Park a later-model Cirrus SR20 nose-to-nose with its big-brother SR22 and you’ll be hard-pressed to tell which is which.

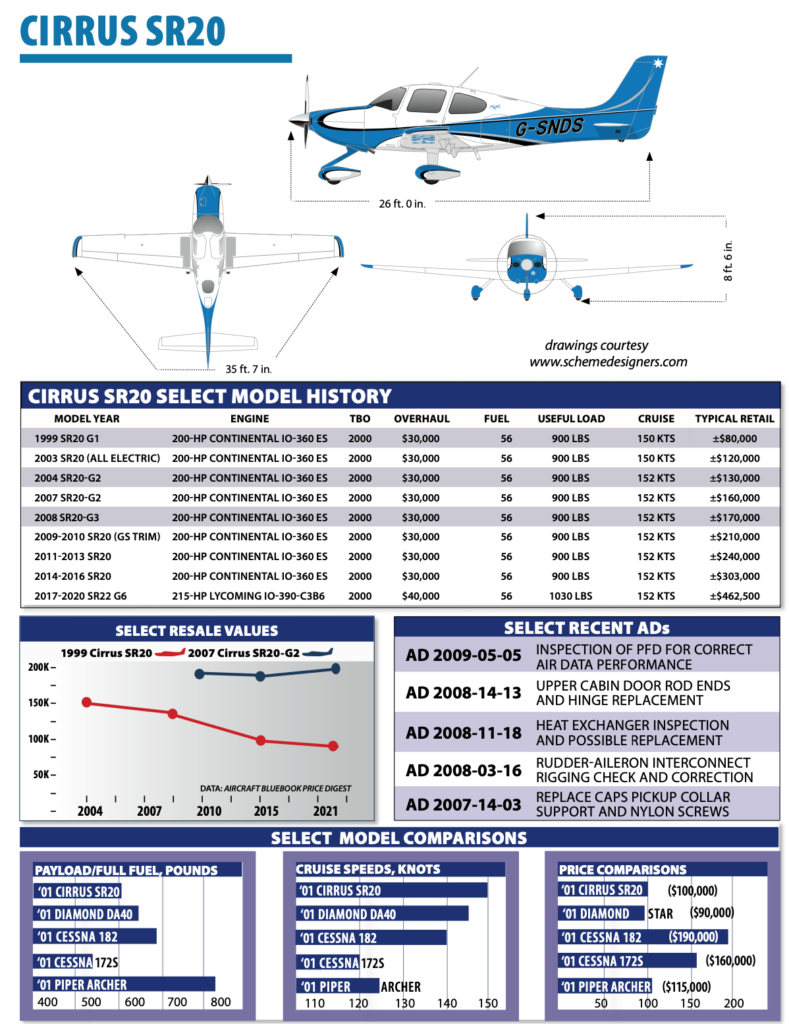

And that’s a hint for why the SR20 is a good primer for flying the higher-horsepower SR22, and for many new pilots, starting in an SR20 is the better way to move up. It may never lose its trainer title, and until recently, the SR20 has been overshadowed by the SR22. But the SR20 got a boost in ego—and performance—back in 2017 when Cirrus re-engined the six-cylinder Continental-power bird with a smooth-running and efficient Lycoming IO-390. That stretched the useful load and potentially increased the engine’s TBO.

Like most popular piston singles, resale values on well-cared-for SR20s are up. To get a fresh feel for the market, we took a close look.

MODEL HISTORY

The American success story has been told plenty of times. Cirrus Design began life offering a kit for the VK30, a composite piston-single pusher seating five. By 1993, company founders—and brothers—Alan and Dale Klapmeier announced kits were a dead end for them. Even so, they maintained that traditional airplanes from Cessna, Piper and others were too hard to fly, lacked intelligent safety features and failed to push the technological edge in both design and manufacturing. “We have to lose a lot of this macho stuff,” Alan Klapmeier told Aviation Consumer in a 1997 interview. “Making it too hard to fly is not a good value.”

