There’s a certain mystique attached to tailwheel airplanes, as in only real pilots fly airplanes with the third wheel where it’s supposed to be. No modern aircraft company has exploited this more than CubCrafters, whose refinement of the sturdy Piper Super Cub has ushered in the era of the hot rod taildragger.

That’s what the company’s Carbon Cub is and what the polished and yet more powerful XCub represents. But evidently, tailwheel and high performance become mutually exclusive at the rarified edges of maximum performance landings and takeoffs and—gasp!—a nosewheel airplane just does it better.

That’s the theory behind CubCrafters slapping a nosewheel on the XCub, morphing it into a revisitation of Piper’s market-expanding Tri-Pacer, the Rodney Dangerfield of ragwing airplanes. The NXCub is currently in the final throes of certification and if CubCrafters is right, it will expand the buyer pool substantially, assuming that the $400,000 price tag isn’t over the top for a rag-and-tube two-place airplane. After flying the airplane, dyed-in-the-wool taildragger pilots will have to hitch up their britches and admit the NX will do things that the tailwheel version won’t. Where the two approach parity in runway performance, the NX allows the pilot to do the deed with less agita and, admit it, less skill and a lower likelihood of balling the thing up in a ditch.

ALL IN THE PLAN

The XCub appeared in 2016 as essentially a Part 23 certified version of the Carbon Cub, which CubCrafters had developed as a popular LSA. To meet the cert requirements, it had an additional 300 pounds of mostly structural additions and a bigger engine, the Lycoming parallel-valve O-360 rather than the ASTM Titan O-340 used in the Carbon Cub. Despite its high price, the XCub has been a modestly strong seller, although displaced recently by kit versions of the Carbon Cub, whose place in the LSA market has faded.

The XCub program was an expensive one for CubCrafters and from day one, says company founder Jim Richmond, the idea had been to offer a nosegear version of the airplane, something that hasn’t been done for a certified airplane since Piper converted the Pacer in 1951.

“We decided that we wanted an airplane we could convert to nosewheel, tailwheel, straight floats, amphibious floats and skis. So when we went through the certification process, we did all of those load cases,“ Richmond says. After the XCub was certified and in production, CubCrafters picked up with the nosegear version and has been progressing apace. But the COVID-19 pandemic has put the project about two years behind due to FAA delays. (The version I flew was a fast-build kit experimental.)

The payoff? Same as it was for Piper. “There are approximately seven pilots who are comfortable in a nosewheel airplane for every one comfortable in a tailwheel airplane. So, yeah, it’s got to affect sales on some level,” Richmond says.

If the demand is there, CubCrafters can’t yet meet it because of COVID-19-induced supply chain shortfalls. “We can’t get engines and props. We’re over a year behind on deliveries. Whether or not we could increase that, the short answer is we could. We can’t get engines and props any faster,” Richmond adds.

Thus far, sales of the X versus the NXCub have been about 50-50, but all of the NXs have been factory-assist fast builds.

TAIL VS. NOSE

Outwardly, there isn’t much difference between the tailwheel and nosegear version of the airplane. In fact, according to Brad Damm, CubCrafters’ sales and marketing VP, the airplane can be bought with a quick-change option that allows converting the airplane from nosegear to tailwheel and back again, which two people can do in a half day. The basic XCub price is $390,000, with the NX at $400,000. The floats add $70,000 and the IFR panel brings it to $430,000.

When the tailwheel airplane is converted to the nosegear—or delivered that way—the main gear is placed 16 ¾ inches aft and the wheel axle line is shifted back almost 32 inches. The main legs are spring aluminum, but the legacy A-arm gear is also still available. The gear leaf mounts outside the fuselage, not through a box structure as is typical of many airplanes. When the gear is aft, the mount slot for the tailwheel version is covered by a fairing, so the whole thing looks finished. The fairing also carries a step for getting into the airplane. You need it if the airplane has the big tundra tires.

At the tail, the wheel and control cabling come off to be replaced by a sturdy steel skid and given the way the airplane is flown—at least the way I flew it—you need it. You can really haul back on the stick for a sporty deck angle and the skid will definitely drag. At the other end of the airplane is a trusswork for the nosegear that’s just as sturdy.

