Altitude encoders are the doorstops of the avionics world. You have to have one, but don’t expect a sweep through the list of available hardware to yield impressive lists of features and capabilities. After all, all the gadgets do is electronically deliver altitude data to a transponder that then reports your altitude to ATC—Mode C.

Although encoders are a backwater market of sorts, the technology has inevitably been impacted by two developments in avionics: the air data computer and the slow-motion breaking wave of ADS-B. Taken together, these two developments have ignited a trend toward either using ADC boxes for transponder altitude information or incorporating the encoding function into the transponder itself. Not many new airplanes have discrete encoders these days.

This is generally good news for avionics buyers because it can eliminate the need for a separate encoder entirely and in legacy airplanes that might require a replacement, the new one can be lighter and perhaps even cheaper if it’s combined with an ADS-B installation.

What It Does

Altitude encoders were developed partially in response to ATC radar limitations. Primary radar—that is radar that skin paints airplanes and processes the returns—isn’t effective at seeing aircraft at great distances from the antenna or small aircraft at any distances. Secondary or beacon radar was developed to address this.

A separate antenna transmits an interrogation signal that your transponder sees and returns. A Mode-A interrogation requests a code—that’s the four digits you plug into the transponder—while a Mode-C query asks for altitude. And that’s where the encoder comes in. Using a pressure sensor, it converts pressure altitude data to a digital stream the transponder can interpret and pass along electronically to ATC, whose computer applies the local baro setting to accurately compute MSL altitude to the nearest 100 feet.

Not so long ago, at least for people who engage in age denial, encoding altimeters were the most common way of doing this. An ordinary looking altimeter sent a coded pulse to the transponder, which then did its thing. Encoding altimeters are still out there in the modern world, but most have been displaced by blind encoders—discrete, boring boxes that live somewhere in the maze of wiring behind your panel.

Blind encoders have proven to be relatively inexpensive and reliable, which is no surprise given how simple they are. Most use a solid-state altitude sensor with a bit of onboard logic to turn the sensor’s data into something the transponder can digest. Some museum-piece airplanes may still sport aneroid sensors, but there can’t be many left.

Historically, encoders disgorge something called Gray or Gillham code, a binary numeric code that, while simple, requires a lot of wiring to move from the encoder to the transponder. While Gray-code-only encoders are still on the market, the world is transitioning rapidly to serial data through an RS 232 link. Serial data can be coded to suit the input requirements of any avionics and it requires just a twisted pair of wires, greatly reducing installation complexity and increasing reliability.

Everyone we spoke to in the encoder manufacturing business—and that’s not many—agrees that Gray code is on the way out. Not all modern avionics accept it and the profusion of ADS-B boxes on the market all require altitude input data and may not be Gray code friendly.

“Gray code doesn’t make sense anymore. That was the technology way back when. It’s a binary format. It takes five wires just to get you to 10,000 feet,” says Sandia Aerospace’s Dennis Schmidt. Sandia still offers an encoder with dual Gray code and serial output, but Schmidt says the Gray code demand is a replacement market that will shrivel after the 2020 ADS-B deadline. Meanwhile, the hot development in encoders—if anything in such esoteric hardware can be considered hot—is miniaturization for traditional blind encoders and/or using the altitude sensing capability in air data computers and skipping the encoder entirely. There’s also strong price competition in what is already one of the cheapest appliances you can install in your airplane.

