As the average age of general aviation pilots continues to climb—during a “hard” insurance market—we hear horror stories of pilots being unable to find coverage, having coverage canceled or facing premium price increases they simply cannot afford.

As we started our look into the matter, we found consistent evidence that once a pilot hits 70 it’s increasingly difficult to get aircraft insurance and prices go up, sometimes painfully. However, as we looked at available data on the actual accident risks for aging pilots we found inconsistent results—published studies showed the accident rate for aging pilots dropped (but if an aging pilot had an accident it was more likely to be fatal), while AOPA, not providing citations, said that studies showed “older pilots are not as sharp as younger pilots who had similar amounts of experience” and “given sufficient experience, older pilots performed better than their younger counterparts.”

We also heard AOPA President Mark Baker say, at the September Spokane, Washington, “hangout,” that two new companies were going to join the aviation insurance market and they would use more accurate risk data for setting pilot insurance premiums.

What’s going on?

Our initial research prompted us to do a deep dive into insurance coverage for aging pilots. We’re reporting what we found here—starting by looking at the aviation insurance world, how it’s organized and what you’re buying when you buy insurance for your airplane. We’ll then discuss what we found when we sought out peer-reviewed, scientific research into the relationship between pilot age and accidents, discuss what accident/loss data is available to insurance companies in setting premiums and then look at strategies that all pilots, but especially those over age 60, can use to positively affect their insurance premiums.

TYPES OF INSURANCE

Insurance is an agreement between you and the insurance company. It’s a contract—and the principles of contract law in your state (insurance is regulated at the state level) apply to your obligations and those of the insurance company

That provides a segue into the two types of insurance that may be purchased by the owner of an aircraft. They are ordinarily purchased together, but some owners prefer to buy just one of the two—usually because of cost.

HULL INSURANCE

The first is hull insurance, which is based on an “agreed” value of your airplane. You determine what you think your airplane is worth and, unless the insurance company thinks that you’re way out of line, that’s the value of your airplane under the hull policy.

If your airplane gets damaged and the insurer makes the determination that the damage is so severe that the cost of repairs exceeds the agreed-upon value—and it’s the insurer’s call—the aircraft is considered a total loss, and it’s “totaled.”

You then have a decision to make—you turn the wreckage over to your insurer in return for a check or you decide to keep the wreckage and not take the money.

THE VALUE’S THE RUB

With the skyrocketing value of airplanes—and their repairs—over the last few years, an old problem has reappeared to bite owners—underinsuring their airplanes. We saw it happen to one owner in the last month after he forgot the Firestones before alighting on the runway. Damage was limited to belly skins, the step, the flaps and the prop. There will have to be an engine teardown because of the prop strike.

The problem is that estimated repairs are over 90 percent of the agreed hull value because he hadn’t adjusted the hull value in the ten years that he’d owned the airplane—and it had more than doubled in value. Under the terms of his particular policy (not all aircraft policies are the same), the insurance company can declare the airplane a total loss if the estimated cost of repairs exceeds 90 percent of the agreed-upon hull value. That’s common in hull policies as the final cost of repairs almost always exceeds the initial estimate and insurers justifiably don’t like paying out more than the agreed hull value to repair an airplane.

This owner is now in a box. Does he eat the cost of repairs himself or does he take a check for the number he had set for the airplane’s value and give up an airplane that is going to be worth quite a bit of money once it gets about $60,000 in repairs?

Our recommendation when it comes to hull insurance is to make sure that every time your insurance comes up for renewal you evaluate the value of the airplane, especially if you’ve done any upgrades, such as avionics, interior or paint.

GOING BARE

Some pilots, when faced with very high hull premiums, or unable to get coverage, elect to “go bare” for hull coverage. That means that they don’t buy hull insurance and have the resources to pay for repairs themselves after an accident or will just sell the wreckage and walk away from the airplane.

We’ve seen a number of pilots make that personal decision. Sadly, we’ve also seen a number of pilots who had a far greater opinion of their flying skills than was warranted—Dunning-Kruger Effect anyone?—make the decision when they simply got pissed off over a premium price bump—”I’ll show those insurance so-and-sos, I won’t pay their extortionate prices.” They then tried a crosswind landing that their skill level couldn’t handle and were out many tens of thousands of dollars after the dust settled.

