If you were a dedicated Cub aficionado and wanted to build yourself the ultra version of the essential Cub idea, what would you do? You’d start with the basic planform, update it with edge-of-tech materials and build methods—carbon fiber, CNC-cut parts, modern avionics—all buttressed with an aerodynamic makeover to tweak performance. Then you’d send the airplane to the place that designs and builds seats for Bentleys and Ferraris and tell them to go wild.

And that, conceding a bit of editorial license, is the idea behind Cub Crafters’ new XCub, a full-up new Part 23 airplane that the company claims will raise the bar on the stalwart utility airplane. In fact, Cub Crafters, with the XCub, is borrowing from the automotive world and christening the new aircraft as a sport utility airplane.

The XCub’s DNA goes back to the same Piper Super Cub that Cub Crafters cut its business teeth rebuilding beginning in 1980. Not too surprisingly then, the XCub has a half-ton useful load and dainty slow-speed habits, but quite surprisingly it also has 140 MPH cruising speed and multiple-state range with the cabin stuffed full of whatever you can get into it.

The price of this no-compromises retooled Cub will initially be $297,500, with a short options list that might inch that a bit above $300,000. As the airplane’s product roadmap unfolds, Cub Crafters president Randy Lervold says the sticker may reach into the $320,000s. The company has a file folder full of eventual upgrade ideas, including floats, bigger engines and, eventually (we hope), IFR certification.

Where It Comes From

It’s fair to call the XCub a derivative of the Carbon Cub LSA, which is itself a cousin of the original Piper Super Cub. But the XCub so stretches the original Super Cub basis that it’s also fair to consider it nearly a clean-sheet design. Cub Crafters’ expertise extends to 1980 when owner Jim Richmond began repairing and rebuilding the PA-18 to serve the utility aircraft trade, much of it centered in Alaska. The business was then in and remains headquartered in Yakima, Washington. CC’s first certified airplane was the Top Cub, which is essentially an updated Super Cub. That TC has since been sold to Chinese interests, although CC still builds it under license. In 2006, the company entered the light sport market with the Sport Cub, a lightened version of the Cub airframe with a Continental O-200. That airplane morphed into what became the Carbon Cub, when CC was fishing for a new name following a trademark dispute over the Sport Cub moniker. Thanks to a 180-HP ASTM O-340 engine, the Carbon Cub claimed, at the time of its introduction, the best short-field performance of any LSA. The competition has since closed the gap (mostly), but the Carbon Cub remains a strong seller. Shortly after its introduction, the company conducted a paper exercise to explore certifying the Carbon Cub under Part 23. “We figured it would take two years and a million dollars,” says CC’s Lervold. “We missed that grossly,” he adds.

Lervold attributes the expansion of the project—it took six years and multiple millions—to a “textbook case of scope creep.” As is true with so many airplane projects, perfection became the enemy of good enough. “Instead of leveraging what we did in the Carbon Cub, we’ve taken the technology base and created a whole new one. That will sort of trickle back into the rest of the line for years to come,” Lervold told us in an interview in Yakima in early May.

The design brief was to take the basic Cub planform as far as it was practical (and economical) to go, using modern materials and production methods. CC wanted more speed out of the basic airframe while retaining the Cub’s inherent low-speed manners. It eschewed the spartan ethos traditionally applied to the interior and accommodations and pursued a standard closer to that found in a European sports sedan.

Structurally, the XCub has the same basic size and shape as the Carbon Cub, but it’s as much as 300 pounds heavier. It’s 3 inches higher than the Carbon Cub on standard gear. The typical Carbon Cub empty weight is about at the LSA limit of 917 pounds, while the empty weight of the XCub is 1212 pounds. John Whitish, CC’s marketing director, said that this weight might yet be nibbled back, but the airplane’s useful load against a gross weight of 2300 pounds is at least 1088 pounds.

What’s with the additional weight? “Structure,” says Lervold. To meet Part 23 requirements, including float loads, there’s simply more of it throughout the airplane. On the shop floor, he showed us the difference between the XCub’s vertical fin and that on the Carbon Cub. The X has a dorsal in front of the vertical fin and an aerodynamically shaped leading edge that the Carbon Cub lacks. It’s there to keep the airflow attached to meet certain envelope requirements in Part 23. However, Lervold said he’s noticed the improved fin results in less tail wagging in turbulence. Less to do with weight, but the XCub rudder horn is also smaller. In addition, the Lycoming O-360 used in the XCub is heavier than the CC version of the Titan O-340 mounted in the Carbon Cub, plus the X has a Hartzell composite constant speed prop and the associated governor and quadrant, which add yet more weight.

