Let’s face it, compared to a Piper Cherokee or Cessna 152, many LSAs have complex systems and specialized parts. Imported models are often tainted by concerns of less-than-acceptable field support when they break.

Whether it’s dealing with composite structure damage, a failed Rotax engine or an emergency service bulletin, the efficiency of scheduled and unscheduled maintenance should be a sizable consideration in the buying decision. This includes parts support.

Several years ago while comparing the operating costs of a Cessna 152 and a Remos LSA for training, we concluded that the Cessna can be more profitable because, in part, replacement parts are generally more available.

That means less downtime—critical in a training environment—and less hassle (read buyer’s remorse) for recreational missions. As one LSA owner put it, “If I wanted a $180,000 hangar queen, I would have bought a vintage Ferrari.”

A more mature parts and support chain, we thought, could be convincing enough to spend serious money on an imported LSA. To find out what and how manufacturers are doing to improve upon the support of popular models, we talked with fleet operators, individual owners and visited with a couple of LSA distributors and service centers in the U.S. The takeaway? We see an improving support trend, likely the result of a maturing market.

Domestic advantage?

When it comes to LSAs, buying American is the ticket to great support, right? Not so fast. Remember, Cessna’s attempts at supporting its LSA—the Skycatcher—failed miserably, perhaps proving how difficult the task really is.

But indications show that sourcing parts domestically might get the aircraft off the maintenance floor more efficiently (and cheaply) than waiting for a parts container to arrive from Germany, as an example. Still, we found signs that skillful parts managers on the distributor level are better managing those logistics. More on that in a minute.

Helen Woods at Chesapeake Sport Pilot in Stevensville, Maryland, relies solely on an impressive variety of LSA models at her sport pilot school. With a flight line that includes a Van’s RV-12, a Tecnam P92, a Searey amphib and a Sky Arrow, plus prior experience operating other LSAs, including models from Flight Design and Remos, she told us Americanmade models have a much improved return-to-service record than the foreign models she has operated.

“I’m transitioning my fleet of LSAs to an all-American line. We’ve seen a major change in the past three years with second generation light sport models. With more American manufacturers—particularly kit manufacturers—I see the parts problem going away,” Woods told us. This also does good things for the bottom line.

“Not only can I readily get replacement parts, the parts are dirt cheap because some kit manufacturers have been building parts far longer than they have been building LSAs,” she noted. Chesapeake Sport Pilot has operated over 20,000 hours in LSAs and was one of the first LSA-only flight schools to dive into the niche market. It’s also one of the few survivors.

Woods has been so impressed with the service and parts support from Van’s Aircraft, she’s adding a second RV-12 SLSA to the fleet.

Big rocks, tall props

The upper end of the LSA market is becoming crowded with respected American LSAs, including models from Legend Aircraft, Cubcrafters, Van’s Aircraft and RANS Designs, to name a few.

John Whitish at Yakima, Washington-based Cubcrafters described the advantage of having a model line that includes both LSA (Carbon Cub SS and Sport Cub S2) and Part 23 certified (Top Cub) models.

“We were already we’ll conditioned before we even entered the LSA space. Almost every major component is built at our Washington location,” he told us.

Well, perhaps not every component, and that invites at least some parts logistic delays. Like many others, Cubcrafters sources systems like brakes, tires and wheels from outside vendors, including integrated avionics from Garmin and Dynon. On a side note, Cubcrafters isn’t the only manufacturer that’s seen impressive demand for Garmin’s G3X Touch integrated avionics. Like most other manufacturers, it will also offer Dynon’s capable Skyview suite, but notes that 85 percent of customers buy the Garmin G3X Touch over the Dynon SKyView panel.

Cubcrafters operates lean, but well-stocked, due to a diverse parts manufacturing line that feeds multiple products.

“Our parts department is responsible for supplying the line of production aircraft, our kit aircraft and also the source for all of the service parts,” Whitish said.

The kit aircraft he’s referring to is the $220,000 Carbon Cub FX Builder Assist model. As of June 2015, Cubcrafters has a fleet of 376 LSA models.