Our considered recommendation: Before you make the decision to forgo hull insurance, schedule some dual with an instructor who will give you a no-holds-barred evaluation of your level of skill. Then listen to her. This is not the time for your ego to be writing checks your skills can’t cash.

If you are paying on a loan on your airplane, going bare is not an option. Your loan agreement requires that you carry hull insurance. Trust us on that one.

LIABILITY INSURANCE

The other half of aviation insurance coverage is protection for liability that you may incur because it was your sweaty hands on the controls when things went south.

The amount of liability coverage you buy is based on your discussions with your insurance broker and perhaps your attorney, and what you think is best to protect your assets should something go wrong inflight.

We won’t go into the various coverages available other than to say that insurers look at your risk of having an accident and the potential injuries to others and what it’s going to cost the insurer to settle the claims. Considered into that calculation is that high-dollar airplanes tend to have high-dollar passengers inside—and it’s usually passengers who are the ones affected adversely in an accident.

On top of that, older pilots often carry older passengers and as we age, the degree of injury we suffer in an accident increases. What might be bumps and bruises at age 25 are broken bones and months of rehab when we’re 65—driving up payouts by insurers.

We have found that aging pilots who either cannot buy liability insurance or cannot get the policy limits that they need to protect their assets have looked at alternatives that included not flying, not carrying passengers and switching to a simpler airplane with fewer seats. We think that all are viable strategies.

We are aware that some pilots have elected to go bare when it comes to liability coverage when they feel the premium is too high or coverage is not available. We urge extreme caution if making that decision as a runway loss of control prang with a couple of passengers can mean that your retirement will change from the luxury condo on the beach to passing out shopping carts at the local supermarket.

If you screw up and kill a passenger and yourself, it’s your family who will be impoverished and their subsequent opinion of you as a pilot and responsible family member will not be printable here.

TYPES OF INSURERS

There are only about 12 companies in the aviation insurance market. That’s not surprising when one considers that there are only 220,000 airplanes and 600,000 pilots in the U.S. There are more cars than that in any small city, so the aviation insurance market is tiny.

All but one of the insurers require that you purchase their product through an insurance broker. You contact a broker, provide the information on your airplane and yourself and the broker goes into the market to get quotes for coverage—types of coverage available and prices (all aviation policies are not alike—unlike automobile policies).

The broker is your agent. That means the broker’s duties and obligations are to you, not the insurance companies. It behooves you to sell yourself to your broker so that she or he can sell you to the insurers. Your broker will also be a wealth of information as to how you can present yourself best—such as telling you to get some flight time in the make and model of airplane you are planning to buy so that you don’t have to put “zero” in the insurance application blank for time in make and model.

Because the aviation insurance market is so small, you generally can’t skip to another broker if you get quotes you don’t like. The insurers have quoted you and your airplane, so they generally won’t do it again. Plus, if you keep switching brokers over the course of a month or so, the insurance companies are likely to tell you to take a hike and won’t write insurance for you at all. It’s a small market with long memories.

One company, Avemco, is what is called a direct writer. You contact the company directly, provide your details and you get a quote. Our readers have given Avemco good marks for its customer service, especially pilots over age 70.

PEER-REVIEWED STUDIES

In preparing this article, we worked with Dr. Jay Apt, a multi-thousand-hour general aviation pilot, who has a Ph.D. in physics, is a professor at Carnegie Mellon University teaching—among other things—risk analysis, did four missions in the space shuttle and has been researching the matter of aging pilots for some years. He sought out peer-reviewed studies on general aviation aircraft accident risk versus pilot age and found only two that were recent. We’ll review them briefly.

The first, from 2010, by Massoud Bazargan and Vitaly S. Guzhva of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University entitled Impact of Gender Age and Experience of Pilots on General Aviation Accidents, looked at the number of accidents versus, among other things, pilot age. The study broke down pilot age in ten-year increments but, unfortunately, then lumped everyone over 60 in one group. Accordingly, we put little value on the results because, while we liked them, they didn’t address the issue we’re trying to track because insurance companies seem to be drawing their lines beginning at age 70.

