Interestingly, the number of U.S.-registered aircraft is increasing, while the number of pilots is decreasing. (Wikipedia says there were 609,306 licensed pilots and GAMA counted 211,000 registered aircraft.) But even allowing for flying clubs, partnerships and the graying and thinning of the pilot population, this still means that there are a lot of pilots who are flying aircraft that they do not own.

If you are one of them, this article—a fresh look at non-owned aircraft liability insurance coverage—is for you. Truth is, to understand what sort of coverage different types of pilots need, it helps to know what they are already covered for, and what they are not. Here’s a primer for shopping.

A DIVERSE POPULATION

Some of the nearly 610,000 pilots are following the siren song of future airline jobs. Others are the growing numbers of CFIs who are providing that flight instruction. Some are pilots hired by an owner to ferry the airplane, pilots test flying airplanes after maintenance and sales demo pilots. And finally, there are a large number of pilots who are simply borrowing a friend’s airplane (or helicopter) and are reimbursing the owner in some way. Some are using other folks’ aircraft under some form of dry lease. Almost all of these pilots need some form of liability coverage, what insurance people refer to as non-owned aircraft liability insurance, or more simply, renter’s insurance.

When it comes to pilots flying aircraft that they do not own, it is useful to divide the universe into two parts: pilots who are being paid to be in that aircraft because they are working in one way or another, and pilots who are in that airplane for pleasure and business (non-commercial) purposes with the owner’s permission.

Pilots who are using the aircraft with the owner’s permission, and who are not acting as professionals at the time of the accident, will receive virtually the same insurance protection that the owner does. The aircraft liability, in most cases, will protect the permissive user against suits for injury to passengers or people on the ground as we’ll as damage to property.

On the other hand, pilots who are being paid to fly the airplane—like flight instructors and ferry pilots who are providing dual flight instruction or pilot services at the time—are probably not covered for anything under the aircraft owner’s insurance unless special arrangements have been made. Professional pilots who are flying in customer aircraft are typically not covered for bodily injury liability or for damage to property or for damage that they cause to the airplane unless special arrangements have been made in advance.

If someone in the aircraft or on the ground is injured, and it was alleged to be the fault of the pro pilot, he or she will likely be sued. On the other hand, CFIs providing dual instruction in airplanes that belong to their employer probably will be treated as employees, and will be protected by the flight school’s policy.

Flight instructors also face the possibility of yet another threat: Years after signing off a pilot candidate, the CFI can be sued for “negligent instruction.” These suits are fairly rare, but hiring a lawyer to defend yourself can be an unwelcome and expensive proposition. Some flight schools carry this coverage to protect their instructors, but many do not, and generally, the limits available are fairly low.

FLIGHT SCHOOL INSURANCE

A growing part of the pilot population is made up of renter pilots. Some of these are folks who don’t want to take on the expense of owning an airplane on their own, or managing a partnership. Show up at the flight school on Sunday morning and check out the Cherokee—or tailwheel aerobat—for a couple of hours. But believe it or not, we are also seeing younger pilots who are getting their ratings in hopes of flying professionally.

For the true renter, it is important to understand some things about flight school insurance. Most flight schools carry fairly low limits of liability simply because the insurance is expensive. And often, flight school policies cover the flight school, but exclude coverage for the student or renter pilot. Read that again.

Moreover, many flight school policies have high deductibles on their physical damage coverage, and their rental agreements make it clear that the renter is expected to pay for any damage. Helicopter deductibles while the rotors are in motion can be as much as 10 percent of the value of the helicopter. You’ll shell out real money. In many cases, the renter is also expected to pay for the school’s loss of revenue while the aircraft is removed from service for repair.

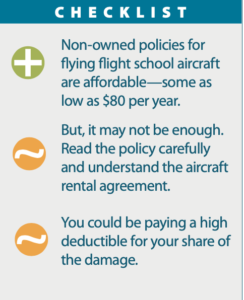

If there’s any hope of not going broke if you break someone else’s aircraft, there are a number of insurers offering non-owned aircraft liability, plus a variety of additional coverages. Which one is best for you depends upon what kind of flying you do. No two of these policy forms are the same, although they do have similarities.

In most of them, Coverage A (or Coverage 1) is bodily injury and property damage liability and medical expenses, but does not include damage to the rented airplane. This coverage is the foundation coverage, and you need to purchase this one if you want to purchase any others. This protects the non-owned pilot in the event of a suit alleging that he or she acted negligently as pilot, and caused bodily injury or property damage to the plaintiff. This coverage is usually subject to a per accident limit of $500,000 to $1 million, in some cases $2 million. There typically is also a per person or per passenger limit of between $50,000 and $200,000.

