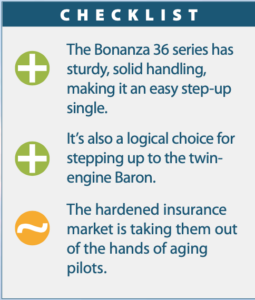

First, the good news. Since the earliest 36-series Bonanza entered the market in 1968 (and is still in limited production today as the G36), there are a variety of used models at multiple price points to choose from. The bad news for buyers in the current market is that prices are up—way up—for all models. Bonanza sales pros tell us prices for the Model 36 are inflated over 30 percent from where they were just a short time ago. Worse is that demand is zapping the inventory of good airplanes, with many selling before there’s a chance for retailers to advertise them.

But it’s long been a fact that the flagship Bonanza, with its roomy cabin, crisp and predictable handling and good fit and finish, ranks high in owner satisfaction. Here’s a look at the current market.

LONG HISTORY

The model line started long before the Bonanza 36 came on the scene in the late 1960s. The Bonanza airframe has been in continuous production since 1947, when the first V-tail was built—an astounding fact in itself. The 35 Bonanza was the first high-performance postwar single and was markedly different from the average light airplane of the day. Base price of the first models was $7975 ($99,400 in 2021 dollars).

Textron recently announced that a 75th anniversary version of the Bonanza G36 will be available in 2022, marking 75 years since the original Model 35 Bonanza was sold. With more than 18,000 built, the Bonanza is said to be the longest continuously produced aircraft in history.

By 1967, Beech had a gaping hole in its model lineup. Archrival Cessna had been selling its six-place retractable single, the 210, since 1960 and by the end of the 1967 model year had rolled 936 through the factory doors. Cessna also had the 206 for the utility market.

Beech didn’t have a truly comparable airplane. The V-tail, S35 Bonanza, introduced in 1964, received a 19-inch cabin stretch that permitted the installation of a fifth and sixth seat. These were called “family” seats, and they really weren’t suitable for adults. The company kept working on a true six-place airplane.

For the 1968 model year, Beech introduced a stretched version of the Bonanza, with six seats, a conventional tail like that on the eight-year-old Debonair (redubbed 33 Bonanza that same year) and an aft set of doors.

