Engage fellow aviators about earning a seaplane rating and it’s likely the name Jack Brown’s Seaplane Base will enter the conversation. That’s because Brown’s, located in Winter Haven, Florida, has trained nearly 20,000 pilots since 1963. That’s impressive longevity in a niche market.

On the other hand, Florida is particularly favorable for float flying and the abundance of fresh-water lakes in the surrounding Winter Haven area makes training at Brown’s seaplane base even more inviting.

Still, with an alumni count of those proportions, I’ve always wondered how intensive the program really is. Moreover, given the nature of seaplane flying, anytime you introduce words like fun, laid back and easy into a flight training curriculum, it’s easy to set false expectations about the experience and the outcome. How proficient might I be with a freshly signed ticket in hand?

To find out, I slapped my money on Brown’s counter and enrolled in its SES, or single-engine seaplane course. My takeaway: It’s fun, stressful, rewarding and relatively expensive. No, the rating is not a gimme. Expect to work hard to earn it, and get back as much as you put in.

Realistic Expectations

Brown’s offers two options for SES training at the private or commercial pilot level. Either curriculum includes 1.5 hours of ground instruction, five hours of dual instruction in one of Brown’s 100-HP Piper J-3 Cubs, plus a checkride, which is administered by company principle and FAA designated examiner Jon Brown or his brother Chuck Brown. The course has a flat-rate fee of $1400, which also includes the examiner fees.

The school says it takes two full days to complete the course. But, that doesn’t mean every pilot will complete the course in two days, or pass the checkride after the initial five hours of dual. While the staff initially offers the caveat that it could take longer (based on pilot proficiency and weather delays), I don’t think this point is made strongly enough when signing up.

Brown’s instructors, on the other hand, make it clear that many students require far more dual instruction than the five-hour minimum and speak up early if they feel that a student will need more time.

You’ll make it a lot easier on yourself and the staff if you show up current, prepared and with your credentials and logbook in good order. This includes having a current medical certificate, your pilot certificate and a valid FAA FTN number. You’ll also need to comply with the school’s TSA-governed identification polices. Bring a U.S. passport or birth certificate. Foreign pilots seeking the rating must meet foreign pilot flight hour requirements and could require a letter from the FAA for foreign license conversion. Basically, don’t expect to show up without completing FAA paperwork.

Brown’s will provide you with a 30-page course guide ahead of time. It’s extensive, and while the material is covered in the initial ground school portion, pre-study is essential. For starters, you’ll want to be familiar with FAR 91.115—the regulation covering right-of-way rules for water operations.

As you would expect, when a seaplane touches the water it must comply with nautical rules, so you’ll need to be familiar with water navigational aids, plus the procedures for anchoring, beaching, docking and ramping the seaplane. There’s also the three main ways of taxiing and turning the seaplane when it’s on the water: idle, plow and step. You might have to sail the seaplane, should the winds be too strong to move it under its own power.

My point is that a student with even minimal seaplane experience will have an advantage over one with none. I showed up with a few hours of dual instruction flying a float-equipped Super Cub. This experience made the initial transition to the J-3—and recognizing the feel of the floats transitioning from displacement to the step—quite easy. I also arrived current in little airplanes, which helps.

An asset was a diverse class. This included Jessica Koss, a CFI and professional pilot at Garmin, a Boeing 737 airline captain, plus the new owner of a float-equipped Piper Super Cruiser. Sharing moral support helped tame the edge when we felt overwhelmed.

Things That Kill

My instructor, Ben Shipps, made it clear from the beginning that I wouldn’t be expected to perform like a seasoned pro on the checkride. That’s just impossible after five or so hours of dual. But what is expected is demonstrating solid decision-making skills. This includes showing healthy amounts of respect for situations that have killed far too many seaplane pilots and their passengers. The list includes, but isn’t limited to, botching the landing in glassy, mirror-like water conditions (due to the absence of depth perception as the seaplane approaches the water), rough water operations, plus operating in and out of confined areas surrounded by terrain and obstacles.

As simple as it may be, you’ll want to be familiar with the J-3 Cub. Want to try your hands at propping while balancing on the deck of the float? You won’t get to—it’s too risky for Brown’s insurance policy.

My instructor spent a lot of time covering what to look for while preflighting the seaplane, which requires having a solid knowledge of the float’s structural design and limitations, while understanding buoyancy theory. This is emphasized on the oral portion of the checkride.

Brown’s Cubs have battery-powered intercoms with old-school (uncomfortable) headsets. Spoiled by years of wearing your fancy Bose ANRs? Leave them at home—the provided phones are hardwired in place.

The aircraft sits on Aqua model 1500 oversized floats, limited to a max wave height of 18 inches. With rigging, these add 250 pounds to the J-3.

With my instructor and me (each weighing 170 pounds) and a fuel tank filled to its maximum 12 gallon capacity, the aircraft was 80 pounds below the 1420-pound gross weight. Since the Cub is flown solo from the back seat, that’s where the student sits, positioned next to the water rudder handle.

