Giving Cirrus and Diamond their due, “crashworthy” doesn’t immediately leap to mind when thinking about little airplanes. The vast majority of the fleet is old school, with little flail space, single diagonal seatbelts and many aircraft with non-energy-absorbing seats. Most of us just grit our teeth and fly on.

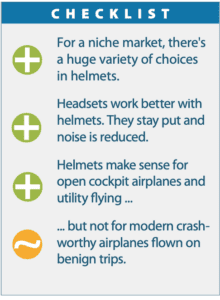

Improved seatbelts are a plus as are retrofit airbag belts. But how about another idea? A flight helmet. We wear helmets on motorcycles, bicycles and when snowboarding and skiing, why not for flying? It’s a question several manufacturers have pondered and they’re finding some sales for specialized aviation helmets. But, well, aren’t we stepping a little overboard here? After all, how much risk can we mitigate before we just chain up the hangar and hide in the house?

On the other hand, to my surprise, there’s actual research data that indicates that helmets do indeed confer benefits in a crash, albeit the circumstances tend to be edge cases. One compelling reason to consider a helmet is that it’s (a) a better way to perch a headset on your noggin and (b) the headset may work better.

WHY BOTHER?

Helmets popped up on my radar last year for two reasons. One, I saw a video by Maxime Compagnon who crashed high in the Austrian Alps with a friend. (See contacts box for a link.) He was wearing a helmet and although it came off his head, he credited it with preventing further injury. Second, I noticed that pilots flying in ever-popular STOL competitions tend to wear helmets. This makes sense because they’re sort of doing the aeronautical equivalent of riding a motorcycle on a racetrack. Head protection can’t hurt and it could help in that nasty corner of the risk envelope where your head is bouncing off the overhead.

Long before I noticed this, others have been thinking about the value of helmets and designing them to provide a level of routine protection in the cockpit. Although we haven’t taken much notice of it, serious research has been devoted to the kind of injuries that occur in general aviation crashes and the results aren’t surprising.

A study of general aviation crashes done in the U.K. in 2005 found that two-thirds of the victims had head injuries, most of which contributed to death. While it may seem obvious that a helmet could help here, that may not always be the case. The injuries were often so-called “hinge fractures” caused by impact forces through the mandible to the base of the skull. They’re the result of a combination of poor flail space in the cockpit and barely adequate restraint.

A later study, also in the U.K., found that of 6080 patients admitted with aviation-related injuries over a six-year period, head injuries were most prominent among patients who died, although lower limb fractures were the most common injuries. Because it relies so heavily on aircraft of all sizes for transportation and recreation, Alaska leads the U.S. in aviation accidents. In 2009, the

state’s regional flight standards office took a run at reducing accidents by studying 649 crashes in detail. These included autopsy reports on some of the 113 people who died in those crashes. The report concluded that helmet use, which is required for pilots flying state-owned aircraft, was a factor in reducing deaths. The surgeons engaged to do the research found 27 autopsy reports that involved serious head injuries and they estimated regular helmet usage could have saved up to 33 lives.

HOW MUCH PROTECTION?

The Alaska study may be best in class for research on civil helmet usage, but it was largely silent on what type of helmet to use and specifically what injuries might be prevented. A common type of facial injury is called an orbital fracture and occurs when blunt force from striking the panel, a window frame or A-pillar fractures the bony structure around the eyeball.

It’s unclear how or even if an open-face flight helmet would prevent this kind of fracture. As far as we know, no civil research has been done on this topic. However, investigations have been done on bicycle helmets, which are also open face, and one study found those helmets do protect the upper part of the face, but not the jaw and the nose. This is because helmets have a protruding ridge that forms an impact “shadow” reducing blunt force. Whether that helps in an aircraft crash is unknown.

Also not studied is the effect a helmet might have on causing a cervical injury because of its weight, something that might not occur without the helmet. Auto racing, of course, addressed this problem with the HANS device that uses a shoulder-supported restraint system to keep rapid onset G forces from snapping the helmet forward or back. For as we’ll as this works in race cars, it wouldn’t be practical in airplanes. And maybe helmets aren’t, either, at least as a routine safety device.

You may not have looked in detail, but there are a lot of helmet choices and ever more in just the past few years. Helmets have generally been favored by ultralight and open cockpit pilots, plus agpilots, utility aircraft operators and helicopter pilots. There are lots to pick from across a range of prices and styles.

One style that isn’t we’ll represented is the aviation equivalent of a full-face motorcycle helmet. This may or may not be what you’d want to protect against facial injuries, but being the owner of several of these for motorcycling, I doubt they’re practical for flying. Still, worth mentioning is a Canadian company called QH Aviation Services that can customize a full-face or any other type of helmet with aviation compatible headphones and mics. They can fix you up with a kit for this, if you’re inclined. Otherwise, you’ll find no fewer than a dozen choices of various kinds on the Aircraft Spruce and Specialty website. These range in price from under $300 to more than $3000.

