By all measure of logic, the Cessna 182 should have passed out of production years ago. Given its horsepower, its slow and in an age of $5 avgas, its hardly economical. It handles like a truck. But its that truck part that explains why, in 2008, Cessna sold 223 new Skylanes, making it essentially tied with the Cessna 172 in sales popularity. Sales tanked in 2009, but that was true for the entire market. Still, in the teeth of a vicious recession, the airplane retains relatively good values on the used market, although not many are selling. The reason for this, we surmise, is that the 182 will haul about anything you can throw at it, it has good dispatch reliability and hardly any handling, except for nose-first landings. All that adds up to one thing: Buyers are comfortable with Skylanes and for many, its as far up the pecking order as theyll go in their flying careers. These days, you can buy a 182 with a full G1000 glass panel and a luxe interior for a price in the low $400s. A big investment, to be sure, but less money than a new SR22 from Cirrus.

Model History

Wind the clock back to 1956 to reach the beginning of the 182 evolutionary history. The fact that ii looks like a giant Skyhawk which itself looks like an inflated 150 shows that Cessna just did what it does best: It built on its experience with previous designs and scaled them up.

The 182 evolved from the 180 taildragger, so Cessna added the tri-gear, redesigned and relocated the exhaust and reworked the fuel vent system. Wet wings were used to hold fuel.

With the new gear, the 182 developed a nose heavy tendency and Cessna never did sort this out.

Even new ones require deft trimming or the lazy pilot risks smashing the nosegear into the runway and crow hopping down the strip. Its not unusual to see an older 182 with repaired gear and firewall due to a nose prang.

When the airplane appeared in 1956, the average price was just under $17,000. Thats equivalent to about $132,000 in 2010 dollars. Obviously, given the price of the 182T, aircraft prices have far outstripped inflation.

In the first 182s, power was provided by a 230-HP Continental O-470-L an engine that proved to be such a worthy choice that

some variant of it was retained until the airplane went out of production in 1986. The engine remains easily overhaulable, for prices under $30,000.

With its straight tail and windowless back, the original 182 looks like an antique, but Cessna soon sleeked it up with a rakish tailfin and the classic rear window everyone loves. Gross weight was 2550 pounds, compared to the modern Skylane max takeoff weight of 3110 pounds. (More on that later.)

Cessna embarked upon a continuing improvement program, introducing new model designations every couple of years. The 182A saw redesigned gear with a wider track and a lower stance, with the mains 4 inches shorter and the nose gear 2 inches shorter. The 182A got an external baggage door and a 100-pound higher gross weight.

In 1958, the Skylane name was applied-prior to this, the airplane was simply called the 182-and a deluxe version with wheel pants, standard radios and full paint instead of the trim-over-bare aluminum of the basic 182.

The 182B, with cowl flaps, came out in 1959. A swept tail was added in 1960 to make the 182C; it was basically a styling move, since the swept tail degraded spin recovery and reduced rudder power. The gear continued to be a bit of a problem, so in 1961, it was lowered again, by another 4 inches, on the 182D.

As it did with other models, Cessna put a rear window (Omni-Vision) on the airplane in 1962, with the 182E. This airplane was a significant upgrade over the earlier 182s and these are often thought of as “modern” Skylanes. The fuselage was widened 4 inches and the cabin floor lowered by 3/4 inch to make more interior room.

Electric flaps became standard, the panel layout was updated and the adjustable stabilizer of the original gave way to a trim tab. The gear was beefed up (again) and the gross weight was boosted to 2800 pounds. A different engine variant, the O-470-R, was fitted. The 182E also had a redesigned fuel system, with bladders and the availability of auxiliary fuel which raised capacity to 84 gallons.

Cessna also made changes that werent as obvious. To save weight, it used thinner aluminum for the skins and converted from sheet aluminum to roll aluminum, which was cheaper. That also yielded an airplane with more surface imperfections, which ended the days of polished metal airplanes. Full paint jobs became standard, to hide the dimples. The new airplanes were only 10 pounds heavier than the old ones but performance actually suffered, with reduced climb, takeoff performance and service ceiling.

