No matter how many times we hit the delete key, 2020 is still here. With Abby Normal the new normal, a lot of pilots have been flying infrequently at best, with many unable to do any aviating at all.

Our readers are nothing if not perceptive—they know that a pilot who isn’t flying regularly can be a ball of aircraft aluminum looking for a place to a stop—and they’re looking for ways to get back into flying, when the opportunity arises, safely, without breaking the bank. They are also expressing concern about the insurance market and rightfully worried about what will happen to their insurance rates when renewal comes around and they haven’t been flying.

We’ve looked at the issues involved with returning to active flying after a layoff and spent some time talking with instructors and reviewing material specifically designed for pilots who want to get back into the air. We also are very aware that COVID-19 job losses and job cutbacks have meant that a lot of pilots who are determined to resume flying are doing so on tightened budgets. Our recommendations are based on getting safely back in the air in a cost-effective manner.

FREE STUFF

There are a number of commercially available books and study courses designed to get rusty pilots back into the cockpit. All of the ones we’ve looked at are we’ll done. However, because we don’t have any advertisers to aggravate with our comments, we’ll say flat out: There is so much good free stuff available, that beyond keeping your AOPA membership current, you don’t have to spend a cent to get your hands on excellent recurrent training materials.

At the same time, we’re going to recommend—in the strongest terms possible—that the first few flights you make be with an instructor. We’ll get into what to do during that time with an instructor in more detail shortly. For now we suggest that you take the money that you don’t spend on commercial review materials and spend it on a few hours with a CFI.

We also recognize that it’s impossible to social distance in a four-place single. If you take dual, follow CDC guidelines for protecting yourself and the CFI by wearing a mask (we’ve found no problem using a headset and a mask and talking on the radio), using your own headset and wiping down interior surfaces. We note that Redbird Flight Simulations (www.simulators.redbirdflight.com) allows social distancing—the pilot flies the simulator with the instructor outside.

GROUND PREP

Take a look at our online sister publication AVweb (www.avweb.com) for its vast library of articles on everything involved with flight safety and efficiency. John Deakin’s pieces on engine operation, for example, are classics that have been relied on by pilots for decades.

The FAA (www.faa.gov) has a stunning amount of free flight safety material. Want the most current regulations? Don’t buy them. Every single one is free on the FAA’s website, as is the complete Aeronautical Information Manual, all advisory circulars (solid information on a vast array of aeronautical subjects) and flight training manuals such as the Airplane Flying Handbook and Instrument Flying Handbook—just about anything you need to refresh your aeronautical knowledge.

WINGS

The FAA WINGS program (www.faasafety.gov/WINGS) was designed to address primary accident causal factors in general aviation. It consists of a series of phases that you tailor to the type of aircraft you fly with online courses and guided dual instruction. Completion of a phase counts also counts as a flight review. Our sister publication IFR Refresher once referred to the WINGS program as a silver bullet for flight safety because so few pilots who were current in the program were involved in accidents.

AOPA (www.aopa.org) and Hartzell Propeller teamed up to create the Return-to-Flight Proficiency Plan. It contains a series of what we consider to be well-produced videos on topics that will help pilots update and refresh their aeronautical knowledge. While we’ve included this in our free stuff collection, AOPA membership is required. We recommend AOPA membership if only because of AOPA’s strong legislative efforts on behalf of the pilot community and the magazine members receive every month.

One of the most important documents for a pilot to review in detail before getting back into the air is the POH or Owner’s Manual (POHs did not come into common usage until about 1976) for the airplane you fly. We recommend taking some time to read through the sections on normal, abnormal and emergency procedures, systems and performance at the very least. We guarantee that you will find stuff you either didn’t remember was in there or didn’t know about.

Especially if the fuel system is more complicated than an “On/Off” system, make sure you understand how many tanks the airplane has and how to make sure you’re selecting a tank that has fuel in it (make absolutely certain that you know which end of the fuel selector knob points at the tank selected—some are not intuitive) because a significant percentage of accidents involve fuel mismanagement.

Every month when we look at accidents for the Used Aircraft Guide we can count on at least 5 percent involving a pilot who ran a tank dry and didn’t then select a tank that had fuel in it. Also, make sure you know the procedure for getting the engine stared again if you do run a tank dry. It may require taking action other than just moving the fuel selector.

EMERGENCY PROCEDURES

If you can, go out to the airplane, sit in it and run through the full emergency procedures section in the POH. If you’re a renter, do it when your airplane of choice isn’t scheduled to fly—so you can keep this a free exercise. CFIs told us repeatedly that one of the weakest areas they saw in recurrent training was emergency procedures—because they don’t get practiced in normal operations. It seems to be especially true with pilots who fly frequently and claim that they don’t need recurrent training because they fly frequently.

Pilots reported to us that sitting in the airplane, going through the POH emergency procedures section and moving the controls for each step proved to be a big help for them in getting comfortable in the airplane again. When they went through the engine failure after takeoff section, they also gave a thought to how far they were going to have to shove the nose down—and how fast—to avoid stalling and have enough energy to flare and land.

We in aviation have repeatedly proven the truth of the more than 2000-year-old statement by the ancient Greek poet Archilochus: “We don’t rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training.” As pilots, we do the stuff we’ve practiced well—when we try something new, not so much.

CFIs watch that play out in recurrent training all of the time—it takes three or four tries for the pilot to handle an engine shutdown on a twin without losing a lot of altitude or control becoming questionable. In the real world you have to get it right the first time, so you have to have practiced emergencies recently.