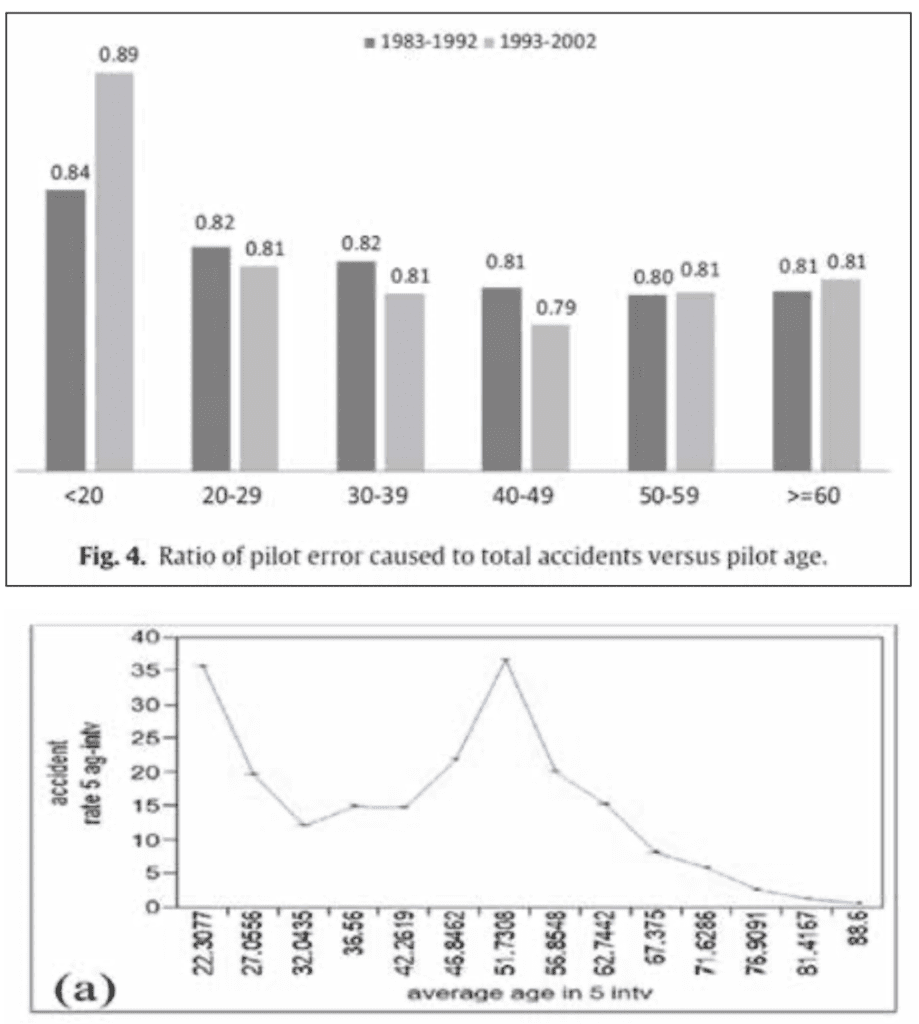

We liked that the authors found that the ratio of pilot error accidents to all accidents ranged between 0.79 and 0.89 for all ages of pilots. The graph of the results of their two 10-year data sets is on the page after the sidebar. The difference in the ratios for pilot error accidents—0.79 to 0.89—is not statistically significant.

The second report, The Relationship between General Aviation Pilot Age and Accident Rate, by five authors in the Mehran University Research Journal of Engineering and Technology in July 2020—lead author Khawar Naeem—used what we think was a solid approach to the subject. It broke pilot age into five-year increments through age 88 and the authors had two separate Ph.D.s independently read all of the 571 NTSB reports examined and extract the desired data.

ACCIDENT RATE

The variable examined was accident rate, which we think is more significant than looking at total accidents for an age group. The result of their work is graphed on this page. It shows a peak in early age 20s (hold my beer and watch this) with the rate steadily dropping to the early 30s, and then curving up to a similarly high peak as the 20s at age 51 (midlife crises?). It then drops steadily—passing below the early 30s’ value at age 62—until it bottoms out with the lowest accident rate for pilots at age 88, the end of the data.

To us, that’s striking, and it initially caused us to be ready to argue that the insurance companies were unreasonably discriminating against aging pilots. However, we backed off for four significant reasons: 571 accidents is not a statistical universe, NTSB data don’t give much information as to the severity of accidents nor any as to the amount the insurance companies paid out following those accidents—and this is a big one—only a fraction of aircraft damage events make it into NTSB reports.

