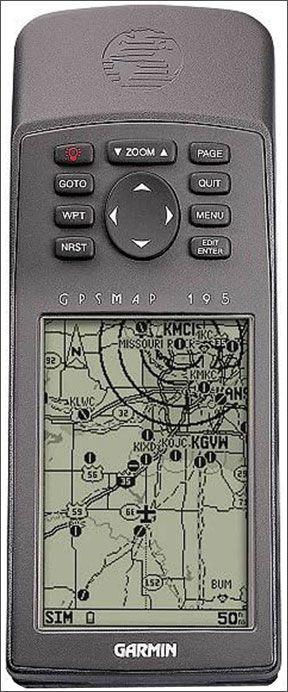

The trick is whether or not the hardware manufacturer-Garmin, in this case-decides it can no longer support the unit, Reagan told us. “The manufacturer decides whether to support the packing software,” which is the manufacturers property in the first place, he added. Think about another popular product, Garmins GPSmap 195. Its production was long ago discontinued, but Jeppesen still supplies database updates, even though the 195s memory capabilities arent the same as for other Garmin portables and, in fact, have been far outstripped by major improvements in hardware digital storage. “Memory capabilities can also dictate how long we can offer updates,” Myers added. Is there a threshold number of users below which its not economical for Jeppesen to supply database updates? Apparently not. According to Reagan, Jeppesen currently is “continuing support of several units for which we have less than a dozen subscribers. The OEM continues to support that packing software thus we continue to support the data services.” Thats analogous to Microsoft continuing to provide upgrades for people still using a TRS-80 from Radio Shack.

Which brings us back to the M3. It was designed at a time when large-volume digital memory was both rare and expensive. As a result, the M3 used a two-megabyte data card. A 2008 notice announcing discontinuation of database updates for the navigator notes, “Jeppesen databases have exceeded

288

these limits due to normal growth of aviation data. Furthermore, flash cards have become nearly obsolete and Jeppesen no longer has the parts necessary to build Skybound adapters for flash cards.” When manufacturers introduce new avionics, they fully realize that the components they use will eventually become unavailable. To provide a reasonable length of ongoing service, they purchase a supply of spares. But to keep products profitable, only so many spares can be stored.

When it designed and built the M3, Northstars use of a two-megabyte storage card was a business decision, probably based partly on then-current database sizes and partly on the technology available when it was designed. Since then, of course, things have changed. For one, more navigation fixes have been created thanks to the popularity of GPS approaches, stretching the M3s memory card beyond the breaking point. For another, moving map popularity-something the M3 never will be able to do-along with the unavailability of flash card components, made it obsolete.

Headsets

Some products are supportable almost forever. A call to David Clark revealed that an ancient passive headset with a broken volume knob is still repairable. “If we make it, we can repair it. Just send it in,” we were told. Thats likely to be less true with noise-canceling headsets, whose electronic components, like those found in GPS units, have a definite shelf life.

In 1989, Bose stunned the aviation world with its $1000 Aviation Headset, the industrys first noise-canceling product. But owners who thought a $1000 headset ought to last forever were just as stunned when Bose dropped support for the original headset in 2008, 13 years after production ended.

Boses Jon Previtera told us, “We had to stop offering repairs on our original aviation headset, Series I…due to the fact that we exhausted our supply of electronic parts and could not procure the old electronic components any longer. However, we continue to make available customer replaceable items such as microphones, cables and wear items such as ear cushions.”

288

LightSPEED, Boses chief competitor, is famous for its free repair service, yet even that can go on for only so long. The company has offered an innovative solution that others have tried, too: When a new model appears, LightSPEED offers a generous trade in on a new model. Even if the trade knocks the margin down, LightSPEED figures it had made a good investment in customer loyalty.

Its Just Business

Like it or not, companies like CMC, Garmin and Bose are in business to make a profit. That fact may be in stark contrast to the industry-centric altruism that many of us who own and operate personal aircraft expect the navigator we paid good money for 15 years ago to be fully capable until the last GPS satellite burns up on re-entry. The reality is that if companies cant make money or at least break even supporting legacy products, buyers shouldnt expect them to do so.

One avionics shop manager told us its ridiculous to think Garmin cant get displays for the GX-55 they inherited from Apollo but have now discontinued. “You can get anything you want made if youre willing to pay for it. Theyre just not willing to do that,” he said. But in the next breath, he added that he views this as a legitimate business decision based on cost control and the profit motive. It is, after all, why companies exist.

Garmins introduction of a new product line made the GPSmap 396 an unwanted competitor. As Garmins Jessica Myers put it, “Think of it in terms of your computer, camera, cellphone, MP3 player or any other consumer electronic item-a specific model number isnt usually manufactured for seven years. The capabilities exist in future models made by those consumer electronic manufacturers, but their older models are discontinued as newer products and capabilities are introduced.”

Another way of saying that is when a better mousetrap comes along, we all go out and buy one. As we use it, technology improvements march on. At some point, the best mousetrap you could find 10 years ago is eclipsed by a new all-composite, high-resolution mousetrap. Yet, our old mousetrap still does the job. Should we expect the mousetraps manufacturer to continue supplying the low-tech metal springs it requires, even if the rest of the industry has moved on to carbon-fiber

288

springs, which work much faster? Yes, for awhile. But not forever.

Supporting legacy products usually isnt a significant profit center for a manufacturer. Yes, theres the need for them to establish a reputation of providing support after the sale so customers will consider their newer products in a few years, especially in a market as small as general aviation. But its unrealistic to expect all companies to offer upgrades or even spare parts for ancient navigators, even if some still do. Buyers should go into the deal understanding this and although we might rail against it, it wont change the reality.

After all, the resources they will consume to keep alive that 15-year-old GPS would be better spent developing a new one, taking advantage of all the technical advances since then. And wed be better off buying the newer, more-advanced product: Well get better performance from it while rewarding the company for its innovation and for continuing to develop new products focused on our market.

Regardless, eventually that whiz-bang box in your panel or strapped to your yoke will be obsolete and unsupported, just as it is with eight-track tapes and the A-N radio range. As Jeppesens Scott Reagan put it, “This is one of the things like death and taxes. You know its coming and neither are welcome.”