Another company, www.flighthelmet.com, also offers a full line of fixed wing and helicopter helmets across a range of prices and styles, some equipped with built-in headsets and some not. They also offer refurbished military helicopter helmets for under $1000.

As with motorcycle helmets, there are standards for aviation helmets, too. None of these are based on the kinds of injuries pilots are likely to suffer, something that’s also true of motorcycle helmets, which are essentially designed to theoretically mitigate certain acceleration limits and provide puncture resistance. Whether it matters that these helmets meet these standards or not is an open question. Two that I tried do meet published standards.

FLIGHT TRIALS

I hadn’t intended to make this report a flight comparison of helmets because there are too many of them to make sense of. To my surprise, I couldn’t get many samples because of pandemic-related supply chain issues. Comtronics, for example, is a leading supplier but was unable to supply any samples. Another company, Lift Aviation, whose AV-1 KOR helmet is a terrific looking product, did not return calls or emails. Rob Irwin at Aircraft Spruce told me these products have been out of stock for months with no estimates on when they’ll be available.

I was able to obtain three helmets just to test fly the concept. David Clark sent its old standby K10, Bonehead Composites sent an Aries carbon fiber helmet and a new company called Sky Cowboy Supply sent a trial version of its lightweight flight helmet.

First the Aries, which, at $3033, ought to be a premium performer. It is. The helmet is we’ll crafted from carbon fiber and provides generous coverage around the ears and cheeks. It’s available from Spruce in various models that can be customized. For example, the basic version with built-in audio sells for $1595. The premium model I tried had a LightSpeed Zulu ANR.

I found the helmet snug and comfortable and this contributes to its performance. In the stupid noisy Cub, it dramatically reduces perceived noise level and the clamping pressure improves the Zulu’s ANR performance.

I was actually able to reduce the radio volume for a change. The helmet has a retractable visor that stores under a carbon fiber guard. It’s optically clean and easy to deploy and stow, although it did interfere with my glasses. I’m not sure how many people would spend this much for a helmet—or even half as much—but it certainly delivers on performance. It is likely to be a little sweaty in hot weather, although Bonehead has added a ventilation feature.

Lower on the price scale is the Sky Cowboy helmet, a lightweight glass-reinforced polycarbonate shell with an expanded polystyrene inner liner similar to a motorcycle helmet. It’s modeled on a tactical-style helmet made by Team Wendy and is available in several colors. You can also buy it already fitted with a Bose A20 ($1765) or as a kit for $425 that you can DIY your own headset.

The helmet is light and airy with good ventilation and a comfortable fit. It meets the ACH Blunt Impact standard applied to military combat helmets. It’s not as quiet as the Aries and I found the clamping pressure of the A20 on my sample was too light. If I bought one, I’d figure out a way to tighten that up. The visor on this helmet is excellent; easy to use and optically pure.

One complaint—this applies to the Aries as well—is the quick release on the retention strap. As I was researching helmets, the Australian ATSB announced a recommendation that pilots doing low-level work fly with helmets, this following a fatal helicopter crash in which a pilot who was wearing a helmet had it come off during the crash. I would prefer the typical double D fastener used on motorcycle helmets. It’s far more secure. A helmet is useless if it comes off in the heat of impact.

David Clark’s K10 has been a standby helmet for years. It’s built to a military standard called MIL-H-85047A of injected molded nylon with attached energy-absorbing pads. The helmet has a cloth inner liner that a headset can be mounted in and that snaps inside the helmet. There’s a separate nape pad for the back of the helmet.

The K10 has snaps for a shield, but I didn’t try that. In any case, it’s not retractable as with the Bonehead and Sky Cowboy products. The liner will accommodate David Clark headsets and may or may not fit others. It’s light and we’ll ventilated, but not as comfortable as the Sky Cowboy. It retails for about $400.

WANT ONE? NEED ONE?

While I think helmets add a meaningful degree of crash protection, my view is that the first line of defense in an airplane that doesn’t already have them is four-point restraints. The next step up is airbag seatbelts which are, increasingly, finding traction in the aftermarket. After that, a helmet could be useful in certain airplanes or flight ops.

I wouldn’t wear one in a Cirrus or a Diamond, but I’m thinking about one for the open-door Cub. If I were doing serious adventure flying or STOL contests, a helmet would be a must-have. My first choice would be the Aries, but I can’t justify the cost, so the nearly-as-good Sky Cowboy would be the high-value option.

I would probably buy it with the headset already installed so I’d have a plain headset and a helmet-equipped version. I have no illusions about the protection helmets might offer, but it’s some. The appeal to me is how much they improve headset comfort, performance and convenience. For an accompanying video on helmets, see tinyurl.com/2p8jzfcp.