The school is fine with students attaching action cameras to the aircraft, and maintenance folks helped me temporarily route my AV cabling for the video chase to this story. But, I was told to turn it all off when I strapped in for the checkride—I get it.

Time to Fly

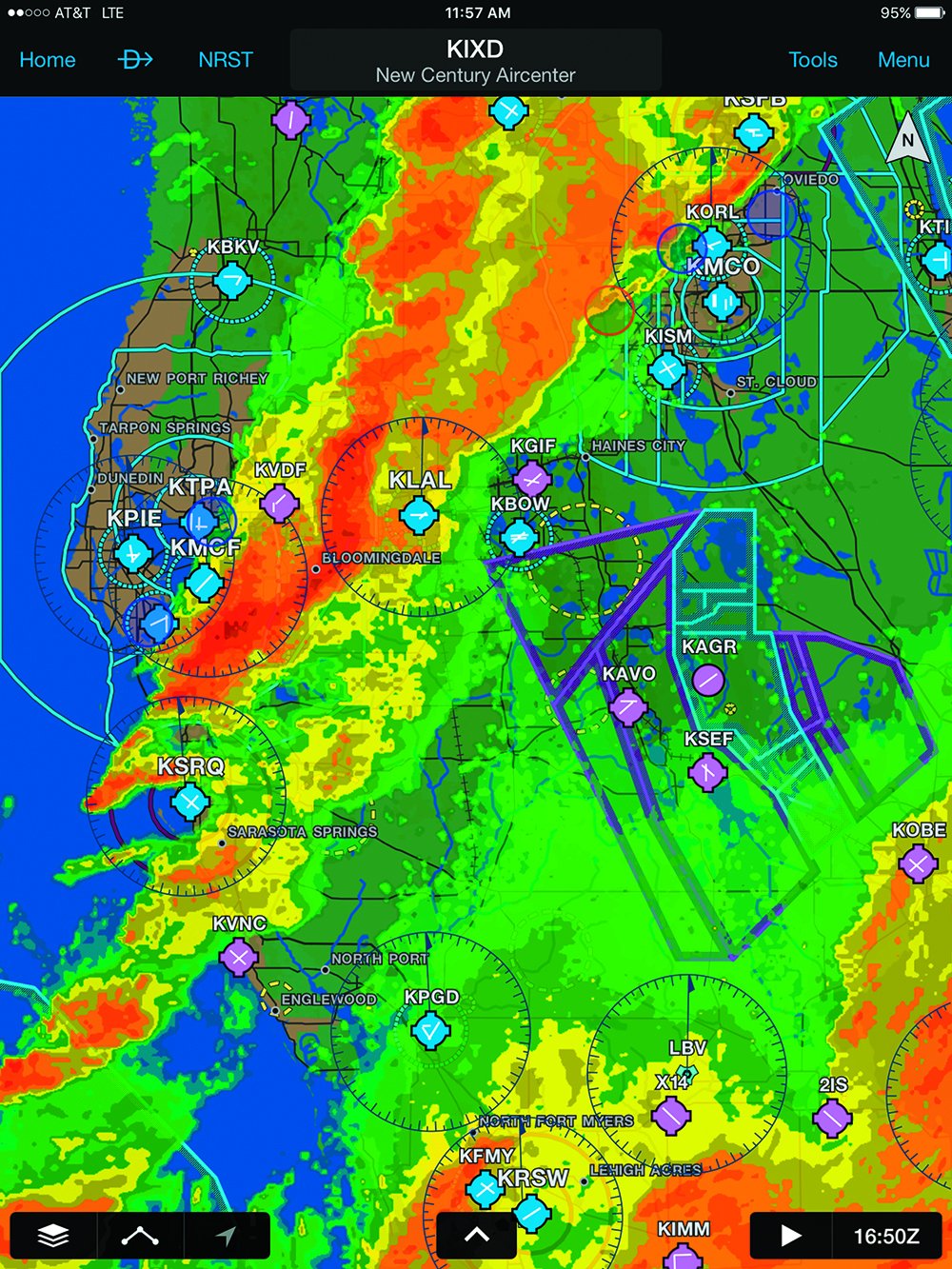

You’ll generally fly in 1.5- to 2.0-hour blocks, depending on the conditions. Brown’s will likely park the Cubs when the wind blows over 20 knots. Since you’ll likely never climb above 800 feet (level-off cruise altitude is 500 feet AGL), the ceiling is rarely an issue, while two miles is the required forward visibility.

You’ll first learn to maneuver the seaplane on the water, and to not hit anything after the ground crew pushes the seaplane off the ramp. Just like taxiing back in and when docking, there is always an audience watching.

Brown’s places appropriate emphasis on good habits for safeguarding the equipment—which could ultimately save you money if you’re training in or operating, your own seaplane. Water operations are harsh on propellers, the engine and airframe.

Plow turning on the water is perhaps the most harsh, since the nose is pitched up significantly under power, reducing engine cooling, forward visibility and increasing water splash through the propeller. You’ll learn to do it, but only as a last resort for when the winds are too strong to turn the seaplane in the direction you need to go while water taxiing.

