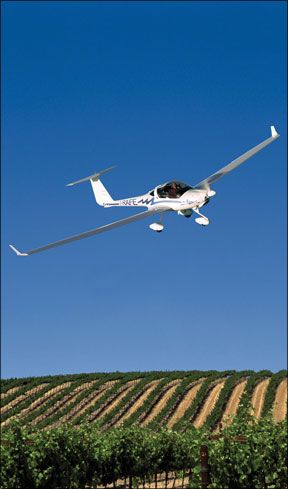

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II in Europe, Germany stunned the world by fielding the most advanced and competent air force on the planet. And it did that despite Draconian post-war treaty restrictions that all but prohibited combat aircraft development. But the pilots came from a different tradition-a passion for gliding and soaring. That continues yet today with most of the worlds glider production centered in Europe, including the re-introduced HK36 Super Dimona motorglider from Diamond Aircraft. “New” doesnt exactly apply to this airplane because it has been in and out of production for 20 years. In fact, the design is really responsible for much of the way Diamond airplanes look, feel and fly for before it was a powered airplane company, Diamonds predecessor, HOAC, was a motorglider company, with antecedents extending to 1980. Although motorgliders are a rarified taste in the U.S., Diamond is making another run at selling the HK36 to the North American market. It pitched them in the early 2000s with mixed results, but when the DA40 and DA42 projects took off, Diamond had no room in the Wiener Neustadt factory in Austria to produce them, so the project was shelved. About a year ago, Diamond restarted the line to produce a limited number of HK36s and the sales effort is being handled not directly by the factory, but by Great Lakes Aircraft Sales, a major Diamond dealer in the Chicago area. Diamond may find an emerging opportunity in “full-circle” pilots who are affluent enough to buy new airplanes but don’t want to support aircraft that require them to maintain a medical. Light sport fits that design brief and so does a motorglider, which can be flown by a pilot without a medical and even a drivers license, for that matter. (See the sidebar on page 19 for more detail.)

A Compromise

Motorgliders of all types represent a compromise of sorts and the HK36 is no different. The design motivation is that for

glider pilots, arranging an aircraft tow can be a pain if the gliderport is busy. Winch tows are more common in Europe than in the U.S., but they require a higher degree of skill and good soaring conditions to make much of the flight, since the release altitude is typically lower.

Motorgliders address this by allowing a self-launch with the engine, meaning there’s no delay waiting for a winch or towplane and you can fly some distance to find decent green air for soaring. Cross country flights are also doable, if not entirely practical due to speed and range limitations.

Of course, being a compromise, a motorglider needs to do something with the prop when and its in soaring mode. In the HK36, its simply feathered, while in one other type, the engine is actually retracted and stowed.

Model History

Its no overstatement to say that Diamond owes its lineage to the HK36. It evolved from HOAC-Austria Flugzeugwerks H36 motorglider which first flew in 1980. The follow-on model, considerably reworked, appeared in 1989 and was brought into production as the HK36 Super Dimona in 1990. The original airplane had a 90-HP Limbach L 2400 engine, but this was soon displaced by the Rotax 912, which Diamond retained when it went forward with the Katana project.

A year later, the current owners of the company acquired HOAC and eventually renamed the company Diamond Aircraft. Their first product after the HK36? The DV20, which is essentially the motorglider with the long wings sawed off, flaps added and new tricycle gear.

That model eventually morphed into the two-place DA20 Katana trainer, thence the follow-on Eclipse C-1 variant, which is powered by a Continental IO-240. If Diamond airplanes have always look like wasp-waisted sailplanes, you now know why.

When Diamond first marketed this model in the U.S., it was still available as a taildragger, but the current version-still called the HK36 Super Dimona-is available only in tricycle gear. Since the DA20 line sprang from the HK36, the two airplanes have much in common, including all-composite construction with a beefy spar, a 21-gallon fuel tank behind the cabin, a high T-tail and a wrap-around rear-hinged canopy. While the DA20 has flaps, the HK36 does not, but it does have a pair of massive manual spoilers deployed by handles on the cabin wall. This is typical of all gliders.

While the wings are similar, they arent identical. Thats because at 53.5 feet, the high-aspect wingspan is enormous and too large to fit into the typical T-hangar.

Therefore, the wings are designed to be folded for storage in a typical hangar or a glider box. The airplane is not considered towable, since the wings don’t detach in any way in the folded position. But it can tow other gliders and Diamond offers a tow package for that purpose.

One option for stowage is a dolly system that allows two people to split the wings and roll them along the side of the fuselage. The control circuitry-rods for the ailerons and cables for the rudder-remain attached, but the nav light wire has to be disconnected.

When detached, a spar carry-through splits and the wings rotate 90 degrees. In the locked position, theyre held in place by beefy leaves secured with a pair of heavy pins accessible behind the pilot seats. Working quickly, two people can do the wing trick in about a half hour, in both directions.

Rotax

In the early days of its foray into the North American market, Diamond favored the Rotax series engines-the 81-HP 912 F3. In the Katana, these delivered acceptable performance, but

owners complained about poor climb rate and overheating, which Diamond had a difficult time sorting out.