The 1963 182F sported a thicker, one-piece windshield and back window, a standard T-panel and an increase in horizontal stabilizer span of 10 inches. Flap pre-select also became standard. From the F model forward, until the S arrived in 1997, changes were less dramatic. The G model had an available kiddie seat for the baggage bay while the 182H got an alternator to replace the generator.

Turbocharging

The next significant upgrade was with the 1970 182N model. Gross weight was increased to 2950 pounds and the spring-

steel gear was swapped for tapered tubular steel legs that allowed more fore-and-aft movement.

Track was widened again, to 13-1/2 feet, improving ground handling somewhat. In 1972, a leading-edge cuff was added to the wing to improve low-speed handling, resulting in the 182P, a variant that stayed in production through 1976. The dorsal fin was extended and the cowling was shock mounted.

In 1981, the 182R got another gross weight boost to 3100 pounds, and an increase in standard fuel capacity, to 88 gallons, stored in wet wings. The bladders, which had been a problem, were dropped in 1978. Cessna also switched over to a 28-volt electrical system. A turbocharged version was added to the line in 1981, the T-182RII, powered by a Lycoming O-540 producing 235 HP. Production ended in 1986 with the 182R.

New Era

In 1997, when Cessna re-entered the market, it introduced a newly retooled Skylane for the next century. The changes were substantial, some cosmetic, some not. The biggest change was dropping the reliable O-470 for a 230-HP Lycoming IO-540-AB1A5; no surprise there, since Cessna and Lycoming share the same parent company, Textron.

But the change improved one thing. The O-470s were quite susceptible to carb icing and the injected Lycoming solved that. But like the O-470, the Lycoming is a bit of a fuel hog. Further, the Lycs are known for lunching cams at the mid-time point, which the TCM engines don’t typically do. Also, the Continental is a smoother-running engine, in our view.

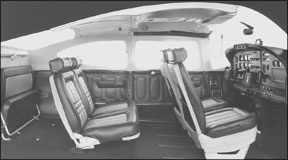

Cosmetically, Cessna did away with the old Royalite instrument panels, replacing them with painted metal. The interior-seats and cabin panels-is much improved, as is the instrumentation. Interior surfaces are now treated with epoxy-based anti-corrosion materials.

The latest 182 also has sealed wet wings, not bladders, making us wonder if owners will encounter leaks as the sealants age, as happens to Mooney owners. To get water out of the system, the airplane has no fewer than 12 separate drains, five on each wing tank and two at the bottom of the cowling. Although gross weight of the airplane is 3100 pounds, its typical empty weight is substantially higher than earlier models so it carries less than, say, an early 1980s RII. Speedwise, the normally aspirated model is respectable, cruising at just under 140 knots on 16 to 17 GPH. One reader told us the turbocharged 182 is capable of the mid-160 knots in the teens.

Maintenance wise, the 182S has proven the target of a number

of Cessna service bulletins, with most of the work being covered under warranty. Thus far, weve heard no significant beefs related to unusual maintenance problems.

Market Survey

The market may have been more we’ll delineated when the 182 appeared but its a jumble now. There are so many used and new airplanes available, its hard to know what to compare the 182 to. The Skylane still offers lots of interior space and an unusually flexible payload/range combination that explains its enduring appeal. Late-model Skylanes have depreciated to the point that a 1997 S model can be had for $135,000 or less. Thats a good value when you consider that one 10 years older-a lesser airplane, in our view-sells for half that.

For equivalent capability, buyers may or may not favor Cessnas over Pipers. An average-equipped 1979 Skylane will fetch about $71,000 while a 1979 Piper Dakota has held its value, bringing as much at $109,000, despite the fact the Cessna cost less when new. Since our last Used Aircraft Guide on the Skylane, that price Delta has opened up a little.

Which Skylane model? That depends on budget. As noted, the latest models have started their depreciation slide and are looking to be better values than ever. These are well-equipped airplanes and are quieter and more comfortable than the earlier Skylanes. For a real steal, look for 2005 models with G1000 suites for prices in the mid-170s or less.

If youre going older, most buyers seeking a practical, use-it-often airplane wont want a museum piece, so that argues for a 182E or later. If your budget allows up to $90,000, the 1981 T-182 strikes us as a better combination of speed, value and hauling ability than any other airplane we can think of.