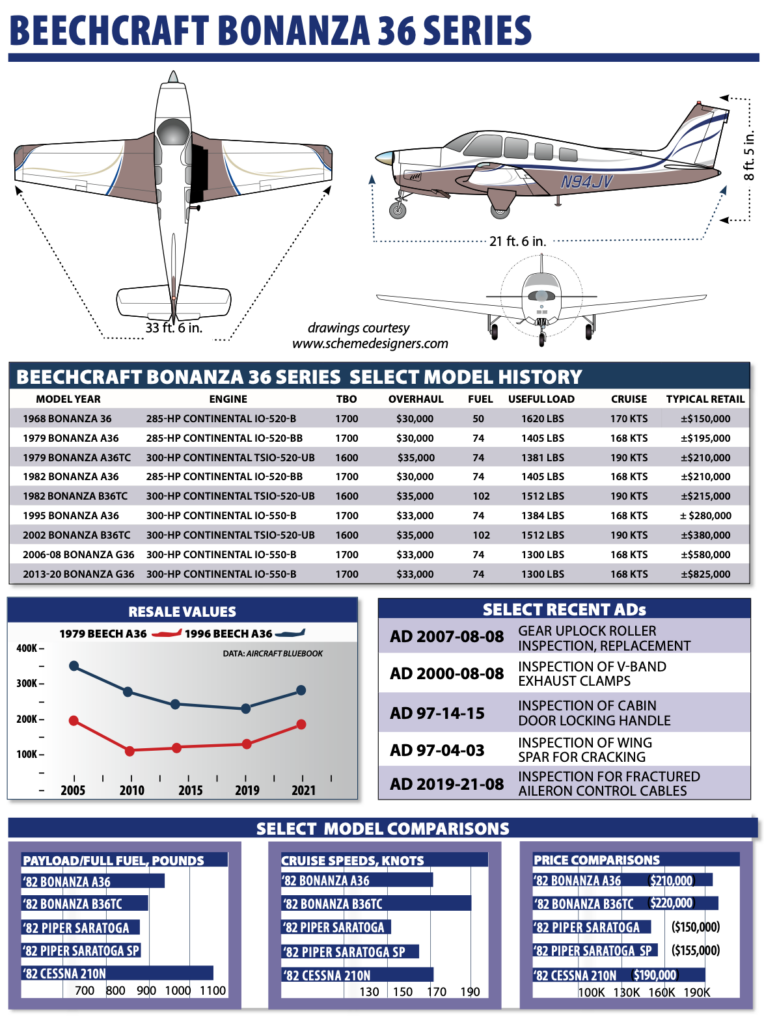

The price of this first 36 Bonanza was $40,650, which rose to an average of $47,050 equipped. That same airplane is now worth an average of $150,000, according to Aircraft Bluebook.

The original 36 was equipped with a six-cylinder Continental IO-520-B engine producing 285 HP and swinging a two-blade prop. It had some limitations compared to the later models: Club seating was not yet available and the standard fuel capacity was only 50 gallons, with 80 optional.

The stretch was accomplished by adding 10 inches to the fuselage of a 33 Bonanza; the 36 was not an all-new airplane. The length was added in such a way that the cabin moved forward, relative to the wing. Empty weight rose only 31 pounds.

The 36 was aimed at the utility and charter market dominated by Cessna, as a good choice for air taxi and cargo hauling. This was in contrast to the V-tail Bonanza, which was sold as an upscale business airplane. The 36 Bonanza could even be flown with the rear doors removed. Of course, the original 36 could be outfitted with options like a more plush interior. In 1970, the A36 debuted with the popular club seating option. The marketing focus changed, positioning the A36 more as a larger version of the other Bonanzas rather than as a utility airplane. Many of the “luxury” options became standard equipment.

In 1973, the fuel system was changed. Standard capacity actually went down to only 44 gallons, with a 74-gallon extended range system available. We believe it’s highly unlikely that there are any standard-capacity A36s in the fleet. An 80-gallon system was made standard in 1980.

As the years passed, the basic A36 remained largely unchanged, though in keeping with its real-world mission—a personal user’s IFR platform—more and more equipment was made standard. By 1976, an autopilot was standard, along with what is now a basic IFR suite.

There has always been a need for turbocharging, so Beech introduced the A36TC in 1979. With a 300-HP Continental TSIO-520-UB, equipped with a variable absolute pressure controller that automatically maintained manifold pressure during altitude and temperature changes, the airplane showed a lot of potential. Only 272 were sold in three years, as pilots complained about having only 74 gallons of fuel aboard when the engine wasn’t exactly fuel efficient. Today, aftermarket extended-range fuel tanks solve the issue.

In 1982 Beech released the B36TC, which used the Baron 58 wing. It was longer (for better performance at altitude) and carried 102 gallons of fuel. The changes punched up range by a whopping 50 percent.

The biggest change to the normally aspirated airplane came in 1984, when a 300-HP Continental IO-550 replaced the IO-520. There was an all-new (and very we’ll laid out) instrument panel. Gone was the trademark Bonanza “throwover” control wheel with its massive central column in favor of a pair of ordinary control yokes. It also had the round vertical-placed engine gauges to the left of the radio stack. With the introduction of this airplane, the base price had roughly quadrupled over the original 36: $160,700 ($429,896 in 2021 dollars) with a current average value of $225,000.

The bigger engine can be retrofitted to older aircraft—a popular mod, judging by our reader feedback. TBO on all of the engines that have gone into the “straight” (non-turbo) 36 Bonanzas is 1700 hours, with the estimated overhaul cost on the 520 currently at $30,000 or so and $33,000 for the 550. An owner opting to switch rather than overhaul not only gets the extra power (for not a lot more fuel burn), but better service reliability as well.

