When modern aerodiesel engines made their surprise appearance at the Berlin Airshow in 2002, the numbers didn’t add up once the costs ultimately came to light. The engines were certainly economical, but they were twice as expensive as gasoline engines, had half the TBOs and required pricey gearboxes and other components at short-run hours intervals. A decade and a half later, these automotive-based engines may finally be turning a corner of sorts, with the announcement by Continental Motors last spring that its CD135/155 series engines will have replacement intervals increased to 2100 hours from 1500 hours.

Although this dramatically improves the operating economics of diesel engines against their gasoline counterparts, it’s not yet clear if that will be enough to expand the market much. Initial indications based on our interviews are that it will not, at least for the short term, simply because new airplanes are so expensive and conversions similarly require large investments.

By our calculation, diesel currently has a 10 percent niche in the piston general aviation market, with most of that belonging to Diamond Aircraft. Other new product entries, notably Piper’s Archer DX, haven’t found overwhelming market success, even in Europe, where diesel engines in general are more of a mainstay in the transportation system than they are in the U.S.

In this analysis, we’ll examine the details of how Continental’s longer replacement cycles impact operating economics and add a glimpse of how they compare to Austro, Continental’s main competitor.

Long Road

When we reviewed the then-new diesel-powered DA42 in 2005, the Thielert Centurion engines had but a 1000-hour life limit and the company was sketchy on replacement costs. Instead of a TBO, the engines would have to be replaced (TBR) and they also required expensive gearbox overhauls at 300-hour intervals, plus alternator and fuel pump replacements. We were assured that within a year, the TBR would reach 1200 hours and the gearbox intervals would also increase. Shortly thereafter, 1500-hour TBRs were promised. It didn’t happen.

We’re not quite sure why, but by 2008, Thielert had fallen into bankruptcy and engineering and development work came to a halt. Continental acquired Thielert in 2013 and although it infused capital into the business, it took another three years to bump the engine TBRs to what had been promised more than a decade ago. What took so long?

“I think it was an engineering mindset and a regulatory caution,” says Rhett Ross, CEO of Continental. “When we acquired them, there was a level of a confidence in the engine, but there were some technical changes that had to happen. We had to change some components to beef them up. Actually, the engine as designed could have run out to the currently announced TBR, but you’d have had a higher risk of problems and maintenance issues,” Ross adds.

With more than 3300 diesel engines manufactured, Continental certainly had the fleet data to support the higher TBRs, but it still had to jump through EASA regulatory hoops to gain the formal approvals. The new, longer-life engines themselves have some improved components, but are essentially the same as the improved Centurion 2.0 Thielert introduced even before its bankruptcy.

The Numbers

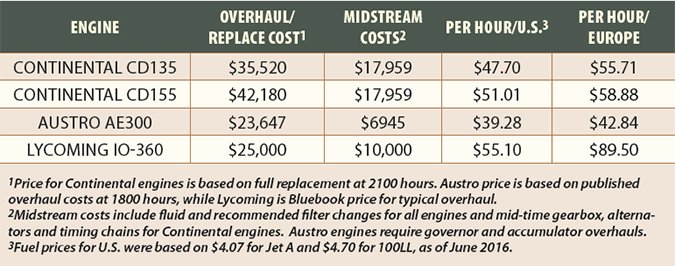

The chart at right summarizes the changes. For all engines shipped after about December 1, 2015, the approved TBR increases to 2100 hours from the previous 1500 hours for the CD135 engine and 1200 hours for the higher-output CD155 that finds application in the Piper Archer DX and the announced Cessna 172TD. (“Announced” is the operative word because Cessna isn’t promising delivery dates.)

Ross said the larger TBR leap on the CD155 was a deliberate part of the program because Continental didn’t want to incrementally increase replacement intervals by 200 or 300 hours a pop, as Thielert had done.

“We did good homework on this to get there. What we did was to build a roadmap for future actions of this type. Right now, we’re looking at improvements in line-replaceable units and we’re concentrating on the CD300,” Ross said. The CD300 is a 310-HP Mercedes-based six-cylinder engine that Continental announced two years ago. Certification is expected by early 2017 and Continental has revealed at least one minor OEM (Stemme), but no mainstream companies have announced or even hinted at new diesel-powered aircraft.

Line-replaceable units are the gearbox, the fuel pump, the alternator and the timing chain. Under the new maintenance schedule, all of these have 1200-hour replacement intervals, up from 600 hours. That means they’re basically required at mid-time and at exchange rates current in July 2016, these items totaled about $3656, a substantial decrease from the previous requirements. As shown in the chart, when other items are added, the CD-series engines require additional service items beyond the major gearbox change. When all of this is taken together—including oil and fluid changes—the engines require $18,000 in care and feeding on the way to TBR or about $8.60 per hour at current post-Brexit exchange rates.