Not to say you can’t break one, but Cubcrafters could have a service advantage because of its rugged, backcountry-designed product. Whitish acknowledged the $184,000 Carbon Cub SS comes with relatively lightweight conventional landing gear, but offers a heavy-duty gear option. Still, Whitish doesn’t see landing gear prangs as being a real issue with its airplane’s owners. But if you do ball one up, Cubcrafters is growing the network of existing 28 service centers.

Import support

Most operators we spoke with gave Germany’s Flight Design acceptable marks for parts and maintenance/repair support. Much of that, in our estimation, has to do with a polished U.S. distributor infrastructure and a large fleet, compared to other foreign brands.

On the day we visited Flight Design USA’s Woodstock, Connecticut, headquarters we found an operation that was purposely configured for efficient around-the-country parts and in-service support. This included nearly $500,000 of on-hand replacement parts. It also has the ability to offer spares and in-house composite and propeller repair. Flight Design USA’s Tom Peghiny said support was a major focus from early on.

“Flight Design realized a long time ago that parts support is crucial to its fleet. If it was going to build a market in the U.S., it had to be able to support it. Part of that support effort allows us to build our inventory with factory consignment parts,” Peghiny told us. Since the distributor only pays for the parts it sells, this arrangement allows for well-stocked shelves for supporting not only its own service operation, but the other several distributors scattered around the country. It also eliminates the stress of tying up serious money in a parts inventory.

There are currently over 400 Flight Design models flying in the U.S. and over 1800 worldwide. In LSA numbers, that’s a sizable fleet and advantageous, in our view, for building a support network that stocks the most commonly used replacement parts. Unlike smaller brands that might only have a handful of aircraft in service, the existence of a larger fleet makes it easier for parts and service managers to know which parts are likely to fail—based on historical trends—and stock their inventory accordingly. But it’s far from perfect.

The ugly side of LSA upkeep is dealing with damaged landing gear components the result from runway mishaps, a trait that’s haunted the lightweight fleet almost since day one. In turn, savvy distributors keep a healthy supply of replacement landing gear struts and wheel fairings in inventory to help expedite the repair. It really comes down to customer service and preparedness.

“I understand that when a customer spends $180,000 on a new airplane, there is an expectation to have it back from service in a reasonable amount of time,” said Mat Fortin, Flight Design USA’s parts manager. That’s the support language we were looking for and saw evidence that Flight Design’s U.S. support infrastructure is on the right track—and expanding.

Distributors like Flight Design USA can also handle the general support of parts for other brands, particularly when it comes to composite component repairs and in-house support of Neuform composite propellers.

Shannon Yeager from Tecnam US in Sebring, Florida, reiterated that the new Florida sales and assembly facility is a direct investment by Italy-based Tecnam to better support its U.S. and Canadian customers.

“We have onhand nearly 80 percent of the service parts for all of our current products, both LSA and Part 23 aircraft. But I have to say with honesty that there has been some design changes from earlier models, so I can’t say that I have the entire legacy fleet covered all of the time,” Yeager told us. But Yeager also said that parts requiring special manufacturing might be sourced (from Italy) in around four days. This handoff from overseas is more than acceptable, in our estimation.

“Our location here in Sebring, Florida, puts us in better proximity to Miami, our inbound parts shipping location. The Sebring location is also where we distribute parts to service centers in Virginia, California and Minnesota,” Yeager said.

Interestingly, Yeager described an international shipping zone that’s in the works for the Sebring, Florida, facility that could prime the parts pump even more. Not having to pay customs fees until a part is sold can free up capital, while the operation stocks the shelves with more parts.

It’s worth noting that Tecnam once built fuselage parts for Airbus and McDonnell Douglas. As for aftermarket LSA support locations, Tecnam is slowly growing its national network, while being cautious about bringing on new service centers without properly training them. There are roughly 400 Tecnam LSAs in service. It’s currently waiting for Part 23 certification of its P2010 four-place single.

ENGINEERING HOLDS

It’s not only parts sourcing that can ground an LSA, especially for composite designs. Major repairs (guidelined by AMST standards) requiring repair instruction—essentially specific direction from the manufacturer on how to go about a repair—can delays the aircraft back to service.

For instance, should you drive your LSA into the pavement hard enough to cause structural damage that other aircraft in the fleet haven’t sustained (or that’s been repaired), the servicing shop can’t attempt the repair until the manufacturer engineers an official fix, or repair instruction. That’s where a larger fleet has an advantage, since there will be a larger archive of previously approved instructions.

