In a world of pulling mags at 500 hours and turbos that last 1000, fuel pumps are a breath of reliability fresh air. So reliable, in fact, that it’s much more common for a pilot to have an engine stoppage because the pilot does not know the aircraft’s fuel system or misuses the boost/aux pump than because a pump fails.

Pumps for moving liquids have been around for centuries, so one would expect the design and manufacture of such relatively simple devices to have been sorted out.

While most engine-driven fuel pumps are rotary pumps, just like vacuum pumps, the vanes are metal, rather than graphite, so there’s no expectation that they will come to pieces every 800 hours or so. Diaphragm fuel pumps are equally reliable.

IS THERE A PUMP?

Whether you have to even be concerned about fuel pumps depends on the type of airplane you fly. The whole idea behind a fuel pump is to either get fuel to the engine or transfer fuel among tanks in the airplane. If you can’t transfer fuel in your airplane and it has a high wing and a carbureted engine, there’s no fuel pump—gravity gets the fuel to the engine. The fixed-gear Cessna Cardinal is an exception due to its wing/engine geometry and FAA certification requirements.

If you are flying a low-wing airplane or one with a fuel-injected engine, it will have an engine-driven fuel pump and a boost or aux pump. (I’ll use aux and boost interchangeably.) If the engine is carbureted, the aux pump is a backup should the engine-driven pump fail. If the engine is fuel injected, the aux pump is a backup and is also used to prime the engine for starting.

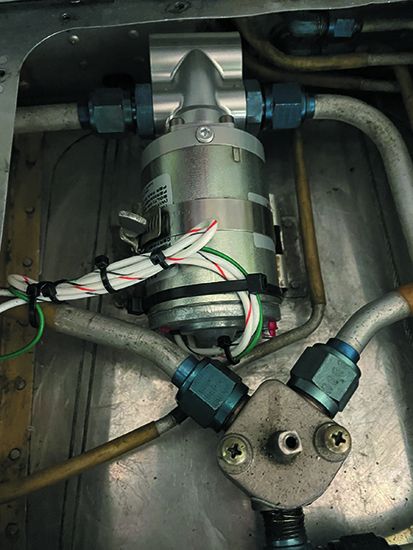

Per its name, an engine-driven fuel pump is attached to the engine and driven off the accessory case. A boost pump is electrically driven.

Depending on the airplane, it may not be possible to start the engine if the aux pump has failed.

EXPECTED LIFE

We were told by users, maintenance shops and overhaul facilities that engine-driven and aux pumps routinely last to engine TBO. The manufacturers call for overhaul at engine TBO or a calendar-year interval, usually 10 to 12 years.

The enemy of all fuel pumps is debris. According to Mark Mercer, chief inspector at Quality Aircraft Accessories, a major overhauler of fuel pumps, the failures he most often sees are due to debris that got into the fuel system when it was opened up to inspect or replace a component. He advised that any time the fuel system is opened up that it be flushed out before the aircraft is returned to service. In addition, the fuel screen should be inspected and cleaned at every annual. Debris that has been caught by the screen can eventually fragment and work its way through and into a pump.

Another bit of good news—fuel pumps don’t require preventive maintenance. What they do require is looking at them on a regular basis to check for leaks.

LEAKS

Boost pumps are made up of an electric motor, a pump and a space in between. If a seal or gasket wears out, the fuel is likely to leak into the space built to separate the fuel-containing part from the electric motor. That space has a drain—and it may have a tube that carries through the aircraft’s skin. Know where the boost pump(s) is on your airplane and where you would expect to see fuel if there is a leak.

If there’s a leak, don’t mess around: Replace the pump before further flight.

There are two symptoms of a boost pump starting to wear out that a pilot can detect. When priming, if the pump won’t generate normal fuel pressure, or it starts taking a longer time to do so, it’s a warning that the pump is getting tired. Second, if the sound of the pump changes, especially if there’s an unusual screech, a bearing may be going.

More and more owners are replacing or overhauling components on condition rather than time in service. Mike Busch, proprietor of Savvy Aircraft Maintenance Management, is an outspoken proponent of on-condition maintenance. In talking with him for this article, he was quick to caution that if an owner is going to go to on-condition maintenance for fuel pumps, he or she has to pay close attention to their condition. “They cannot ignore an odor of fuel when priming the engine. That’s a condition and it means taking action.”

IT’S BROKEN, NOW WHAT?

So the improbable has happened—your engine-driven fuel pump has a slow leak. You’ve had your A&P look at it and she’s told you in no uncertain terms not to fly the airplane. What are your options?

You can buy a new pump, buy an overhauled pump or send the broken one out for overhaul. For engine-driven fuel pumps, the price differential between new, overhaul-exchange and overhaul is often low, sometimes only a few hundred dollars. Your choices for a new pump will be limited to the manufacturer of the pump installed by the manufacturer of the airplane and approved as original equipment or another pump manufacturer that has received a PMA or STC for its pump on your type airplane.

There are several specialized shops approved to overhaul fuel pumps and suppliers such as Aircraft Spruce that sell new and overhaul-exchange pumps.

For boost pumps, the choice between overhaul and new is easy—there’s a big price delta, so plan on buying an overhaul-exchange unit if you’re in a hurry or having your pump overhauled if you’re not. Again, do a little price and manufacturer shopping as there may be more than one pump approved for your airplane.

Trying to keep track of how many companies manufacture fuel pumps isn’t easy. The rule of thumb is that the company that made the fuel pumps in your airplane will either still be in existence in some form (it may have a new name through merger or acquisition) or there is an overhaul shop that has approval to overhaul it.

If you want the lowest price and it’s OK for your airplane to be parked for about a week or so, you can send your pump out for overhaul by one of the specialized shops.

According to overhaulers and mechanics, an overhauled pump is essentially as good as new because all parts subject to wear are replaced. Following overhaul, each pump is flow tested and set to meet the manufacturer’s flow specs. Nevertheless, the flow will have to be fine-tuned to match the particular fuel system quirks and condition once the pump is on the airplane.

CONCLUSION

Both engine-driven and electric fuel pumps have a good record for reliability and need no preventive maintenance other than to keep debris out of the fuel system. If you are going to ignore the manufacturer’s recommendation on replacement/overhaul interval, then pay attention to warning signs that a pump is wearing out. If it’s leaking, don’t fly the airplane.