As we attempt to keep our legacy aircraft flying longer and more efficiently, more pilots look to the avionics upgrade path as a means of improving utility and safety. And while the glass-panel primary flight display and multifunction display have both earned their fair share of attention, its also correct to suggest that the combined engine monitor-shorthand for a screen that includes powerplant and airframe system monitoring-is on many owners radar. Who isn’t eager to get rid of those wiggly needles, anyway? J.P. Instruments has been a household name in add-on engine monitors, making popular the bar-graph style of EGT and CHT monitoring. Many pilots are familiar with the firms 2.25-inch gauges and while some of them can include monitoring of other engine parameters besides EGT and CHT, the limited display size reduces the number of items you can watch at once. On another end of the market are those big-screen engine monitoring systems, such as JPIs own EDM-930 and EDM-960-both roughly radio-stack width and around 5 inches tall.

RIGHT SIZE

But what if youre upgrading a panel and don’t have that kind of open real estate? It makes sense to have an instrument in between those sizes, preferably one that fits into a 3.125-inch instrument hole-heck, you have a few of those to spare, right? Well, now there is: The EDM-730/830 monitors are designed to slide right into a large instrument hole.

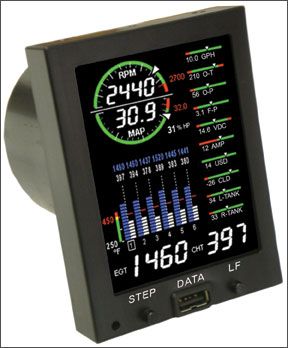

Sure, thats a great idea, but you havent seen everything yet. The front of the instrument is rectangular-approximately 4.2 inches tall and 3.2 wide-with a 2-inch-deep stub on the back that fits into the instrument hole, similar to the way the Aspen Avionics EFIS takes two vertically stacked instrument holes.

Better yet, the stub is not centered on the instrument, meaning that the edge distance is different for each surface; in turn, this means that you can install the instrument with any of the four sides facing up, and the offset provides more opportunities to clear existing instruments or panel structure. To make that work, the screen can be configured, actually on the fly, to show the data in any of the four orientations.

So, whats it packing? It starts with all-cylinder CHT and EGT monitoring-either the 730 or the 830 can be configured for 4, 6, 7, 8 or 9-cylinder engines. Whats more, the instrument is self-configuring. Plug in a new probe, and at power-up the instrument recognizes it and includes it in the scan.

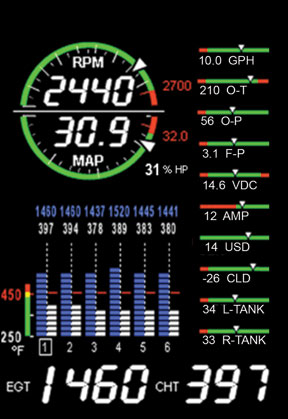

The primary difference between the EDM-730 and 830 is the inclusion of manifold pressure and RPM sensors. With them, the 830 can also calculate percent of horsepower as long as there’s also an outside-air temp probe connected. More on that later.

SECONDARY INSTRUMENTS

The EDM can be tailored in terms of the layout and makeup of the secondary instruments. You can choose where any of the horizontal bar-graph displays reside on the 4-inch-diagonal TFT display, and set their upper and lower alarm limits.

The items the 730/830 can watch include oil pressure and temperature, fuel pressure and flow, turbine-inlet temp, carb temp, compressor-discharge temp and inlet-air temp. With a fuel-flow transducer, the instrument also performs the full collection of fuel-management functions, including real-time flow rate, time to empty, fuel remaining and fuel required to waypoint (with an external GPS feeding an RS-232 data stream).

More about the display. JPI has taken extra care to make the presentation clear and professional. If you have a four-cylinder installation, for example, you wont have to look at missing bars or blank spots on the display. Every item on the display is rendered to use all of the screens area. A six-cylinder version simply has the EGT/CHT bars packed more closely together. Also, the display is modified when you have a 730 versus the 830-the layout reorients to place useful data where the MP and RPM displays would be. In the vertical (portrait) layout, MP and RPM form the upper and lower halves of a circle, but when in the horizontal (landscape) mode, they split into two semicircles side by side, with large numeric displays below them.

A large single-line display just below the EGT/CHT bar-graph magnifies the values of other indications-you can scroll through the displays choices with the STEP button. If you have ever used a conventional JPI engine monitor, the 730s methodology will be immediately familiar.

Also on the front panel is the LF button, for Lean Find. In default mode, when you press LF once, the term ROP will appear, which means its entering the Lean Find mode, expecting you to run the engine rich of peak EGT. (If you press and hold both buttons, you can select LOP for lean-of-peak operations; you can make this your default setting if you prefer.)

In Lean Find, the monitor watches the EGTs rise and notes the first and last to peak. Once it has found peak, the bottom display line changes to show the current fuel flow and the temperature delta from peak of the controlling cylinder, all as an aid to leaning. In the LOP mode, the EGT bars form an “icicle” layout, descending from the top line, to show how far each cylinder is lean of peak EGT.

The EDM-830, as mentioned, also features an engine-power calculator, and here its done correctly: Rich of peak it uses mass airflow (manifold pressure x RPM, roughly), but lean of peak it uses fuel flow to calculate power. This attention to detail means that the calculation can be remarkably accurate without having to create intricate engine lookup maps.

How does it work? We had a chance to fly with Lance Turk, designer of the first all-in-one engine monitor, the Vision Microsystems VM-1000. He is currently flying the experimental version of this instrument, called the EDM-740, in his Glasair I.

EASY ON THE EYES

Even cross-cockpit (Turk has the unit mounted in the small left subpanel) the 740s display is clear and legible right down to the smallest menu item. And while the individual bar-graph

gauges do look alike, the ability to place them in any order allows each pilot to stack them in order of importance. You can also choose to leave a field blank, in effect creating a more prominent grouping for, say, oil pressure and fuel flow. In flight, fast-responding probes are worthy of mention-during the several engine-leaning cycles we tried, the EGTs immediately followed movement of the mixture control, and the Lean Find function looked stable and easily digestible to a pilot who is busy doing other things (like flying). And while we didnt have the chance to validate the percent-of-power readings, they definitely passed the sniff test based on our understanding of the Lycoming O-320.

And those who want to track engine health will be excited to learn that the 740 includes integral data logging-it can absorb data at 6-second intervals for some 200 hours. Access to the data comes from a front-panel USB port. Plug in your USB stick, press a few buttons, and the stored data goes rushing out. We watched a download, and can say that the new USB hardware is dramatically faster than the serial-based transfer on the older EDMs.

Installation should not be back-breaking, especially if you already have a JPI engine monitor. The harnesses are exactly the same, as are the probes. In theory, this could be a plug-and-play with a later-model EDM-700 or 800. At the moment, the EDM-730/830 are approved as primary replacements for CHT, oil temp and TIT, meaning that those stock instruments can be removed.

Prices are competitive. A basic EDM-730-4 (four-cylinder) is $1995, and $2750 for the six-cylinder version. Step up to the EDM-830, which includes the MP/RPM sensors, fuel flow, oil temperature and pressure probes, for $3795; its $4295 for the six.

Thats approximately $500 more than the old price of the EDM-700/800 series. J.P. Instruments has, in our view, greatly expanded the capabilities of the small-format engine monitor in the EDM-730 and 830, packing a lot of capability into a clever, compact package.

Marc Cook is editor of Aviation Consumers sister publication, KITPLANES.