TAILOR YOUR FLIGHTS

We strongly recommend that when you are able to start flying again that you make the first flight with an instructor. We spoke with the Kathryn Robine, a former airline pilot who currently instructs at the Michigan Flyers, a large flying club in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She told us that the club requires that any pilot who has not flown three hours and made nine landings in the preceding three months has to fly with an instructor and be signed off before flying club airplanes solo or with passengers.

Robine told us that her experience was that the aeronautical skill that erodes fastest was making landings, particularly in a crosswind. That matches what we’ve seen over the years in reviewing NTSB accident reports for the Used Aircraft Guide in each issue of Aviation Consumer.

Robine also recommended that a pilot talk with the instructor before the dual session so that it can be tailored to the type of flying you do and your needs.

Denver-area CFI Michael Shannon said that in pre-instruction conversations with his clients, he asks them to outline their flying goals for the next year. We think that’s a good way to help set up the syllabus for the time in the airplane. Shannon also commented that the geographical area (including degree of airspace congestion) where a pilot most often flies should affect the way a CFI approaches training to get the rust off.

Michigan Civil Air Patrol instructor Kary Lucas told us that she emphasizes the stick-and-rudder basics in return-to-flying flight instruction and talks with pilots ahead of time about what type of flying they like to do and what makes them uncomfortable. She said that some work on slow flight in various flap and gear configurations often helps expand a pilot’s comfort zone and winds up improving their ability to make crosswind landings.

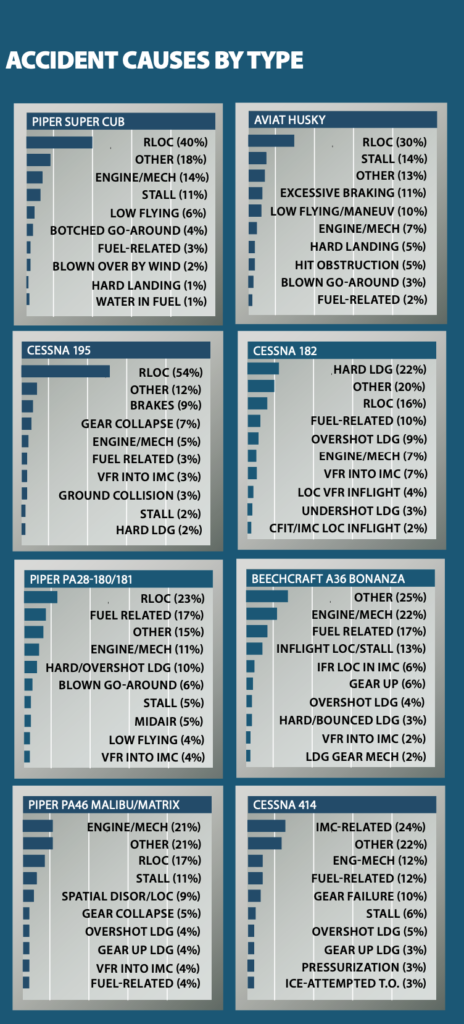

We also recommend tailoring return-to-flight training for the risks associated with the type of airplane you regularly fly. On the previous page, we reproduced the accident causation data on eight types of popular airplanes. Before returning to flight, we suggest searching back issues of Aviation Consumer for the most recent Used Aircraft Guide for your type. After reviewing accident data, we have some recommendations based on aircraft type.

TAILWHEEL

Loss of control during landing rollout is the almost always the number one reason tailwheel airplanes visit the body and fender shop. Their rate of RLOC crashes is generally two to three times that of their nosewheel brethren. Real pilots may fly tailwheel, but they wreck a lot of airplanes.

We cannot overemphasize the need for solid landing training when returning to fly tailwheel airplanes—with the pilot demonstrating proficiency in three-point and wheel landings after approaching at no more than 1.3 Vso. We see too many accident reports where the pilot came smoking down final, made a wheel landing at high speed and lost control before the aircraft had decelerated enough to put the tailwheel on the runway.

SINGLE-ENGINE CRUISERS

With the steering wheel up front, the rate of RLOC accidents drops off, although landing-related accidents (hard/bounced landing, RLOC and loss of control on go-around) are still close to the top of the crunch parade.

The next area of concern is fuel management. We recommend that return-to-flight training spend time on fuel system operation and management and engine restarts after running a tank dry.

HIGH-PERFORMANCE

As speed goes up, the frequency of IMC-related accidents goes up, many because of spatial disorientation or a pilot having difficulty hand-flying in the clag. Dropping a wing because you glanced down at your iPad will generate a high-speed diving spiral distressingly quickly in a high-performance machine. Accordingly, we recommend that any instrument-rated pilot undergoing return-to-flight training in a twin or high-performance single complete an IPC.

ON YOUR OWN

Once you’ve gotten the skills brushed up with a CFI, how can you keep them as sharp as possible when you can’t fly as frequently as you’d like? From our talks with CFIs we came away with an overall strategy that is pretty simple. First, in debriefing your last CFI flight, find out where the CFI thinks you should concentrate when you practice. Use that to start creating your checklist of maneuvers to practice.

Once you have the list, put it into an efficient order. Do you have to ferry some distance to the practice area? What can you do to make that time valuable? Try some coordination exercises—rolling back and forth from right to left banks while using the rudder to hold the nose on a point directly ahead of you.

If possible, fly when others aren’t so that you can fly a tight pattern and get in more landings than when you have to follow that guy who flies downwind to the next county before turning base.

Do everything you can to be ready to go when you start the engine. You don’t want to be sitting around with the engine idling while you mount your iPad and input your route.

If we in aviation have learned nothing from the COVID-19 pandemic it’s that flying time is precious. Make the most of every moment of it.