Its not much

slammed against a hardened steel seat 10 times a second swirled in a gale of white hot combustion gas. When an engine tanks prematurely or needs a midstream top overhaul, its often something to do with exhaust valves-bad guides, leaky seats, cracks around plug bosses originating near the exhaust valve.The engine makers and airframers have tried to meet these problems head on with mixed success. Cylinder cracking and valve issues continue to trouble owners, seemingly in cycles.

But with little fanfare and without even intending to, Cirrus Design may have just launched the boldest exhaust-valve rescue mission yet by all but mandating lean-of-peak operation for its new turbonormalized SR22. Its not the first time an airplane company has put lean of peak in the POH, but how Cirrus got there is one of the more interesting recent developments in GA-equal parts of good engineering, grass roots proselytizing and shrewd management.

Whats more interesting is this: Cirrus uses a variant of the IO-550 that both Mooney and Columbia have in their new turbocharged models, the Acclaim and the Columbia 400, respectively. Yet each airplanes POH calls for a different leaning strategy and the differences between the three arent subtle. What may be shaping up here is a laboratory of sorts shedding light on-if not proving-whether lean-of-peak operation has all the benefits its proponents claim for it. (Fuel savings are a given, in our view.)

And in the background is the question of where Cirrus might go with this. Its decision to award its turbocharging business not to its prime engine manufacturer, Continental, but to an outside vendor, Tornado Alley Turbo, is significant. It goes against the grain of most OEMs rolling along with either Continental or Lycoming simply due to inertia-its just more convenient and politically correct, even if a little mediocre engineering gets swept under the rug as a result. Its not hard to imagine how Cirrus might leverage this into other big projects outside the normal realm of engine development. The Cirrus SR22 TN is not just a fast airplane, it could be a big deal in the future of light aircraft powerplant development.

How This Happened

Consider some numbers: In 2006, Cirrus sold 760 airplanes, a 20 percent increase over 2005. If it continues that trend, it will sell more than 900 airplanes in 2007, but even if sales level off, Cirrus will sell about 600 SR22s. If past sales patterns persist, the markets taste for turbocharging means that about 450 of those airplanes will be turbocharged. And those turbo systems will be built not by Continental nor Cirrus under a new or amended type certificate, but by Tornado Alley Turbo, under an STC arrangement. To put that in perspective, Cirrus has about $240 million in business riding on a modest little mod and research shop in Ada, Oklahoma. Airframe manufacturers have dabbled in STC deals with outside vendors in the past, but we cant remember anything quite this bold. Why? Like the engine companies, airframers have traditionally held their own engineering prowess in high regard while looking askance at STC houses as mere pretenders. For reasons related to pride and sheer industrial inertia, established airframers just havent been good at picking diamonds from the rough of outside technical talent. STC arrangements are sometimes seen-rightly or wrongly-as not as safe as type certificate solutions because testing may not be as rigorous.

The traditional way of marrying a turbocharger to an engine is for the airframer to spec the requirements and have the engine maker perform test stand work and provide engineering advice. But the installation has been up to the airframer. Sometimes theyve gotten it mostly right and sometimes theyve gotten it wrong.

Turbocharger installations have been botched enough to give many owners an inaccurately skewed view of ownership costs, not to mention worries about operating issues like detonation. Thats one reason, perhaps, why market interest in turbocharged models has waxed and waned. Cirrus was late to the turbocharged bandwagon because of these very fears.

“We flew our own turbocharged installation here four years ago or so,” Dale Klapmeier told us, “and we were getting very good performance. We saw a lot of benefits in turbocharging the SR22. We did not pursue it at the time because of the uncertainty in 100-octane fuel.” Klapmeier says Cirrus didnt want to sell buyers an airplane that would be obsoleted by lack of high octane fuel. Further, he said, its in-house turbo version had cooling issues that Cirrus wasnt sure how to correct.

Looking Outside

So Cirrus dropped the turbo project and took a different path. It bought the entire

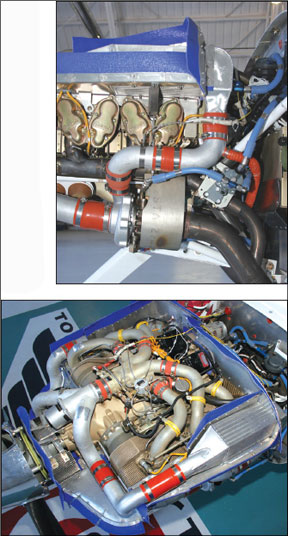

pre-engineered turbo system lock, stock and mixture knob from Tornado Alley Turbo, which launched the turbonormalizing of the SR22 on its own, based on pressure from Cirrus owners who wanted to go faster. Tornado Alley planned to add the SR22 turbo option to its Bonanza, Cessna and Cardinal aftermarket kits.