What eventually became the Cirrus SR20 emerged from that philosophy and, from the beginning, was a different airplane. In addition to composite construction, its side-stick controller (really a half yoke; its movement is the same as using one hand on a conventional control yoke, not a side stick), swing-up doors and then brand-new multifunction display immediately set it apart from the traditional airplanes coming from Wichita and Vero Beach.

The most innovative detail, however, and the one garnering all the attention in the months and years leading up to the SR20’s certification, was the Klapmeiers’ insistence every Cirrus sold would come with an airframe parachute as standard equipment. Their desire stemmed from a 1985 midair collision involving Alan Klapmeier, which resulted in the other pilot’s death. Based on that experience, the Klapmeiers realized no matter how well-trained or experienced one might be, there were situations where there was nothing a pilot could do to save the airplane, himself or his passengers unless some kind of “whole-airplane” parachute was developed.

The Klapmeiers gambled the parachute would make their brainchildren stand out on the market and resolve much of the anxiety many passengers (and more than a few pilots) associate with personal aircraft. At the time, no one had proposed equipping an airplane as large and fast as the Cirrus with a ballistic parachute. Reaction was mixed, with many predicting the FAA would never sign off on the idea.

They were wrong. Cirrus worked with Ballistic Recovery Systems through a number of designs for what came to be known as the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System, or CAPS. The system exacts an 85-pound useful load penalty—and a recurring maintenance expense.

There is a six-year replacement on a pair of line cutters used in CAPS deployment that costs approximately $1500 total. That’s cheap compared to the 10-year CAPS repack, which is over $9000 in parts, plus 30 hours of labor for pre-2004 aircraft and 8 hours for later ones. The difference comes from a CAPS access panel added in the G2 revision of the design. We covered repacks in detail way back in the December 2012 issue. We also noted the depreciation of airplanes as they come up on repack time may be greater than the cost of the repack itself.

The CAPS has proven successful in our mind at what it was designed to do: lower an airplane and its human cargo to the ground, giving both a chance to fly again. To date, according to the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association (COPA), there have been 102 CAPS events in both SR20s and SR22s. COPA points to over 193 lives saved aboard the airplanes. Notably and despite lore to the contrary, deploying the ‘chute does not automatically total the airplane. One of the first deployments involved an airplane whose aileron detached in flight. The pilot escaped without injury while the airplane was recovered, repaired and returned to service. In at least two other CAPS events, the airplanes were expected to be repairable.

The FAA granted a type certificate in late 1998, and the first airplanes were delivered as 1999 models. Cirrus initially offered the SR20 in three option tiers, originally designated A, B and C, which we’ll explore in a moment. Today’s offerings generally continue that theme, with the base airplane and upgrade packages, culminating in the GTS version.

Borrowing a page from Henry Ford, customers initially could order their Cirrus in any color they wanted, as long as it was white. This lack of color choices stemmed from an FAA-imposed limitation born from a fear that darker, heat-absorbing colors would hasten the composite structure’s deterioration. As experience was gained, darker colors have been allowed. Most early Cirri come in a white or ivory base paint, with multicolored striping. Both the SR20 and the SR22 carry a 12,000-hour airframe life limit.

EVOLUTION

Among other features, the avionics in the SR20 have been through several evolutions, and the very first panels seem ancient by today’s standards. Trimble bailed out of the light aircraft avionics market before the first Cirrus was shipped and Cirrus wisely adopted Garmin for its panels. The A-spec airplanes came with a GNS 430, a GNC 250XL, an audio panel and GTX 320 transponder, plus the ARNAV ICDS 2000, a then state-of-the-art multifunction display. For autopilots, the “A” aircraft have S-TEC System 20s, upgradeable to System 30s, which includes altitude hold. All of the early aircraft used vacuum instruments, but had an electric backup vacuum pump. Rounding out the panel are analog engine and systems gauges clustered on the far right.