Performance, Handling

If fast is your mantra, the Skylane wont be your airplane. Flogged to the limit, these are 135-knot airplanes but more like 130 knots burning about 12 GPH. Range varies with year and tankage, of course, but typically, you can easily fly 900 still-air miles in the 88-gallon versions. Thats more endurance than most owners can muster.

Skylanes are prized for short and rough field ops and deservedly so. Long time reader David T. Chuljian flogs his L-Model Lane into the Idaho outback with good results.

The prop is we’ll clear of the ground and the gear is high enough to keep antennas out of the muck. If need be, the wheelpants can be removed. But still, it aint no traildragger.

The nosegear will take some hits on rough strips.

A late-model 182 will get over a 50-foot obstacle in only 1115 feet; add a third more for safety margin and youre still comfortably under 2000 feet. Initial rate of climb is good, thanks to the high horsepower but it was better in the early models than the later ones, thanks to significantly higher gross weights.

But later models-the 182P and forward-have greater fuel capacity and higher gross weights and thus offer more loading/range flexibility. This, more than any other factor, makes the Skylane a first choice as a family airplane. Its not much good to blaze along at 160 knots if you can only carry three people.

Although the CG range in the 182 series is adequate, the airplanes tend toward forward CG; ballast or bags in the baggage compartment help. Speaking of which, the baggage compartment is large and easily accessible through an exterior door. (The seals, when old, may leak and should be replaced.)

Handling? Were not talking a Miata here. The 182 is a big, stable airplane and it takes some effort to break it loose from anything other than straight and level. And even if you do, its draggy profile means that speed builds slowly enough that only a somnambulant pilot could lose it in a dive. The Skylane is heavy in pitch, so timely trimming is a must, especially prior to or during the landing flare. Get lazy in the flare and the Skylane can slam the nosegear onto the pavement, buckling the firewall and leading to a huge repair bill. Roll forces in the 182 are nothing unusual; think of a Skyhawk with stiff cables. In a turn, the Skylane will want to overbank if left alone but so slowly that you should never get behind it.

As far as roll trim goes, fuel load and balance are important in

the 182, particularly in airplanes with long-range tanks. The fuel system will self-siphon between tanks if the airplane is not parked on a level surface, so its possible to have an imbalance that wont improve in flight. Even Cessnas excellent L-R-Both fuel selector wont prevent the tanks from draining at different rates unless a single tank is selected.

Transitioning from a Piper or smaller Cessna to a Skylane is a Ralph Kramden experience: Youll definitely feel like a bus driver, albeit a regal one. The seats are high and upright and relatively comfortable. Although visibility is good forward and out the windows, the panel and glareshield are tall, requiring short pilots to use a booster seat. Heating is good for the front-seat passengers, less so for the rear. Wing root vents provide plenty of ventilation but also leak air during the winter, leading some pilots to tape the inlets. Cessna fixed this in the newest Skylanes, which are tight, quiet and warm.

Engine, Maintenance

In all of general aviation, there are perhaps a handful of engine-airframe combinations that are nearly perfect. The 182/O-470 pairing is one of them. Four variants of the engine were used, the L, R, S and U. The S (1975-76) has been the most troublesome because of its revised piston ring configuration, intended to cope with the introduction of low-lead fuel. The U variant (1977-on) is desirable because of a 2000-hour TBO, though earlier engines are upgradeable from their 1500-hour TBO. Its a rare Continental that makes it to TBO without some form of top overhaul but as big displacement engines go, the O-470 is more likely than most to get by without a top.

Because of its high population and simplicity, the O-470-series is relatively inexpensive to overhaul. One persistent weakness of the design, however, is the tendency of the carburetor to ice up. In carb ice conditions, you have to be on your toes in using carb heat-the accident history shows this.

In its singles, Cessna wisely adhered to the KISS theory for the fuel system. But early models still had their problems. The

bladder fuel systems found on 1962 to 1977 Skylanes didnt fit we’ll in the wing bays, resulting in the possible formation of a diagonal wrinkle across the bottom of the bladder. Combine that with water leaks due to deteriorated O-rings in the flush fuel caps and you can see the problem; the wrinkle acts as a dam to trap water that the pilot couldnt remove during pre-flight sumping. On rotation, the water would spill over the wrinkle, reach the fuel pick-up and choke the engine on climbout.