Also bumping up the weight is a new spring-aluminum gear design, replacing the Cub’s traditional X-frame bungee gear. The airplane will still be available with the traditional gear, however. The spring gear adds 7 pounds to the empty weight but, as we’ll note, it yields some benefits, too.

Drag Reduction

Cub and drag go together like chicken and salad, thus most Cub drivers stoically steer the conversation away from cruise speed and toward the merits of classic yellow paint schemes. Cub Crafters tackled the drag problem by finding ways to eliminate it.

The aforementioned spring gear helped. “This spring gear is a big deal. That’s 10 or 12 miles an hour,” Lervold said. Elsewhere on the airframe, unfaired structural junctions now sport drag-reducing carbon fiber fairings. A big step was changing the Cub’s traditional cables and turnbuckles into control-tube circuitry and for the ailerons, these are hidden inside the struts, a neat engineering trick. The XCub’s cowl is substantially different than the Carbon Cub’s, primarily for engine cooling to meet Part 23 requirements. It has generous gill vents on both sides, and a reverse scoop to exit air out the bottom. The inlets are about the same size as those on the Carbon Cub. “Passing more cooling air, that slows you down, but the constant speed prop gains back some of the speed and virtually all of the surface intersections are faired,” Lervold said.

Floats will be available and that will ding the XCub’s speed. But buyers want floats available, even if they…don’t want them. “It’s important when you sell these airplanes that you have floats available. It’s a lot like a motorcycle with hard bags. You might not buy them, but you want to know that you can. Buyers want the float option, even if they don’t get it right away,” Lervold explains. The floats will be amphib Wipaire 2100As. As of press time, these aren’t approved, but Lervold says the project leads the to-do list.

Avionics, Interior

While we exaggerated about the interior being done in a Ferrari shop, the truth is not far off. We would describe the interior as luxe and not anything like you’d expect in a Cub. The seats were designed especially for the XCub and are covered in Sateen Scottish leather, with perforated inserts. The foundation is memory foam and conforms easily to the body’s nether regions.

As in the Carbon Cub, the side panels are carbon fiber but also leather upholstered. All these stitched goods add weight, but they also tamp down noise and vibration—noticeably. Cub Crafters went around the bend in providing storage pockets and cases; they’re everywhere, 10 in all, including an adjustable iPad holder for the rear-seat occupant. There are so many pockets, in fact, that you might forget where you put what. There’s even a headset locker in the rear baggage bulkhead and a clever magnetic keeper to hold the baggage door open.

Like all Cubs before it, the XCub has openable-in-flight doors and windows. But the doors are more substantial and the window latch on the left side has a multi-point latch that secures it against the slightest vibration. Vents are adjustable scoops in the overhead glass, draft-free when closed, gale force when open.

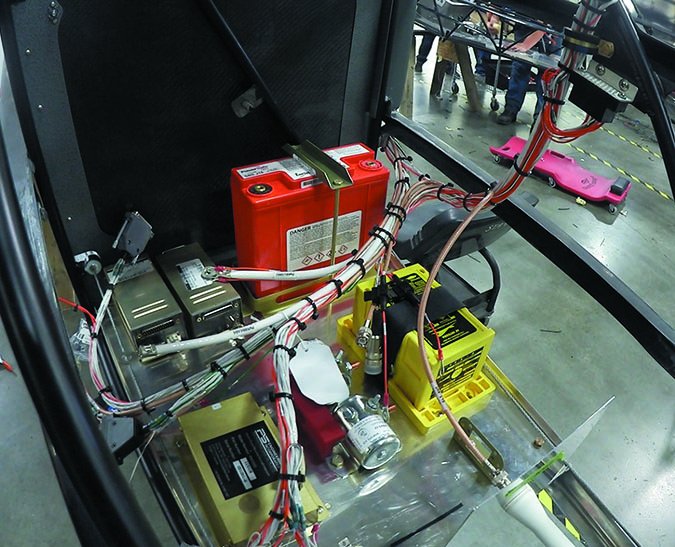

For avionics, the XCub launches into a bit of crack in the product sidewalk. It doesn’t have a glass panel, but it has the functional near-equivalent. Center panel is a Garmin aera 796, with an EI CGR-30P providing engine monitoring, power indication and engine instruments. Comm and transponder are the compact Trig TY91 and TT22, respectively, with ADS-B Out capability an option with the Garmin GDL 84. For a VFR day/night airplane, this suite is mission adequate, in our view. But Lervold said the company would prefer more choices.

“Every product has a life cycle and all the options we’ve considered are at end of life. We see what’s coming so we’re going to put something in there that’s fresh and has some life. But we’re concerned that we’re not launching with a glass panel,” Lervold explains. In other words, serious buyers will need to inquire what the short-term possibilities are for avionics if the current offerings don’t appeal. Our only complaint is that we found the data window on the Trig comm hard to read because of its low mounting.