Cheaper, Not Smaller

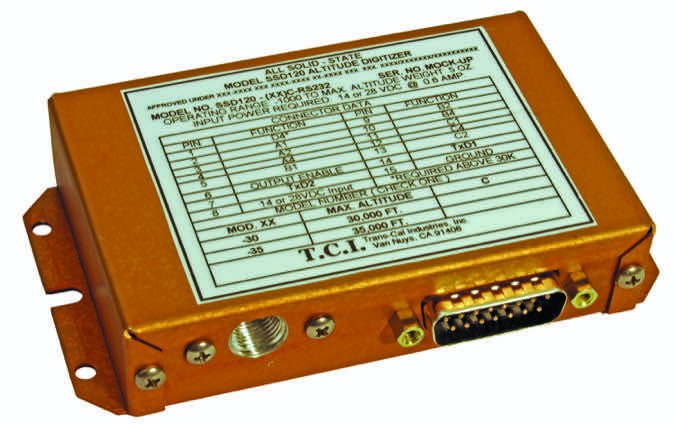

California-based Trans-Cal is the acknowledged traditional leader in altitude encoders and has a well-established record for top-of-the-line equipment. In 2007, after owner John Ferrero took over the company from his father, Trans-Cal miniaturized the company’s products in the SSD120 Nano series, which are still offered today. These aren’t quite the size of a quarter, but at 2.5 by 3.4 by 1.4 inches, they’re not much larger either.

Trans-Cal has the most complete line of encoders, offering eight models, most of which output both Gray code and serial data and include variations on connector type and temperature and operating environments, including a model designed to operate as high as 100,000 feet. The most popular option is probably the SSD120-30N, which retails for about $350. Trans-Cal encoders live inside a solid metal case and have warranties up to 42 months. Trans-Cal’s Ferrero says failures of any kind with these encoders are rare, as little as half of one percent.

Improbably, even for obscure hardware costing $350, the encoder market has become intensely price competitive, so as we go to press this month, Trans-Cal is introducing a new product called the Charlie series. Ferrero is blunt about the purpose of the new product.

“We live in sort of a Wal-Mart world. People want to buy often and they don’t care if it lasts. They just want it cheap,” he says. So the new Charlie series encoder is simply built cheaper, with a stamped aluminum case instead of an extruded, machined case and a single 15-pin connector rather than two connectors. And although it contains the same electronics as the Nano line, it’s slightly larger.

“This C-unit is designed to be an affordable solution for anybody who’s looking for ADS-B compliance, putting in a serial-data-capable unit with 10-foot resolution,” Ferrero says. He declined to say what the retail price will be, but said it will be $50 or $60 cheaper than the Nano. We take that to be just under the $300 mark. The product should be available by mid-summer 2017.

Cheaper and Smaller

Meanwhile, in its GAE 12, Garmin has pursued encoding technology that’s both smaller and cheaper but might best be called a non-encoder. The GAE 12, as shown in the photo on the previous page, is literally the size of a quarter. Its static fitting is as big the device itself. That’s because the GAE 12 isn’t really an encoder, but a smart pressure sensor.

Garmin’s idea was to offer a small, solid-state pressure sensor that outputs data into a serial peripheral bus, the same protocol computer processors use to talk to hardware. That’s piped into the transponder itself, which then does the electronic massaging to convert the data into pressure altitude for transmission to ATC.

The $249 GAE 12 screws to the back of the transponder tray and the static line connects directly to it. The advantage is that if the transponder has to be removed for repair or replacement, the GAE 12 stays put and the static system remains undisturbed. That avoids the hassle and expense of recertifying the static system for a minor repair.

The GAE 12 can best be thought of as an offshoot of air data computing; it’s simply the altitude-sensing portion of an ADC box. It works only with Garmin’s GTX 335/345 ADS-B Out transponders. Those transponders, which have become the go-to products for ADS-B compliance, can also accept Gray code and serial input from other encoders.