The FAAs response (AD 84-10-01) was to mandate the installation of additional drains and the inspection of the bladders for wrinkles. This is better known as the “rock-and-roll” AD, for it also directed pilots of airplanes not so modified to go out to the wingtip and shake it up and down to get the water to slosh over the wrinkles. This Marx Brothers-like procedure is certain to cause serious doubt in the minds of nervous passengers.

Otherwise, the Skylane is relatively free of serious ADs. A few have cropped up recently, but theyre one-time directives. 98-1-14 calls for replacement of mufflers; 98-1-1 mandates inspection and possible replacement of the alternate static air valve. Also of note are 97-21-2, inspection of certain cylinder installations, 97-15-1, replacement of specified cylinders and 96-12-22, recurrent inspection of the oil filter adapter.

More recently, Continental had issues with valve lifters coming apart and these impacted some O-470s. On page 25, weve published a summary of ADs against the S-model Skylane. Although the number is seemingly large, none are especially onerous.

Mods, Clubs

The Skylane may hold the record for having the most modifications available and many of them are good. The big

ticket items are engines, replacing the stock O-470 with a Continental O-520 or IO-550, another TCM product with a good reputation. P.Ponk does the 520, contact pponk.com or 360-629-4812. Peterson Performance Plus (316-320-1080) offers an impressive STOL package and O-470 engine upgrades.

Air Plains (airplains.com, 800-752-8481) does O-520 and O-550 conversions for the Skylane. For another STOL package, see Sierra Industries at sijet.com or 830-278-4481. Texas Skyways offers the O-550 upgrade; check them out attxskyways.com or 830-755-8989.

In the June 2001 issue of Aviation Consumer, we reviewed the Horton Flight Bonus speed package; contact 800-835-2051 or stolcraft.com. More speed mods are available from Knots2U at knots2u.com or 262-763-5100 and Maple Leaf Aviation at 204-728-7618 aircraftspeedmods.ca. Met-Co-Aire has drag reducing wingtips; see metcoaire.com and phone 800-814-2697.

If you want to slow down instead of speed up, contact Precise Flight (preciseflight.com or 800-547-2558) for a speed brake kit. Vortex generators are available from Micro Aerodynamics at 800-677-2370 or microaero.com.

If six hours of endurance isn’t enough, see Monarch Air and Development for aux tanks and improved fuel systems. For more aux tanks, see Flint Aero (flintaero.com and 619-448-1551) and O&N at onaircraft.com or 570-945-3769. Last, don’t forget props from Hartzell; three-blade conversions are available. See www.hartzellprop.com or 937-778-4200.

There are a couple of Cessna groups. We highly recommend the Cessna Pilots Association, 805-922-2580 and on the Web at www.cessna.org as the first stop in obtaining information before purchasing a Skylane. These guys have been at it for years and know the brand well. Find more support at the Cessna Owner Organization at 888-692-3776 or www.cessnaowner.org.

Owner Feedback

I have owned my 1968 L model Skylane since October, 2000. I had been flying a Cardinal RG into the Idaho back country and I was getting tired of repairing the landing gear all the time. The engine was a zero-time field overhaul, with chrome

cylinders and has generally behaved well; I figure replacing a cylinder every 600 hours is par for the course for the O-470-R.

Ive had many and varied problems with the mags, including left/right failures within two hours of each other. I replaced the nose fork with the 206 style with the 6.00-inch tire and put 8.50s on the mains for better back country durability. Eventually went with 26-inch tundra tires. In spite of this, I spent several thousand dollars repairing extensive firewall and nose floor damage a few years ago-its still not a tail dragger.

The tundra tires were disappointing, as they cost $4000 and wore out after just a few years-my flying is mostly on pavement nine months of the year. The 206 fork/wheel cost about 7 knots and the tundra tire conversion (which put an 8-inch tire on the nose) took another 12 off that, so my 182 was flying at 115 knots at low altitudes, although the speed penalty was not too bad above 8000 feet. I removed the back seat and put in one F. Atlee Dodge jump seat, spiffed out with Oregon Aero foam, so now I have a three-place 182. I have never ridden back there, but passengers tell me its not bad.