The core engine replacement itself is currently priced between $35,520 and $42,180, according to Continental. Adding it all up, including oil changes and other required replacement items, yields a total direct operating cost of $100,430 for the CD135 or $47.70 per operating hour using data provided by Continental and a Jet A average price of $4.07 a gallon in the U.S. as of summer 2016. The CD155 is higher by an amount equal to its engine cost Delta against the CD135 for a to-TBR cost of $107,080 and $51.01 per operating hour.

The closest direct comparison is the Lycoming IO-360 or perhaps the O-320 used in the Cessna 172, a competitor in the core training market. These engines are significantly less expensive to overhaul and maintain mechanically on the way to replacement, but they also burn more fuel that’s also more expensive, especially in Europe.

The Lycoming overhaul market is far more competitive than the diesel replacement market is, but by our calculations, the IO-360 will burn through about $111,000 on the way to its 2000-hour TBO, to include oil changes and $2000 in mid-stream maintenance. If the engine requires a top, and some do, then add another $8000 and the hourly costs work out to between $53 and $59 per hour.

If that doesn’t look like a huge difference against the diesel, you’re not the only one to notice. Three shops doing diesel conversions we spoke to observed that cheap fuel prices in the U.S. are keeping conversions and even new OEM diesels from gaining a foothold. “Cheap” here is relative. While avgas prices are down considerably from two years ago, the national average price as of early July was $4.70, according to airnav.com. Jet A is cheaper, at about $4.07.

Market Realities

While the new higher TBRs for Continental diesels significantly improve their operating economics, it may, in the end, make little difference in market penetration. We spoke to three companies doing diesel conversions using the CD135 engines and none were particularly bullish that longer TBRs will nudge loose latent demand.

Even Continental’s Ross is realistic about the market. “It’s not easy making money in the aviation segment now. We’re seeing deferred fleet orders and it’s not that they’re running bad businesses, it’s just that the confidence isn’t there,” Ross said in an interview in late June. “Where I see the volume coming from is when the international market opens up and starts buying a lot of airplanes,” he adds.

That demand might come from Asia, but thus far, China has proven to be somewhat of a disappointment. Every major manufacturer has in place a China plan, but the country, despite strong potential, still has fewer than 3000 general aviation aircraft, almost all of them used for training. Ross said Continental has about 200 diesel engines operating in China and although usage is very high, fleet expansion is not.

Diamond Aircraft continues to be the leading OEM in diesel. Of 144 aircraft it shipped last year, about half were diesel, powered by the Austro 300 series engines Diamond developed on its own after a tense divorce from Thielert. Last year, Mooney announced the M10 series trainers, which will also have Continental diesels and although Ross says other companies have diesel projects in the works, he declined to offer any details other than to say there may be announcements later this year or early next.

Meanwhile, the aftermarket conversion business remains anemic. Recall that three years ago, just after Continental bought Thielert, Redbird Flight Simulations introduced its RedHawk trainer, a diesel refit of vintage 172s. Thus far, it has sold 14, which we would call moderate success. But as of early July, it has no more orders in the pipeline.

“We have proposals out waiting on signatures, but everybody just seems to be sitting on their hands,” says Jerry Gregoire, CEO of Redbird. “The RedHawk is great airplane, but a quarter of a million dollars is a lot of money. I wish we could build them cheaper, but I’m not 100 percent sure it would make a difference right now. I think we’re headed for a rough couple of years in GA,” he adds.

We heard a similar story from Premier Aviation, a Ft. Lauderdale sales and mod house with a well-established upper-tier clientele. Premier developed its own diesel conversion of 172s similar to the RedHawk project. “Sales have not been good for us. I don’t know what to make of this market,” says veteran sales executive Fred Ahles of Premier. He said that when Premier planned the project three years ago, the price difference between avgas and Jet A made it a mathematical no brainer. “No one should be flying a gas trainer today, but capital isn’t there,” Ahles says. When we asked Ahles if he sees a market turn ahead, the response wasn’t encouraging: “Tell me what the price of fuel is going to be and I’ll have an answer.”

Down the coast from Premier Aircraft, Africair has had good success selling diesel-converted 172s on the African continent for use as airline trainers. To date, according to the company’s Travis Tinsey, about 75 have been placed. And while he says the recently announced higher TBRs are a strong plus in the market, he has no illusions about a quick market bump.

“There’s been no increase in business yet because the program is too new,” Tinsey told us in June. For Africa, where avgas is scarce, the diesel economics were already slam dunk. The buyers don’t need convincing, they need more training activity. For the U.S., he says, diesel remains a hard sell.

“There’s just not enough difference between avgas and Jet A prices to make it attractive yet. The new TBR may make a difference, but the conversion is still almost $100,000,” Tinsey said.

As Continental’s Ross said, the company’s best hope for higher volume in the diesel market may be training fleets in the international market. If that’s coming, it’s not in sight yet and it’s not clear what market trends will make it happen.