Cirrus move was a shrewd business decision, in our view. Rather than saddle its own technical staff with the Everest-steep learning curve of sorting out a turbo design, it realized that Tornado Alley had already done that.

“George (Braly) came up to Duluth with the turbocharged G1 last winter and we flew with him. I was blown away with the performance and ease of operation and the simplicity. I was blown away with the weight, too. Its a light installation,” Klapmeier says. Hes upfront about the Tornado Alley approach just being a better design, having solved serious cylinder temperature problems Cirrus encountered on its own.

Given Tornado Alleys success and technical acumen, Cirrus probably got a better system than they could have designed on their own. Less obviously, they also got a paradigm shift in engine operating philosophy that is, in our view, significant.

The Matter is Settled

Perusing our archives, we can produce an article or two in which we describe in tedious-occasionally anguished-detail the then ongoing debate about the merits of lean-of-peak engine operation. This would have been circa 1997-a full decade ago. The debate was ignited by General Aviation Modifications-the progenitor of Tornado Alley Turbo and Advanced Pilot Seminars-when it developed GAMIjector calibrated fuel nozzles, which nicely smoothed out the air/fuel imbalances in Continental and Lycoming engines. With balanced fuel distribution, GAMI discovered that many contemporary engines would happily run lean of peak EGT, saving fuel and at much lower CHTs. In truth, GAMI

re-discovered lean of peak, since the method was widely practiced in the heyday of high-horsepower radial engines during the late 1940s.

None of this sat we’ll with Lycoming, Continental or some of the major engine shops. To them, it wasnt quite apostasy, nor could it be because any intelligent person who studied the graphed data would instantly grasp the physics. And Continental had itself worked with Piper to establish lean-of-peak operation for the TSIO-520-BE in the 1984 Malibu and it approved similar operation in other engines.

But if GAMI was red hot on lean of peak, TCM was cool and Lycoming was all but hostile. In 2001, it published what became known as the “experts are everywhere” bulletin, with the “experts” taken to be GAMIs George Braly and associates. Lycoming said the “experts” were pushing lean of peak, but it was a bad thing.

It acknowledged the theory of lean of peak, but argued against it because typical aircraft instrumentation didnt allow it to be done correctly. Lycomings argument wasnt entirely without merit, but it utterly ignored the sophistication of multi-probe digital engine monitors and the underlying supposition was that pilots lacked the skill to understand and manage lean-of-peak operation.

What Lycoming hadnt counted on-nor Continental, for that matter-was how much more sophisticated, curious and motivated aircraft owners had become about engine operation thanks to the Internet and advanced training. Pilots are simply less willing to buy the same old unfounded boilerplate arguments from the engine manufacturers.

That curiosity, fueled by Bralys research work at GAMI, led to the launch of Advanced Pilot Seminars, which offered expensive, weekend advanced engine theory and operation courses. These were we’ll received and, more important, we’ll attended. Moreover, Braly and his APS associates John Deakin and Walter Atkinson occasionally took their engine show on the road, including to the annual Cirrus Migration held in Duluth, Minnesota.

The aviation press has nearly granted sainthood to Braly and company for the same reason the APS seminars proved so popular: GAMI/TAT/APS has proven accessible and always forthcoming with whatever detailed information owners or editors wanted about engine operation, which plays we’ll against the insularity of Lycoming and Continental.Moreover, visitors and APS students could see this with their own

eyes in GAMI/TATs advanced test cell and take away notebooks full of eye-glazing graphs and data. Taken together, these developments stirred an ongoing buzz among owners, pilots and potential aircraft buyers, especially Cirrus customers, more than one of whom put a bug in the Klapmeiers ears about GAMI/TATs work. But Dale Klapmeier told us that flying the TAT SR22 made offering it as an STC a no-brainer.

And its no mistake that splashy color ads for the Cirrus TN aircraft prominently feature mention of the association with Tornado Alley. The Klapmeiers understand the grass roots cachet TAT enjoys with buyers.