One thing my 1968 lacks is decent baggage space; the very early models have an extension by STC, and later models came with an aft cut-out. I installed a Garmin audio panel and GNS530W and an engine analyzer. I have two glideslopes for IFR flying.

About the time I bought the airplane, gas prices went up enough to make flying to Idaho and Montana for weekend camping trips fairly expensive, so now I mostly use it to commute to Seattle on weekends and around the state. Once a year I take it up into the Canadian subarctic, laden with inflatable kayak and gear for a two-week solo trip. The Canadian trip is the reason I keep it rather than opting for a 172, which wouldnt quite carry everything. Total expenditure over nine years was $184,000 for 1200 hours-includes hangar, insurance, avionics upgrades, everything but engine and prop reserve-and both are pretty much run out. This year I quit keeping track of the costs. Its too depressing.

Ive attached photos, one showing how much you can fit into a 182, another showing the tundra tires (sealed up with tape to keep three weeks worth of dust out, plus some creative tiedowns).

David T. Chuljian

Port Townsend, Washington

I purchased my 2007 Skylane shortly after finishing my pilot training. I had about 100 hours in a G1000-equipped Skyhawk and I wanted to purchase an airplane that would last me for a few years, but provide for an easy transition.

The Skylanes cockpit layout is virtually identical to the 172 Skyhawk, with the addition of the constant speed prop control and cowl flaps. The 2007 production year marked the first time that Cessna included the GFC700 autopilot in the Skylane G1000 suite and so this also provided the opportunity to learn a new piloting tool, albeit one that was far more intuitive and useful than the Skyhawks KAP 140.

In almost every respect, the Skylane is easier to fly than the Skyhawk. Its 235-HP Lycoming engine provides more than enough power for short field and fully loaded takeoffs. An exception is the degradation to performance on hot, humid, high density altitude days. As I fly exclusively on the East Coast, I opted for the normally aspirated engine, but I can see how valuable the T182T would be in the high country and desert Southwest.

The Skylane is extremely stable in cruise. Steep turns, climbs and descents are very predictable. It is difficult to stall this airplane and it would take a desperation yank on the yoke (if boxed in a canyon, for instance) to provoke a stall. The stall break is gentle and responds immediately to aileron, rudder and throttle inputs.

Where the Skylane diverges in flyability for the new pilot is the landing phase of flight. The big six cylinder has oodles of power, but also makes this airframe quite nose heavy, particularly with 20 or 30 degrees of flaps and speeds under 70 knots.

My Skyhawk training never really included the use of the yoke mounted electric trim, as the usual landing sequence involved cutting power a hundred yards short of the runway and coasting in with minor hand adjustments to the elevator trim.

The Skylane requires deft and regular use of the power trim and a wee bit of power all the way into the flare. Premature throttle cut off causes the Skylane to nose dive and can lead to three-point bounced landings.

Speed bleed-off on short final is far more pronounced than on the Skyhawk, so keeping the speed at 70 knots over the numbers will provide a flare speed of 60 + knots-just enough to keep the nosewheel up, but also allow for full command authority. Flap settings of 10 or 20 degrees allow for very short roll outs, but the 30-degree setting sets up a more challenging power management scenario.

The Skylane is very rugged and forgiving, with stout main landing gear and gas-filled strut for the nose gear. Because the big Lycoming can be thirsty, I usually cruise at 21 to 22 inches MAP and 2200 to 2300 RPM. This produces a burn rate of 11 to 11.5 GPH with TAS of 125 knots. Max cruise speed at 24 inches and 2400 RPM burns 14 GPH and 135 to 145 knots, depending on altitude.

A big plus for the Skylane is its 87-gallon capacity. I have flown from Boston to Sarasota, Florida with only one stop and with plenty of reserve in the tanks. With full fuel, it leaves 600 pounds for pilot, crew and belongings.

Annuals run between $2000 and $2500 and insurance with a hull value of $250,000 and $1 million liability is $2016. I fly about 220 hours per year (VFR) and have had no maintenance issues or squawks. The Skylane is a rugged and dependable aircraft and is we’ll suited to a novice flyer.

Ray Hamel

Wellesley, Massachusetts