Flying It

What’s immediately obvious in flying the XCub is that CC got the ergonomics righter than we would ever expect of a Cub. While ingress is the standard butt-first-fumble-fest-over-the-stick, the seats are impressively we’ll shaped and comfortable. One thing they’re working on: The front seat adjustment requires insertion of a loose pin that you can’t really see. That will be improved. Controls, especially the front stick, come easily to hand and the stick has a shaped grip with buttons for trim and PTT.

Lervold said the Lycoming may eventually get some form of electronic ignition—it was supposed to launch with the Electroair system—but it now has conventional magnetos, making for a conventional runup. There’s no analog tach; that’s handled by the EI engine monitor. As in the Carbon Cub, visibility over the nose during taxi is good enough not to require S-turns. Braking and turning are tight and positive.

With two aboard and about half fuel (24 gallons), our takeoff weight was about 1700 pounds, some 500 pounds below gross. With a power loading about 20 percent higher than the Carbon Cub’s, the XCub’s tail comes up a little later and the launch off the runway isn’t the same startling lurch, but the XCub wastes no time breaking the wheels loose. CC’s Whitish says the company is claiming a 170-foot takeoff roll at light weights. We saw initial climb of 1200 FPM at a at a 1600-foot denalt.

Having flown so many light sport aircraft recently, we found it refreshing to fly a proper Part 23 aircraft with well-harmonized controls and predictable control forces, especially roll. The XCub’s improved ailerons impart a near aerobatic roll rate with less observable adverse yaw than we expect from Cubs. In full-flap stalls, the XCub has a gentle and repeatable parachute mode, but it’s sensitive to bank. If the wings aren’t perfectly level at buffet onset and break, it will fall off sharply in the direction of the bank, requiring a stab of rudder to recover. Interestingly, the clean stall—47 MPH claimed—seemed to have no break, just a mild buffet and parachute mode descending at 600 FPM. Vortex generators on the wing’s top surface keep the air glued down so roll control in deep slow flight is excellent.

As with the Carbon Cub, the sight picture over the nose for level flight requires accommodation. With the nose properly pointed for level flight, the picture appears to be nose down. In trimmed level flight, we calculated a TAS of 136 MPH. Lervold said with small tires and at 24 squared, the airplane is capable of 140 MPH or about 122 knots.

Landings in the XCub are a delight for two reasons, one expected and one not. The no-surprise part was the airplane’s slow-speed envelope. Minimum energy approaches at 55 MPH feel comfortable and natural, slowing to under 50 over the fence for a three-point touchdown near the 46-MPH stall speed. (The clean stall and full-flap stall are separated by only 1 MPH.) The easy sight picture over the nose in the three-point attitude helps with runway alignment.

The surprise was how the spring- aluminum gear behaves. Unlike spring steel or bungees, it doesn’t return the bounce energy with an embarrassing sub-orbital leap, but rather a more gentle “yeah, a little fast there, I’m gonna give you a 6-inch hop.” At equivalent relative energy, an almost-decent touchdown in the Carbon Cub will be a perfect kisser in the XCub. That’s true for wheelies, too. It’s a bit of a revelation and a step forward for taildraggers. For short-field takeoffs, Lervold recommended full power and just flying off in the three-point attitude. As do most taildraggers, the XCub excels on grass, where we did most of the landings.

See the XCub in action at AVWeb.com.

Conclusion

We predict the XCub will find a good following among buyers who like taildraggers in general and Cubs specifically and who can afford a $300,000 recreational airplane. Cub Crafters hasn’t lacked for buyers of the Carbon Cub and although the XCub is more expensive, it’s a more substantial airplane.

Within the limitations of a small company’s internal capital, we think CC has done an impressive job of raising the Cub idea to its ultimate refinement. Perhaps Ultra Cub would be a better marketing grab than XCub. We’re impressed that CC has a product roadmap for more improvements.

We still have a wish list, though. First, we would like to see IFR certification. The XCub is likely to be used for sport flying and backcountry fishers and hunters, but CC has stepped the airplane up to the Bigs—bigger speed and range. This inevitably requires weather flying. Not having IFR cert probably won’t be a show stopper for many buyers, but it would still be a plus. We hope CC gets to it eventually. For the airplane intro, Lervold said it was just a bridge too far. Whether it needs a full-up glass panel is debatable, in our view, given the capability of the launch package. But buyers typically want all the bling they can get and we think the XCub will eventually have just that.

For more information, contact CubCrafters.com