The current iteration of the HK36 has the Rotax 912 S3 at 100-HP or the turbocharged 914 F3 at 115 HP. Either way, with all that wing, the airplane doesnt lack for climb rate. Its max weight is 1694 pounds against an empty weight of 1210 pounds. That yields a power loading of 16 pounds per horsepower compared to the original Katanas 20 pounds. With the additional wing, the HK36 has climb rate to burn, even with two aboard and full fuel. The useful load is about 480 pounds so with full fuel, two 200-pounders will be over the top. If Diamond finds many buyers, we suspect most will opt for the turbocharged version. The price Delta is about $13,000 on a $177,937 base-price airplane. (Actual invoice prices, allowing for options and delivery costs, are closer to $218,000 for the non-turbo and $231,695 for the turbo.) The turbochargeds versions extra 15 HP would kick up the climb a little but would be most noticeable in a high density altitude environment where sailplanes often find themselves. The HK36 tilts toward the sailplane world so it is minimally equipped. The version we flew in Florida in April didnt even have a radio, but basic instrumentation including a digital variometer, an airspeed indicator and an altimeter, plus the engine gauges. Options range from the basic SL30 navcom to a GNS430. There’s also a high-capacity generator option for airplanes tarted up with equipment requiring more electrical demand.

As in the DA20, the cockpit is bisected by a fiberglass structural piece that serves as a console to support the throttle and prop controls. Electricals are along the base of the panel. Unlike the older DA20s, the panel is flat metal from end to end, without the breakfront design for a radio stack.

Getting into the airplane is…well, it requires practice.

You mount from the front, ahead of the wing, and grab a handhold carved into the glareshield and use that purchase to lower yourself onto the seat. To exit, reverse it. Older pilots can do this, but theyll need to apply a certain method.

Flying It

Were basically talking about a DA20 here…sort of. Ground handling is via braked main wheels and is easy enough, except for those long wings. You have to pay attention lest you clip another airplane, a fuel pump or some other obstruction. The long wings affect handling, too. Although the control inputs are on the light side, especially in pitch, those long wings impart plenty of inertia so the roll rate is on the sluggish side.

And with ailerons on the end of a giant lever arm, adverse yaw is magnified enough to make deft rudder use an absolute must. Its not necessarily easy to keep it coordinated, either. We tried some rudder coordination exercises and never did achieve that rotation-on-an-axle feeling.

Climb rate feels spectacular-we say “feels” because we had no VSI to measure it. The claimed max climb rate is 1063 FPM. Once at altitude, we tried some steep turns and stalls, all of which are Katana like, with the aforementioned exception of roll rate and the need for rudder. Like the DA20, the HK36 does a nice parachute mode when the nose is parked high after it slows to the 42-knot stall speed. No surprises there.

As a glider, the HK36 is no slouch. Its L/D max is 27, which puts it in the middle of the pack for sailplane performance. Its not a world-class competition sailplane, but its no slug, either. Shutting down the engine involves pulling it to idle and shutting off the ignition while simultaneously pulling the prop

into feather.

The engine chugs a turn or two and everything goes silent. The airplane has an optional large capacity battery so you can leave the master on with radios and instruments fully powered up. There’s an electrical sub-switch which you need to set to the soaring position to kill the electric fuel pump. Otherwise, the engine may flood and refuse to start. (This actually happened to our sister publication, avweb.com. Demo pilot Andy James demonstrated his glider prowess by landing deadstick at Plant City, Florida.)

On our flight, we had no so such problems and the engine fired up nicely three times, so we could climb back up and search for thermals on a weak lift day. Doing this-or at least staying in the thermal column-proves to be surprisingly physical work. From the ground, sailplanes look graceful and fingertip light. In the air, you have to honk the stick hard over to get a tight turn and youd better not be late with the rudder. The turn rate has to be high and the roll-in quick, so max control inputs are required.

A modern variometer aids this process immensely, but you still have to muscle the turns. Landing is equally physical. Pilots of powered aircraft are used to high sink rates, which they arrest with power. Confronted with a sailplane, the problem is just the reverse-how to judge the glide angle to get the damn thing down?

For this, the HK36 has a two-position spoiler system. The first notch locks the spoiler up and delivers about 500 FPM of drag. The second position requires a strong pull against a spring and it doesnt lock there. So that means your left hand has the spoiler engaged while your right handles the stick. That spring is strong enough that you wont want to hold full spoilers too long.

One thing we noticed is that with the long wings, its very easy to get into a PIO while trying to finesse the runway lineup. Getting behind on the rudder input will aggravate this so until you figure it out, don’t expect pretty touchdowns.

Conclusion

At perhaps $90,000 more than a typical LSA, the HK36 is definitely not a cheap toy. If we were serious about one, we would find three partners to share the purchase. Although its not LSA compliant, you don’t need a medical to fly it, so given the graying demographic of the pilot population, Diamond might find traction with this airplane.

In our view, the fun part is that unlike an LSA, in a motorglider, you can engage in the intellectually challenging pursuit of lift and if you don’t find any, well, the engine can take you home. Thats altogether not a bad way to spend an afternoon.