What It All Means

Although Cirrus holds its developmental cards close to its chest, everyone in the industry understands that the next big thing in the glacial advancement of aircraft engines will be electronic controls of some kind, specifically FADEC. To its credit, Continental read these tea leaves ahead of anyone else and bought a company called Aerosance, a startup launched by a group of former Hamilton Standard engineers. Their work evolved into what has become Continentals PowerLink FADEC. But after more than seven years, Continentals FADEC has yet to find wide market acceptance. Only one OEM-Liberty Aerospace-is offering it on new aircraft.

Cirrus has tested the Continental FADEC system and Klapmeier believes electronic controls of some kind are inevitable. “Cirrus is not offering it yet because I don’t think its quite ready,” Dale Klapmeier says, this despite nearly a decade of development work. Klapmeier says there has been virtually no customer demand for FADEC and that Cirrus sees the system as pricey, heavy and without known benefits for buyers. “It is coming. I think its a good idea, but Im still a little concerned…is the market ready to pay the price in both cost and weight?”

GAMI/TAT has its own developmental FADEC called the PRISM system, which has been validated in the test cell but not in the air. In our view, PRISMs development has suffered for lack a capital inflow and the over-the-top push that a committed major aircraft maker like Cirrus might give it. Does that mean that Cirrus might be the missing benefactor for PRISM?

“Watching how long it takes to develop an engine,” says Klapmeier, “and the changes that even a company like Continental brings are pretty slow and methodical. I don’t see the PRISM coming quickly, so I havent paid a whole lot of attention.” Of course, the same could be said of TATs Cirrus turbo system. Klapmeier concedes he was skeptical until he flew the TAT turbo.

Because its an ignition-only system, PRISM is lighter and simpler than Continentals FADEC, but its developmental evolution isn’t as advanced. Now that TAT has a foot in the door if not quite a seat on the board at Cirrus, this could change in a hurry.

TATs George Braly says the Cirrus relationship has and will open doors. “It gives us the opportunity to put this product out there and say to somebody like Cirrus that we would like to see this system on our turbo system and heres why it enhances the system. It gives us a ready built-in market for it and an enormous amount of initial credibility.” To sustain that credibility, TAT will need to stay on track with Cirrus by delivering and perhaps improving its turbo system. Further, it will have to address any kind of quality or technical shortfalls that could surface in the TAT turbo.And it will need to get busy with PRISM. Very busy.

Braly and TATs Tim Roehl have been canny about mining modest opportunities with other companies and the deal with Cirrus is anything but modest. (TAT has doubled its workforce since last summer to keep abreast of Cirrus rocketing demand for turbonormalized SR22s.) Is it conceivable that a clean sheet engine-designed from the ground up to run lean with fully electronic controls-could evolve from TATs relationship with Cirrus and other companies?

“Weve got a notion of how to do that effectively,” says Braly. “Its a big effort.” Although Cirrus has its hands full with current developmental work, especially its emerging jet, it wouldnt surprise us if it IPOd in the not-too-distant future. Investors may like the fact that within two to three years, Cirrus will have built 5000 aircraft, a captive market that may make its jet immediately viable. Cirrus has proven it can build airplanes in volume.

Its also not outlandish to think Cirrus and/or a consortium of investors might make Teledyne an offer it cant refuse for the Continental Motors operation. Such a development would fundamentally change the aircraft piston-engine landscape.

But the reality is that with the TAT STC deal, Cirrus has already done that. In 2007, more than half of all the single-engine high-performance aircraft sold will be turbonormalized by Tornado Alley, a company that just a few years ago was the subject of dismissive service bulletins from Lycoming ridiculing the idea of lean-run engines.

None of this means Lycoming or Continental might as we’ll fold their tents. But we think both companies will have to rethink how they do their engineering and development, especially Lycoming. Its still digging out of a quality control debacle, it has no visible electronic controls and, worse, its own sister company, Cessna, may turn to Continental for power for its new Next Generation aircraft. “Id be willing to bet all I own that the new Cessna will have a Continental engine,” one industry source in a position to know recently told us.

Weve been told that Lycoming has explored initiatives with Toyota, possibly on engine development. Thus far, nothing public has come of it. GAMI/TAT, and now Cirrus, have just been better at understanding what customers want and talking about it openly enough to enjoy overwhelmingly favorable buzz in the market. And that, more than anything, explains why Cirrus ads confidently tout Tornado Alley Turbo and not Continental.