In addition to the insurer paying off any court judgment or settlement, a large benefit of having liability insurance is that the insurer is required to investigate the claim, and to pay the cost of defending the claim. Without this, you would be left to pay for your own lawyer from the first dollar. The company’s obligation to pay for your defense is without limit, and is in addition to your policy limit. As a rule however, the insurer’s duty to pay for your defense ends when the insurer has agreed to pay the policy limit.

For this reason, we recommend that you consider buying the highest limit that they will sell you. This coverage should be considered by anyone who flies aircraft that he or she does not own. If you own an airplane or helicopter, you may find that your aircraft policy provides some coverage for occasional use of non-owned aircraft.

The second main coverage that can make up part of a non-owned aircraft liability is Coverage B, aircraft damage liability. This coverage is optional, and is typically sold with a per-occurrence limit, usually from $5,000 to $200,000. This is the coverage that will pay if you negligently damage an aircraft that you do not own. This is the coverage that you will need if your FBO requires you to cover his deductible.

Keep in mind that both of these coverages are liability coverages. There needs to be at least an allegation of negligence made against you. We strongly recommend that you never use non-owned liability coverage in place of (or without) physical damage coverage. Here is what can happen.

You are ferrying a friend’s airplane, which has been sold. Unknown to you, the new owner has not placed insurance on the airplane. The engine quits and will not restart. You land in a field and walk away unhurt, but the airplane is a total loss. The engine failure wasn’t your fault, but who will replace the airplane? You were the PIC—and hopefully signed off in type.

GET ADDED TO THE POLICY

This so-called risk-management approach is if you are teaching in or regularly flying in aircraft that you do not own. If the owner and his insurer will agree, ask if you can be added to his insurance. There are three steps that are required.

Make certain that you either meet the pilot requirements or can be listed as a pilot by name. Request a certificate of insurance showing that with respect to instruction that you are included as an additional insured with respect to the owner’s liability coverage. Also be sure you are provided with a waiver of subrogation with respect to physical damage to the aircraft, and are provided with a 30-day written notice of cancellation at your chosen address.

An advantage to this approach is that you may get more protection under the owner’s insurance than you would be able to find on you own. Two disadvantages: The owner’s insurer must agree to it, and it is impractical for a single flight, such as a flight review.

SHOPPING TIPS

If you are shopping for non-owned coverage here are things to consider.

• Look at each company’s aircraft limitations. It sounds basic, but if a company does not cover what you fly, no sense in getting too deep into the weeds. If you fly seaplanes, homebuilts, gliders or helicopters, you may only have one or two choices. Make sure that you understand what the insurer requires in the way of official paperwork. If you are flying experimental airplanes, make sure that the insurer will cover these.

• Some companies offer coverage that pays the aircraft owner’s deductible regardless of fault. If the rental agreement that you sign each time you fly makes you responsible for the deductible, this becomes important

• Some insurers broaden the definition of a non-owned aircraft to include flying club airplanes, provided you do not own more than 20 to 25 percent of the airplane. If you are an owner and are concerned about not having enough liability limit, this might be a way to get it.

• If you are a CFI, look carefully at possible offerings. Avemco has an affinity program with NAFI. C.V. Starr has a similar program with SAFE. Global has non-owned programs with Sporty’s and with EAA, and there’s Assured Partners Aerospace with AOPA. Make sure that whoever you choose covers your signoffs, and under what conditions. For example, do you need to continue coverage in order to be protected if one of your signoffs from years ago has a problem and claims that you failed to adequately instruct her on lowering the landing gear?

• If you plan to fly non-owned aircraft on behalf of your employer, make certain that the insurer that you pick will offer to add your employer as an additional insured, and make sure that your employer will accept the limit that the non-owned underwriter will provide.

• If you are flying an airplane under a dry lease or similar agreement, check your policy wording. Typically, if the term of the agreement exceeds 30 consecutive lease periods, it is treated as if you owned the airplane, and not covered.

CONCLUSION

Non-owned aircraft coverage is relatively affordable. It’s widely available, and there are a number of companies offering it, including Avemco (www.avemco.com), AIG (www.aig.com), Global Aerospace (www.global-aero.com), QBE (www.qbe.com), Americas (www.americas-insurance.com) and C.V. Starr Insurance (www.starrcompanies.com). You can compare coverages on most of these sites and they have portals that allow the consumer to shop and buy online.

Most underwriters that spoke with us said that rates for non-owned coverages have held steady despite the gyrations of the rest of the aviation insurance market. If there is a problem with the non-owned market, it continues to be the lack of available limits. For the most part, the highest limit that you can get is $200,000, and possibly only $100,000.

We don’t feel like that is enough to take care of a serious light airplane accident injury, but perhaps that is the way to cut down on aviation accident suits.