It mounts on its own tubular truss structure placed as far forward as possible, just barely behind the prop arc. It has something unusual for nosewheels: trailing link suspension. This is more commonly used in retractables and is prized for its ability to smooth landing touchdowns. On the NXCub, it helps absorb the hard touchdowns you can do with this airplane routinely. More on that in a moment.

The nosewheel is full castering so you steer with brakes at slow speed when the rudder doesn’t have enough bite. It swivels through 95 degrees on each side so with the NX’s powerful Grove or Beringer brakes, sharp taxi turns match the taildragger’s radius. And you can’t put the airplane on its nose if you get greedy with the pedals.

The nosewheel has another trick. It has a removal pin that, when withdrawn, allows the wheel to pivot through 360 degrees, so you can push the airplane backward and steer it without need for a towbar, just what you’re gonna want in the outback.

There’s no free lunch on the weight. Damm said the nosewheel structure and wheel add about 40 pounds of additional weight and that biases the center of gravity slightly forward, by about two inches over the taildragger version. The example I flew had an 894-pound useful load, so it can afford the minor hit on payload. With 49 gallons of fuel aboard, that leaves 600 pounds for people and stuff. Basically, it’s a two-person outback machine with 200 pounds for gear or another hundred if you don’t have to fly far. Lemhi County airport in Idaho, for example, is 30 or 40 miles from a cluster of popular outback airports. The NXCub might as we’ll have the names of them stenciled on the cowling.

HIGH STYLE

Most outback utility airplanes are closer to Jeeps than Jaguars: rough interiors, minimal instruments and creature comforts packed in the tent bag in the back, if there are any at all. As with the XCub, the NX is just the opposite. It’s we’ll appointed with leather seats and an especially comfortable throne up front. The rear seat is a sling-type that’s removable to open up the entire area for baggage. If a solo camping trip is envisioned, you can carry 32 gallons of fuel and 500 pounds of gear. Bring the generator and cappuccino machine.

There are nice little details, like side pockets for sunglasses and maps, if you still use paper topo charts. There’s an iPad holder for the rear passenger to ward off terminal boredom as the stunning snowy peaks stream by the windows. It can, of course, Bluetooth to the avionics.

And on that count, there are two packages. One is a basic panel with a Garmin aera 796, Trig comm radio, intercom and transponder. No one will get this; they’ll all want the Garmin G3X package with integrated comm and probably the backup attitude gyro and Garmin GMC-307 autopilot. One thing lacking here is that the NX is not IFR certified, at least in the Part 23 version.

Certification is pending, but will probably be this year sometime if the FAA catches up from its COVID-19 delays. The EAB version—certainly a viable choice in the fast-build program—can be flown IFR if the owner deems it desirable. (I would.) It will need an IFR-approved navigator, such as Garmin’s GTN series.

FLYING IT

First, let me get this out the way. I never liked the looks of the Tri-Pacer and I don’t feel any different about the NXCub. The XCub from whence it comes is as stylish a taildragger as the Stinson Reliant or Spartan Executive. When a thing looks right to the eye, it just does and when you monkey with it visually, it can’t look anything but wrong. That said, a Caterpillar D-9 is no beauty queen either, but its form distills from its function.

It’s the same with the NXCub. I would have never guessed that its performance—or at least one aspect of it—would be so transformed by the addition of a nosewheel. Part of that accrues from the power provided by a custom Lycoming IO-390 at 215 HP. (See the sidebar for details on the engine.) It has 35 more horsepower than the XCub, which is itself generously powered.

With big tundra tires and that nosewheel hanging down, the NX is not a fast airplane, but it’s pretty quick for a Cub. Down low with everything forward, it will cruise at 145 MPH, but burning 14 gallons per hour. That’s not an especially economical or practical power setting, so at 65 percent power, expect more like 120 MPH at 8 to 9 gallons for a 600-mile still air range. I doubt if the airplane would be flown much on legs that long.

Still in the experimental status, the NXCub has but a sketchy POH and little useful data to draw from, especially with regard to published takeoff and landing data. Suffice to say by empirical determination, the data for both of these is … short. Really, really short. For takeoff, Brad Damm had me haul back on the stick and firewall it. There’s sufficient power there to just yank the airplane off the runway along its thrust vector and drag it into the air without trying very hard in a hundred feet or so, I’d guess.

Pitch the nose down a little and it accelerates into a brisk climb. In fact, I got quite a bit behind it because I’m used to a J-3’s anemic climb rate. I was blowing through pattern altitude before the turn to crosswind.