On the other hand, factory engineering delays recently kept a Cirrus we use for product evaluations grounded while the factory engineered a fix for a delaminated fuel tank structure. Sometimes delays are unavoidable, no matter the size of the fleet or whether it’s an LSA or a traditional Part 23 aircraft.

When sourcing special order repair parts for imports (those not in stock in the U.S.), the common delivery timeframe we kept hearing during our research was “roughly three weeks.” But it could be much longer. Consider that Flight Design, as one example, first sources most major parts from Ukraine before the parts are sent to Germany for distribution to the U.S. and elsewhere.

Flight Design USA’s Peghiny noted that some parts could take several months before arriving at a distributor, although the customer might have the option of paying for expedited air freight. For large components, freight costs are huge.

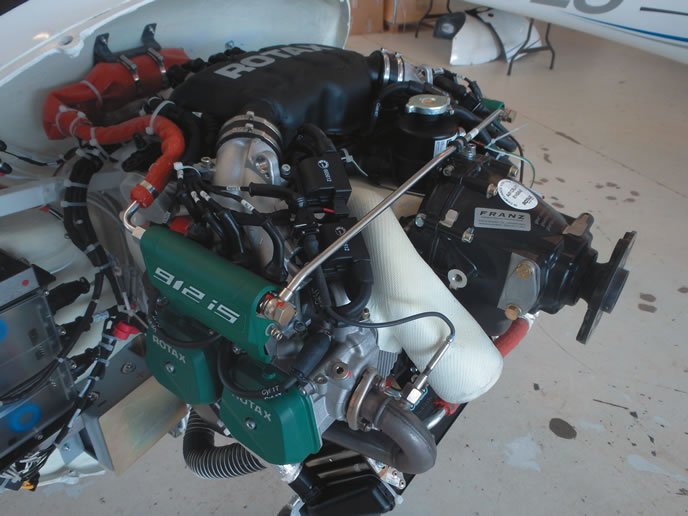

Rotax gushes and frowns

Owners and manufacturers generally have favorable things to say about Rotax, which has nearly 40,000 engines flying. You won’t hear about stuck valves, connecting rod failures, improperly seated rings and other issues that could plague what some naysayers might call “real” aircraft engines.

During our research, we did hear about issues involving Rotax charging systems, particularly in aircraft loaded with lots of current-drawing electronics. While there have been some efficiency gains through the use of LED lighting, for example, there is a worthy option for upgrading to an alternator to better handle larger loads.

If you’ve never operated a Rotax, expect some learning curve, and perhaps different maintenance issues than you might experience with a Lycoming or Continental. More than one distributor dinged the 912iS engine for nuisance LANE engine control unit (ECU) annunciations and other sensor-related quirks, but also admitted to at least some operator error when it comes to dealing with the Rotax ECU and ignition system.

“While it’s a strong and efficient performer, the realities of our customer experiences have been the disappointment with the still-evolving Rotax 912iS,” said one LSA distributor that wished not to be named. Instead, he favored the turbocharged 914 or 912ULS models.

Tecnam’s Yeager also favors the 115-HP, 2000-hour TBO Rotax 914 as the forward-looking powerplant of choice for his company’s LSA models.

“Having the 914 on the airframe gives a buyer the advantage should the LSA speed rules relax. If those rules change, the 912 could lose some value,” he said. We’ll look at Rotax field support and reliability statistics in an upcoming report.

How you might choose

The takeaway of our investigating comes close to contradicting the assumption that an American-made LSA will offer the easiest serviceability from a parts availability standpoint. Our own experience working on the shop level proved that quickly sourcing parts for American brands—including Part 23 models from Beechcraft, Cessna and Cirrus—isn’t always a sure thing.

More of a gauge at how parts support might go for any LSA—foreign or domestic—is the size of the fleet, the size of the parts and support infrastructure and whether or not the company has a diverse product line, to include Part 23 models. Still, you should expect longer periods of downtime while shops source special-order parts outside of the U.S.

Thankfully, more established brands seem to be figuring out how to get better at keeping more parts on hand and LSAs in the air.