Meanwhile, “B” airplanes have a GNS 420 in place of the GNC 250XL, the System 30 is the standard autopilot and a Century NSD360 vacuum/electric HSI is fitted in place of a vacuum-powered directional gyro. The C-spec airplanes have dual GNS 430s, System 55 autopilots, dual alternators and a Century NSD1000 electric HSI. Options for the “B” included dual alternators, leather seats and three-blade propellers, with roughly 70 percent of SR20s being loaded “C” models.

Beginning with serial number 1268 and the 2003 model year, Cirrus did away with vacuum systems and introduced the all-electric airplane. The A, B and C designations evolved to 2.0, 2.1 and 2.2, respectively. The all-electric airplanes have dual alternators—a 75-amp main alternator and a 35-amp secondary unit—plus dual batteries. There also are two busses, a main bus and an essential bus for critical load items such as nav and comm functions and lighting.

The 2.0 airplane didn’t change much over the old A airplane except in the case of the ARNAV ICDS 2000: Cirrus switched to the Avidyne EX3000C, a higher-resolution MFD widely acknowledged as more sophisticated than the one it replaced, but—since it won’t accept external sensors such as data from a remote-mounted Stormscope—one intended for the VFR or IFR-lite pilot. The all-electric 2.0 offered a DG, but most buyers opted for the Century NSD1000 electric HSI. The 2.1 airplanes have an Avidyne EX5000C and NSD1000 as standard, while the 2.2 airplanes featured a pair of Garmin GNS 430s, the EX5000C and a Sandel SN3308 electronic HSI. Most airplanes delivered have the 2.2 package.

In early 2004, Cirrus introduced the G2 models of both the SR20 and the SR22, featuring a new door design, better interiors, a redesigned firewall for improved crashworthiness and other upgrades. Cirrus says G2 airplanes have slightly less drag and are thus a knot or two faster than previous models. Later that year, Cirrus began offering the SRV, a VFR-only model intended for the training and low-end market. It was discontinued by 2010.

For 2008, the G3 SR20 variant was introduced, featuring the wing from the SR22 G3, redesigned landing gear and a 50-pound useful load increase, among other changes. The new wing added a few knots to the airplane.

In 2012, a flex seating arrangement was introduced for the rear seat; the 60/40 split allowed room for three passengers and for the seat back to fold down in sections.

Many would-be buyers might wonder if an early SR20 can be retrofitted with a PFD or if a vacuum model can be converted to an all-electric model. Cirrus says these upgrades aren’t possible, but kits are available to replace the ARNAV ICDS 2000 with the more-capable Avidyne EX5000C, and many of the early aircraft have already had this upgrade. This change accommodates state-of-the-art options like displaying remote Stormscope and Skywatch data and incorporates EMAX engine monitoring, XM WX datalink and CMAX, Avidyne’s electronic approach plate system.

Current 2021 SR20 models (from $594,000) start with a Garmin G1000 panel using 10-inch PFD and MFD screens, dubbed Cirrus Perspective+, and then add options like larger screens, a satellite comm system and active traffic alerting.

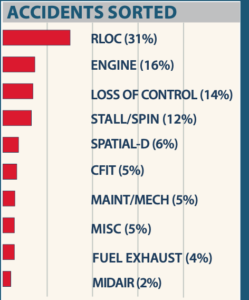

Stats from late 2019 show that landing-related accidents play an outsized role in the Cirrus accident picture. We’re not sure if the Cirrus line has the highest incidence of runway loss-of-control (RLOC) accidents, but our long-term reviews of other aircraft find that the Bonanza and Cessna singles and retracts have a lower RLOC percentage. By model, Mooneys are sometimes comparable.

What’s relatively unique about Cirrus RLOCs is that they seem to occur at higher speeds and significantly damage the aircraft. While injuries aren’t common, we found at least a dozen that did involve slight to moderate injuries and one fatality. To be fair, we found similar accidents with other types, but they aren’t as numerous.