Landings were similarly adrenaline pumping. On the ground, Damm had sat on the tail and dropped the nose for me to demonstrate that the nosegear could take anything I could throw at it. So a perfectly acceptable landing technique is to cram the airplane down on the mains and stand on the brakes. I did this on a grass runway, so no fear of flat spotting the tires. But before I tried that, I had done slow flight and a stall series, hunting for the indicated stall. It occurred around 33 MPH indicated, with no discernible break. You can force a break with a dose of power and a high pitch rate transition.

So I should have been flying the approaches as slow as 43 MPH, but I never got it quite that low. More like 55. Even at that, dropping the nosewheel and locking the brakes produced a satisfyingly short landing. Valdez, here I come. “We were able to have competent pilots but who weren’t familiar with the Idaho backcountry … to be entirely comfortable going into some of the more challenging strips,” Damm told me. I would be, too, even at high density altitude, given the NX’s surplus power. At 8000 feet density altitude, it would still be capable of 140 HP, I’d estimate. You’d have to watch the weight, but the airplane would be quite capable in those conditions.

Some of the most successful engines in general aviation have evolved from what went before them more directly than from a clean sheet. The IO-550 evolved from the IO-520, the O-360 series was an outgrowth of Lycoming’s successful O-320. It’s looking like the IO-390 will be the next success story.

In a way, this is what we used to call a parts-bin project. Take existing components, mix and match and you’ve got something new. In the case of the IO-390, Lycoming used the base O-360 and upped the bore with cylinders from the IO-580. The engine first appeared at AirVenture in 2002 and was marketed into the Thunderbolt line of experimental engines. In the current iteration, it has roller tappets and a bottom-up tuned induction system.

Among airplane manufacturers, CubCrafters has been adventurous in developing its own engines, as it did for the CC340 ASTM engine in the Carbon Cub. The NX’s IO-390 is a Lycoming-built engine, but it’s badged as a CC-393i as a CubCrafters-exclusive engine. What makes it exclusive is CubCrafters-spec’d lighter parts including a magnesium accessory case and sump.

Jim Richmond told me engine weight is critical for a taildragger and the CC-393i weighs only 10 pounds more than the 180-HP O-360 used in the XCub. Richmond said dyno tests consistently show as much as 220 HP, although the engine is rated at 215. (The 390 is also an option in the XCub.)

In place of conventional magnetos, the CC-393i has the SureFly solid-state ignition modules. These bolt into the standard mag mount and convert ship’s power directly to high-voltage spark, with no moving parts other than the shaft to sense crank position. Heretofore, typical electronic ignition installations have used one magneto and one electronic module, but not in this engine.

The engine has two SureFly SIMs. Since these require ship’s power, there are three voltage sources: the alternator, the ship’s battery and a backup battery that will power the ignition for 30 to 45 minutes. TBO for the SureFly modules is 2400 hours. —Paul Bertorelli

CONCLUSION

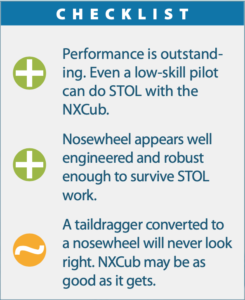

Given its semi-frumpy looks, I was prepared to hate the NXCub. And while I’ll never like the looks of it, it’s undeniably an envelope expander—both for the airplane and for the pilot. Considering the aesthetic limitations of such a change, CubCrafters’ solution is clean, unobtrusive and more functional than I would have imagined possible. The nosewheel engineering is thoughtful and elegant.

If a $400,000 two-place airplane is within the budgetary range, which would I buy, the taildragger or the nosegear? This turns out to be not such a simple decision. If I were doing the serious backcountry flying the airplane is intended for—including carrying all the gear into rough, remote strips—it’s a no-brainer to go with the NX. Not only will it perform better than the XCub, it will do so requiring less skill and with more tolerance for lack thereof.

But if I did that sort of flying only occasionally or not at all, I’d go with the taildragger version. As I said in the July 2016 report, it’s a refined, comfortable tailwheel airplane with good performance and good looks, too. Of course, if money is no object, you can have it all: Buy both the nosegear and the tailwheel conversion, floats and skis. That will push the whole deal over a half million, but the payoff would be the most flexible airplane for pure fun on the planet.