INSURERS’ DECISIONS

When we turn the page to decisions made by insurance underwriters regarding accident risk by age, appropriate premiums and coverage, we find that they have far more mishap data than does the NTSB and they know how much they paid in the wake of each mishap and subsequent claim.

The money that the insurance company has to pay is the only thing that matters to the insurance companies and their risk analysts as they try to set premiums at a level that will let them stay in business. That’s pure capitalism, and the irony of American pilots complaining about it is palpable.

We have repeatedly reached out seeking to talk with underwriters—the ones who make decisions on whether to insure and what premium to set—at aviation insurers. Thus far only one has been willing to speak with us, and that has been with the condition that we do not disclose the name of the company or the underwriter. What we learned was consistent with what we obtained from other sources including numerous insurance brokers.

The underwriter was not surprised by the results of the two studies above and generally agreed with them to the extent of the information available to the authors of the studies. The underwriter pointed out that their company has more than 60 years of accident, incident and claims data driving insuring decisions. The underwriter I spoke with is an experienced pilot. They did not have enough information to say whether it is common for underwriters at other aviation insurers to be pilots.

The extensive and detailed loss history—and analysis thereof—is proprietary to an aircraft insurer. It cost significant bucks over many years to create and plays an overwhelmingly large role in whether that company is going to be financially viable. Of course we asked to see the loss data broken down by age. Not surprisingly, the request was politely refused.

AGING PILOT STRATEGIES

We spent most of the rest of our conversation asking the underwriter how an older pilot can get the best premium and have coverage as long as possible. They recommended:

• Take regular recurrent training—at least every 12 months, not 24. Take a flight review from a “tough” instructor, one who won’t pencil-whip a review.

• If you are considering a purchase, make sure you can insure the airplane before you buy.

• We heard the next one from another source as well—insurance broker Scott “Sky” Smith—if you are considering stepping up into a twin or turbine equipment, do it before you are 69. Otherwise, you will almost certainly be unable to find coverage.

• If you are over 70 and fly a complex or tailwheel airplane, seriously consider moving to a single-engine piston, fixed-gear, nosewheel machine, but not a high-dollar one such as a relatively new SR22 or Cessna 182.

• Fly often—30 hours a year is not attractive to insurers; 100+ hours is.

• Stay with the same insurance company. Loyalty is recognized.

• Stick with the same broker. If you’re over 70 and change brokers the insurers will suspect that there’s something wrong and your broker dumped you. “Shopping” brokers is a common tactic used by desperate older pilots (who may be showing the first signs of dementia) who can’t get coverage or are showing unreasonable anger over a premium price increase.

• Do not let your insurance lapse. If you do, it will be essentially as if you are shopping for insurance for the first time as an older pilot, and it will be ugly.

• Stick with ownership of airplanes built in quantity so that parts are available.

WHAT’S NEXT

If the rumors are true and one or two companies enter the aviation insurance market we can expect some “softening” of the market as competition comes into play and insurers cut premiums or back off on conditions for coverage to maintain market share and cash flow.

According to AOPA’s Mark Baker, at least one of the new insurers is going to use some form of tracking to analyze how each insured flies (ADS-B?) and adjust premiums to reflect the true risk.

There’s a degree of Big Brother in the tracking concept. However, smart pilots who do their best to fly safely already provide their insurers with as much information as they can to convince them to keep premiums low.

Of concern, the spectre hanging over the entire aviation insurance world is one of the many side effects of Putin’s war—there are some $10 billion in American- and British-insured aircraft locked up in Russia that may prove to be write-offs. They are part of the aviation insurance risk pool in which we swim. We don’t like to think of the repercussions on the aviation insurance world if claims have to be paid on even half of those.

CONCLUSION

In our opinion, most aviation insurers are making risk decisions based on extensive, proprietary loss data available in-house—although we have seen exceptions such as the indefensible requirement to have a third-class medical rather than BasicMed.

If allegations that aviation insurance underwriters are without specialized aviation experience and are spending most of their time doing risk analysis on construction equipment are true, we’ll join in the chorus of righteous indignation.

We’re hoping that the rumors of new insurance entrants into the field are true. More competition is usually better for aircraft owners.

Nevertheless, no matter what happens, we think that an aircraft owner is wise to follow the strategies we outlined above to maximize the ability to get coverage and minimize the cost of premiums. We also strongly recommend that pilots take AOPA’s excellent online course for aging pilots: Aging Gracefully, Flying Safely.