Complicating characterizing this accident type is that many involve a hard touchdown, followed by a go-around that goes bad because the pilot fails to counter the engine’s strong torque at low speed, causing the airplane to roll and catch a wing. These are often found on the left side of the runway. Some are described as stalls.

Speaking of which, despite the Cirrus stall-resistant split-incidence wing, the type does have a stall/spin presence. A handful of these were base-to-final turns; some were on departure or on some phase of the approach.

Otherwise, rounding out the Cirrus accident pattern are the usual suspects. Loss of control is garden variety upsets in turbulence or due to pilot distraction. More than one of these was saved by a CAPS deployment and the pilot lived to tell about it. Spatial disorientation as a cause appears to be comparable to other models, but again, the CAPS saved the day in some of these, where it is nearly always fatal in other models.

POWERPLANTS, SYSTEMS

Initially (and until the 2017 model year) the SR20 was powered by the 200-HP six-cylinder Continental IO-360-ES. It was a somewhat unusual choice but one yielding sufficient power. The engine’s TBO is 2000 hours, but overhaul costs are on the high side, at about $40,000. Throttle and RPM control are done via a single lever that moves both cables. Full throttle will yield 2700 RPM. A reduction of power brings 2500 RPM, where it will stay until power is so reduced it can’t be maintained.

This is done through a cable-and-cam arrangement that works we’ll enough, but there’s no way to find an RPM sweet spot. Some owners have complained about rigging difficulties and trouble getting precise power settings. Most of these airplanes have three-blade props, but those with two-blade props (especially in the early years) may have better weight and balance numbers without a hit to performance.

For the 2017 model year (SR20 G6), Cirrus walked away from the Continental in favor of Lycoming’s four-cylinder 215-HP IO-390-C3B6. Cirrus also certified the airplane with a lightweight Hartzell composite prop (an option), which shaves nearly 30 pounds from the airplane. With the new engine (and lighter avionics), Cirrus was able to change the maximum gross takeoff weight to 3150 pounds—an increase of 100 pounds from the old airplane. With as much as 150 pounds increase in useful load (1030 pounds), you can haul around another passenger, or more of your stuff. Flap extension speed went from 110 to 150 knots.

Additionally, the new Lycoming added a layer of simplicity that perhaps didn’t exist with the Continental-powered SR20. After all, there are two fewer cylinders to worry about. As Cirrus’ senior line manager Ivy McIver told us when we first flew the re-engined SR20, “From a maintenance and operational perspective, the four-cylinder Lycoming in the new SR20 is simpler and will be less expensive to maintain just because it has fewer parts.”

A selling point for training operators is the G6 SR20’s engine TBO. For high-time usage (flown more than 40 hours per month), the IO-390’s recommended TBO gets bumped to 2400 hours. The Continental IO-360ES has a 2000-hour TBO.

With the exception of aluminum control surfaces, all SR20 airframes are entirely composite. The wing is constructed with a beefy, continuous spar. Control surfaces are activated via cable from side controllers mounted on the cockpit walls. Trim is electric only, with coolie hat buttons on each stick, a sore spot for some owners, who say they would like a manual trim wheel for backup and fine tuning.

The Cirrus wing has a stepped leading edge that’s supposed to stall the inboard section first—allowing roll control throughout—and be resistant to spinning. The airplane is not approved for spins, nor did it undergo official spin testing. If a spin develops, the first anti-spin response is roll input with ailerons, but the official response is deploying the parachute.

Cirrus airplanes are designed with crashworthiness in mind. The SR20’s fuel supply, for example—60.5 gallons total, 56 gallons usable—is stored between the wing spars and we’ll outboard of the cabin, providing significant crash protection.

The landing gear is designed to absorb energy and flex into the wing inboard of the fuel cells, thus leaving them intact in the event of a hard landing or crash. The seats are 26-G-impact designs and each has four-point harnesses with inertial reels and airbags in the front seat shoulder harnesses on newer models. If the worst does happen, the airplanes come with a crash hammer so occupants can extract themselves. One major safety feature is the lack of yokes to impale front-seaters during a head-on impact.