The GAE 12 has another trick: It serves as a configuration module for the transponder. At installation, the technician can use a computer to set up the somewhat involved parameters required for ADS-B Out transponders. Once that’s done, if the transponder is repaired or replaced, it will be automatically reconfigured when the box is inserted back into the tray. Garmin uses configuration modules for many of its products, some of which are just flash memory chips located in the harnesses. The GAE 12 is just another way of skinning the same cat.

| Product* | Typical Retail | Output | Comments |

| ACK A-30.5 | $227.95 | Gray code only. | Basic encoder suitable for legacy installations that require Gray code. |

| ACK A-30.9 | $232.95 | Gray and serial in 10-ft resolution to 42,000 ft. | Package includes harness, mounting and static plumbing fittings. Least expensive serial model. |

| GARMIN GAE 12 | $249 | SPI direct to transponder only. | Works only with GTX 335/345. Transponder does the encoding. Serves as configuration module. |

| GARMIN GAE 43 | $279 | Gray and serial in 10-ft resolution. | Garmin-branded Sandia SAE 5-35. Price recently reduced. |

| SANDIA SAE 5-35 | $450 | Gray and serial in 10-ft resolution. | Features in flight monitoring to alert pilot to altitude deviations. |

| SHADIN 8800-T | $1323 | Gray and serial in 10-ft resolution. | Old-school box designed for use with Shadin’s altitude management system. Not a player for replacement market. |

| TRANS-CAL SSD-120 SERIES | $319 to $439 | Wide variation in output formats. 10-ft resolution available. | Trans-Cal’s line is the most flexible in the industry. These will remain available even as the cheaper C-model arrives. |

| TRANS-CAL SSD(XX)C | $280** | Gray and serial output in 10-ft resolution. | The C-series is Trans-Cal’s new lower-price line. Expected to be available by summer 2017. |

* Table represents a top-level survey of altitude encoders. Not all are listed. ** Our estimate of price based on Trans-Cal information. Final prices weren’t available at press time. | |||

Market Trends

The companies we spoke to for this article aren’t of a single opinion on whether the onset of ADS-B has upended the encoder market. Trans-Cal’s Ferrero believes it has and that the encoder market has become price and volume driven. Once the market leader, Trans-Cal has lost share to other manufacturers and since encoders do basically the same thing, price is the main competition variable. “I want back some of what we lost,” Ferrero says.

But even as the market gets more competitive on price, it’s not likely to evolve much in basic capability or feature sets, which is another way of saying what you see now is pretty much what you’re going to get for the foreseeable future. Both Sandia’s Schmidt and ACK Technologies’ Mike Akatiff told us that advances in hardware miniaturization make it possible to build encoders that are smaller, cheaper and use less power than current technology. That’s essentially what Garmin did in incorporating the encoding capability right on the transponder board.

But for gadgets costing $300 or less, the margins and market aren’t there to invest in rethinking the basic discrete altitude encoder. Trans-Cal’s Ferrero says the additional testing to certify a new generation of encoders would cost at least $250,000, an investment unlikely to be returned in greater sales or margin.

“We could shrink this thing down to the size of a postage stamp if we really wanted to. But we don’t have plans to do that. The TSO certification is so onerous, we just don’t want to change it,” says ACK’s Akatiff.

As ADS-B installations accelerate—and they appear to be doing just that—the manufacturers expect demand for encoders to increase, especially for aircraft that have either older electromechanical encoders or units that output Gray code only. All ADS-B boxes require encoded altitude from some source and may or may not accept both Gray code or serial input. Then there’s the question of resolution. Most of the new encoders will output resolution down to 10-foot increments, if not down to 1-foot. Is there any need for this?

“I can’t answer that,” says Garmin’s Bill Stone. ATC’s resolution requirement is the same 100 feet it has always been and Stone says the resolution of serializers exceeds the accuracy, so what’s the point of 10-foot increments? “I don’t think it’s entirely necessary, but it’s so easy to do. If you have a way to read the data, and most GPSs do, you can read it,” says Mike Atakiff.

Bottom line: Altitude resolution shouldn’t be a buying factor for a new encoder. As Ferrero observes, it’s a price-driven market, so buying solely on price strikes us as a rational decision. We like Garmin’s idea of splitting the sensor and the encoding function to preserve static system integrity. On the other hand, new encoders are so reliable that tearing into the static system to fix one between 24-month certifications will likely be the least of an owner’s worries.