Idle taxiing using the water rudders is generally the preferred method of getting around, since there’s limited prop spray, efficient engine cooling and good forward visibility.

Following water taxi and takeoff instruction, you’ll perform airwork to get the feel for the aircraft. The J-3 with big Aqua 1500s is docile, with no bad habits in the stall, while 60 MPH is the magic pitch speed during an engine failure.

My instructor rode me hard when it came to maintaining consistent stick and rudder coordination, and stressed the importance of flying square traffic patterns during takeoffs and landings. As a result, I went home with better flying habits and with a sharp eye for reading winds.

Given the constantly changing environment of water operations, you’ll be expected to always know the wind direction and speed, while being able to accurately read its many signatures on the lake water. These conditions are directly proportional to how you manipulate the seaplane in the water and which takeoff and landing procedures you execute. There is a lot at stake.

For example, you might get away with improperly positioning the ailerons in a landplane, but the penance for committing that sin in a seaplane could be a nasty flipover you never saw coming.

Step taxiing is the seaplane equivalent to cruising across the water in a boat at high speed. It’s the fastest way to get around and you might never get used to the centrifugal forces induced while step turning, convinced the seaplane is going to roll over. Of course, turning at high speed from downwind to upwind in strong winds is what capsizing is made of.

There is no room for sloppy checklist habits in a seaplane and the one that will be forever engraved in your noodle is the pre-takeoff/step taxi CARS acronym—carburetor heat, area clear, water rudders and stick back. You’ll quickly learn there is no tolerance for getting lazy with stick position in both pitch and roll axis. Noseovers (catching the tips of the floats in the water) and capsizing are bad days in a seaplane.

Bring on the Boss

When both you and your instructor agree you are ready to face the checkride with Boss-Man Brown (Humble Master Pilot award recipient Jon Brown is indeed the boss and I guarantee you won’t have to be reminded of this fact as you anticipate the ride), it’s time to show him how to fly a seaplane. But don’t rush it.

After logging a total of 5.6 hours of dual instruction, I lacked the confidence (and, in my estimation, the polish) required to successfully perform as PIC under pressure on the checkride. While my instructor was convinced I was being too tough on myself and suggested that one more hour of dual would have me ready, I hit the road to the hotel.

What I needed was a personal debrief, contrasting my day’s performance in the airplane with the way certain procedures are instructed in the manual. Turns out, that was a good call.

The next morning I brought my A-game to the cockpit and somehow, performing all of the procedures and maneuvers that were overwhelming the prior day came naturally. With a total of 7.3 hours of dual instruction, my logbook was endorsed as competent to pass the SES practical test. I admit to some tension.

Before we began, Brown made it clear that the oral questioning and the practical testing would not include any training or advice on his part. I would be PIC, and should he have to take over the controls for any reason (other than a real emergency), it would be an immediate fail, with credit for any successful maneuvers performed. That’s a required standard for any checkride.

Brown shotgunned questions—good ones—about all the stuff that can kill a seaplane pilot. Poor retention of his course manual will show, and he’ll be making notes of it.

As Shipps put it early on, “Mr. Brown has administered nearly 20,000 checkrides. You will not be able to BS this man.” True statement.

Once you complete a weight and balance report to prove the aircraft is below gross weight and within C.G. limits, you’ll demonstrate a thorough preflight inspection. Yes, maintenance folks are watching from a distance.

After push-off and while water taxiing, you’ll execute the method of takeoff which best suits the conditions. Now is not the time to depart the water in the wrong wind direction.

If you don’t anticipate a simulated engine failure, you shouldn’t be on the ride. I was relieved we addressed that bit right away, and even more relieved to gracefully stuff it into the water, deadstick.

After nearly eight landings, it was time to demonstrate docking and ramping. Back in the office, Brown offered meaningful explanation to each of the questions I bungled and bumbled. He also offered sound advice for avoiding a litigious outcome while mixing it up with careless boaters and agitated homeowners on the water. Not everyone thinks seaplane traffic is cool, so he reminded me I was now an ambassador and an official seaplane pilot.

Down to Business

Scheduling your training slot requires a $300 deposit, deducted from the $1400 course fee, which includes five hours of dual. Each additional hour is billed at $185 per.

Brown’s five-hour dual instruction is mostly in line with the other curriculums I looked at, but its pricing certainly is not the least expensive. But, they aren’t the most expensive, either.

The place hosts an atmosphere that’s genuine with no pretentions. That’s worth a lot, as was the additional ground schooling given for gratis. Brown’s will instruct in a customer’s aircraft if there is an instructor qualified to fly it and sets pricing based on each situation.

If I had a nit to pick, it would be the inability to rent Brown’s J-3 once you have your temporary ticket and fresh FR. But as the sidebar on the following page warns, that’s not easy anywhere. Still, it’s tough to walk away without proving to yourself that you can fly a seaplane on your own, but Brown and your instructor know you can.

Contact www.brownsseaplanebase.com, 863-956-2243.