PERFORMANCE, ERGOS

Despite being the company’s entry-level model (and mostly used as a trainer) it’s also fair to think of the SR20 as a high-performance go-places traveler—especially later models with their refined cabin and advanced Garmin avionics. As a fixed-gear cruiser measured against the likes of the Cessna 172 or 182 or even the Piper Archer, it’s respectably fast. Although Cirrus initially claimed 160-knot cruise speeds, 145 knots for the older models to 155 knots for later SR20s is more like it. Cirrus service centers will tell you that a slow SR20 should be checked for proper rigging.

Although the SR20 is adequately powered, it’s not overpowered. At 3050 pounds for the later versions (3150 for the G6), it’s heavier than most airplanes with 200/215 HP. At moderate weights, expect 700 to 800 FPM initially, falling off to 500 FPM above 4000 feet. Given its weight and the power available, expect the airplane to be somewhat of a dog in high density altitude situations. Owners say the POH is on target for fuel burn at about 10.5 GPH for typical cruise, 9.0 GPH when lean of peak. Still-air range is about 675 miles, with 45-minute reserve, when planning to use the full 56 gallons legally available. Down-fueling to the tabs allows more cabin load, but dramatically cuts endurance to less than two hours.

Initial max weight for the SR20 was 2900 pounds but a later service bulletin, if complied with, allowed a gross of 3000 pounds. The SR20 G3, meanwhile, has a max gross of 3050. Cirrus initially claimed a standard empty weight of 1875 pounds for a useful load of just over 1025 pounds.

Not really, say some owners. Empty weights are typically 2000 pounds or more with useful loads of just under 900 pounds. With full fuel, that leaves 560 pounds for people and stuff. CG tends forward rather than aft. This requires heads-up flying, for the airplane is not blessed with an overabundance of elevator authority.

When we flew the Lycoming-powered SR20 with two aboard and tanks half full, we saw almost 1200 FPM departing the McGhee Tyson airport in Knoxville, Tennessee. The optional air conditioning system can be left on during takeoff, but you want to turn it off for max climb performance. Retract the flaps at 85 knots and enroute climb is made at full power. When it’s time to lean the IO-390, leave your Continental IO-360 procedures at home. Lycoming doesn’t condone lean of peak EGT operations. Instead, the Garmin Perspective+ onscreen leaning guidance is based on best economy, or peak EGT. When pulled back to 8.5 GPH, plan on 135 knots. Want to set best power? Enrichen the mixture to 100 degrees rich of peak EGT. At 4000 feet and 75 percent power, plan on nearly 150 knots burning 12 GPH, which yields four hours of no-wind endurance.

The SR20 really does make a good primer for someone planning to step up to an SR22. Approach and landing in the SR20 isn’t much different than in the SR22, although everything happens more slowly—that’s good for training. For us, 75 knots on short final works we’ll and like all SR models, the pitch and roll compression springs create moderate control pressure (and impressive roll and pitch stability), which means you absolutely must keep the aircraft trimmed.

The flaps have three positions: 0, 50 percent (16 degrees) and 100 percent (32 degrees), and the first notch can be extended at 150 knots. Incidentally, the Vpd—for CAPS parachute deployment—is 133 knots.

Both the front and back seats of the airplane are exceptionally comfortable by GA standards, and later-model interiors are posh. With no yoke to obstruct the view, the front seats are like flying from an easy chair, with an expansive view out the generous side windows. The side-yoke controller is easy to adapt to by using a rest provided for your forearm. It’s fair to say that the airplane generally rivals the Bonanza in handling ease, although it (like the SR22) is an autopilot airplane.

Cirrus largely achieved its goal of building a low-maintenance airplane. There are 11 ADs on the airframe, two of which relate to minor issues with the parachute firing mechanism. Initial problems with hard starting of the IO-360 and failed starters were addressed with tweaks to the fuel system. Early models had landing lights mounted on the cooling baffling in the air inlet, which caused them to fail frequently. The mount was reworked and newer models have the light in the cowling.

A search of Service Difficulty Reports discovered fewer than 20. There were only two recurring themes: cracked spinner bulkheads and chafing ignition system wiring.

Early complaints included engines eating cylinders, fuel pumps and alternators not lasting and several Garmin and Avidyne repairs. Pre-G3 era fuel gauging was criticized, and we can recommend the CiES digital fuel sender retrofit for the majority of G2 models.

Another issue, and one resulting

in AD 2006-21-03, involves the brakes. Since all Cirrus models have free-castering nosewheels, directional control at low speed is done via differential braking. Some pilots may have used the brakes to control taxi speed instead of reducing power. The predictable result: overheated brakes, leaking fluid and the occasional fire. Depending on serial number, the AD calls for a one-time O-ring or caliper replacement, plus trimming the wheel fairings and installing temperature indicators and inspection holes.

An AD issued in 2008 (AD 2008-11-18) requires a 100-hour pressure-test inspection of the exhaust systems installed on early SR20s, serial numbers up to 1815. Carbon monoxide can leak into the cabin from cracked components, potentially disabling the pilot. We’re not aware of an alternative method of compliance.

Many of the older Cirrus aircraft used vinyl designs. Vinyl doesn’t age as we’ll as paint, and so when the original base paint is still in good condition, replacing the vinyl allows the aircraft look to be renewed and updated without the cost of a full-up repainting job. Typically, repainting a Cirrus can be anywhere from $18,000 to $30,000 depending on the design and the paint shop doing the work. Replacing the vinyl kit is a considerably less expensive investment. Applied Arts vinyl kits from Scheme Designers for example, cost $1999, including custom colors and design assistance in setting up the colors, logos and tail number. Typical downtime is four days—that’s two days to remove the old vinyl, one day for touch-up and buffing and one day for installation of the new vinyl. This means that a owner can get a renewed look for their aging Cirrus for an investment of around $4000 to $6000, depending on who is doing the work. I’ve had several owners do the work themselves—removing their old vinyl design and buffing the aircraft. Some have brought in a certified 3M vinyl installer to assist in applying the kit. Other clients use a paint shop or a Cirrus service center to accomplish the work.

Sherwin Williams works closely with Cirrus, and provides most of the paint used on Cirrus aircraft. They have continued to develop more and more colors that meet the thermodynamic limitations imposed on paints used over the whole fuselage, or the whole aircraft. There are fewer colors available for use on the wings and horizontal tail (white, several silvers and a champagne gold). There are many more colors available for unlimited use on the fuselage, tail, wing- tips and wheel pants. This is giving owners more and more interesting opportunities for creating unique-looking Cirrus designs.

Nonstandard colors can be used, but there are significant coverage limitations that have to be carefully complied with when creating a design. Ignoring limitations will result in an aircraft being grounded until the offending paint scheme and/or colors are replaced. With the increasing palette of available “approved” colors, using non-standard colors is becoming less and less common.

Cirrus enforces its copyright on schemes that are four years old or newer. Owners repainting their aircraft need to ensure that they do not simply have their paint shop copy a recent factory design. The paint shop or owner can contact Cirrus to check if a design can be used or not.

—Craig Barnett

IMPRESSIVE DEMAND

As for type-club support, you can’t get much better organized than the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association (COPA). The organization maintains an excellent website (www.cirruspilots.org) with both public access and members-only forum sections. It’s an absolute must for any would-be Cirrus buyer.

If you want a pre-owned SR20 of your own, get in line. Demand for good ones is high and prices are through the roof. It seems the most sought-after SR20s are the IO-390-powered models. Cirrus sales pros are convinced that maintenance shops prefer wrenching the four-cylinder Lycoming over the six-cylinder Continental IO-360 ES. Maintain a Continental-powered SR20 and you’ll keep an eye on cylinder issues.

On the other hand, Cirrus sales pros we talked with aren’t convinced that Lycoming-powered SR20s are the cure-all. Cylinder wear is still a reality, but at least there’s only four to deal with. Still, a well-maintained Continental on the SR20 airframe is a good, smooth-running combination. Like any engine, know how to fly it.

And, source any used Cirrus from reputable sellers, and one that’s been maintained by shops versed with Cirrus. One with a tight working relationship with the Cirrus Aircraft internal sales team is Lone Mountain Aviation (www.lonemountainaviation.com). It buys, sells, trades and coordinates finance matters for only the best pre-owned Cirrus models on the market—from the SR20 to the SF50 Vision Jet. Before the program was dropped, it was one of two Cirrus Certified pre-owned dealerships. While Lone Star doesn’t just sell Cirri, it sees plenty of Cirrus step-ups and gets hands on some low-time, top-dollar Cirri.

Daniel Christian at Lone Mountain told us that SR20s sell within days (sometimes hours) on the market. Most late-model G6 SR20s sell for more money than they did when they were new, sometimes sight unseen. The G3 SR20 is also desirable, because it ushered in the Garmin Perspective G1000 avionics suite, including the integrated GFC 700 autopilot. A handful of G2 models had Avidyne Entegra glass with a stack of Garmin radios. Most early SR20s have been nicely retrofitted, and there are a variety of retrofit STCs for Garmin, Avidyne and Aspen avionics. These are often done during refurbishment projects—interior, paint/decals and engine swaps—and plenty of shops are turning out custom refurbed SR20s that rival new airplanes.

Over on the factory side, Cliff Allen, Cirrus’ Northeast sales director, sees record demand, and a current delivery backlog for new SR20s is sending buyers into the used market looking for late-model birds.

We’re told that roughly 75 percent of SR20s go to training fleets, often changing hands from school to school because many Cirrus training centers will only put new models on their flight line.

Steve Schwartz at Aerista (www.aerista.com), another respected and high-volume pre-owned Cirrus dealer (which was the other Cirrus Certified pre-owned partner), had good advice for buyers serious about buying an SR20 in a very tight market.

“You have to be in touch with the bigger brokers because they know what’s coming into inventory, and in the case of used Cirrus SR20 (and some SR22) models, they’re typically sold before even hitting the market. I’ve never seen that before,” he told us. Just because a plane is listed on Controller.com doesn’t mean it’s actually available. This kind of feeding frenzy has jump-started aircraft acquisition services. Think about it. If a buyer is paying for an acquisition service they’ll likely be the first to know when an airplane is about to come on the market.

And since the pre-owned Cirrus market is so tight, if you snooze you might lose. “Be ready to go—have your financing and insurance in order because when that airplane hits the market you have to be ready with an offer,” Schwartz said.

The buyer can have an advantage. The way many used aircraft contracts are set up is a buyer can lock in by making an offer and if it’s accepted, go into contract and send a deposit into escrow. The right contracts are drawn up so that the deposit is fully refundable, so you can sit on the airplane until you have to make a go or no-go buying decision. Make sure you have an out.

To give you an idea of what a good SR20 looks like on the market, at press time Aerista was listing a 2016 SR20 G3. It’s equipped with air conditioning, Garmin Perspective avionics with ESP, synthetic vision, active traffic alerting and an extended warranty. It has 1185 hours total time on the airframe and on the Continental IO-360-ES. Its last annual was completed at the Cirrus factory service center in Knoxville, Tennessee, and the CAPS repack isn’t due until January 2026. The asking price is $379,900, and likely sold.

Here’s the thing, and it’s something that more than one Cirrus sales pro pointed out. That same money can buy a normally aspirated 2012 SR22, according to Aircraft Bluebook, which suggests a $360,000 retail price. For many, the SR22’s bigger engine makes the buying decision easier. On the other hand, low-time (and aging) pilots may likely deal with the insurance squeeze, and might only get a policy for the lesser-powered SR20. Again, secure the insurance before making any deals.