The current G36 (G for Garmin 1000 glass panel) Bonanzas are the only Beech singles still in production; the last F33As were built in 1994.

INFLIGHT MANNERS AND AUTOPILOTS

Bonanza owners have bragging rights to planes that are simply pleasant to fly. For hauling passengers loaded in the spacious cabin, the 36-series Bonanza is comfy on long trips, and this is why pilots love Bonanzas. The handling for its intended mission is just about as good as it gets, although the 36 is regarded as more ponderous than the sports-car-like V-tail 35. This is due mostly to the stretched fuselage, although that has its advantages over the 35 when it comes to weight and balance, and of course convenient loading.

One characteristic of the classic V-tail that is blessedly reduced in the 36 models is the notorious tendency to Dutch roll in turbulence. The extra length makes for a more comfortable ride and many straight-tail Bonanzas have a yaw damper system, which makes them even more steady.

The somewhat higher control forces are also a safety feature in that they translate directly to rock-solid stability—desirable in an IFR platform. An airplane with relatively high stick-force-per-G control forces is less likely to depart into a spiral if the pilot has to divert attention for a moment or two from the task of keeping the airplane upright and on course. That’s very important in slick, fast singles, as loss of control in IMC still makes the NTSB reports. As usually we’ll equipped, the 36 Bonanza is an autopilot airplane. We’ve flown Garmin’s latest retrofit GFC 600 (and the G1000-integrated GFC 700) autopilots and they are well-matched. But early models could have Bendix, BendixKing or even retrofit S-TEC systems that buyers should pay particular attention to during the prepurchase flight test. These are pricey to maintain, especially with vacuum-driven flight instruments.

When it’s time to disengage the autopilot, landing the 36 Bo can be much easier than in some airplanes, although at extreme forward CG loadings (common when flying solo), it requires some determination to raise the nose in the flare and make a smooth landing. Use the electric pitch trim—all the time. Still, unlike previous research we did on the airplane’s accident record, we were impressed to find few runway loss of control incidents on landing. But keep your guard up—too much speed on touchdown can be a setup for an overrun or loss of control on rollout. And don’t forget the landing gear. Bellied-in Bonanzas are expensive to fix.

Since this is a go-places cross-country machine, performance is respectable, but it’s not blistering fast. Cruise for the normally aspirated 36 and A36 is about 165 knots, with a 1000 FPM-plus initial climb rate. But to scoot up high and run with the Cessna T210N and Mooney 231 crowd, you’ll want the turbocharged A36TC and B36TC. Perfectly rigged airplanes cruise in the 170- to 180-knot range in the middle altitudes. Once over 20,000 feet, the longer wing of the B36TC shows itself, making the airplane a few knots faster than the A36TC, with cruise speeds in the area of 190 knots. That’s not bad, but there’s a price to pay. The turbo Continental TSI0-520s burn fuel—lots of it. Plan on at least 17-18 GPH, to keep head temps under control.

CABIN AND PAYLOAD

Headroom and legroom are barely adequate for especially taller pilots and passengers. It’s good to spread out because with four aboard, it’s a luxury liner, but adding a fifth and sixth person makes things tight. There is a noticeable shortage of baggage space. Some room aft of the third row of seats (watch that CG envelope) was created with the 1979 model. Before that, the only place to stow things was the modest slot between the front seats and the rear-facing center row. There is not enough room to fit six people and six bags onboard, a problem for a family that has kids and needs space for a bunch of stuff.

Up front, panel ergonomics and crashworthiness are good, although at the time the earlier 36 Bonanzas were made, Beech was still using the “backward” or “airline” positioning of the gear and flap switches—with gear on the right and flaps on the left. It wasn’t right or wrong, but just different. But it has led to many inadvertent gear retractions. We do this: When clearing the runway and cleaning up the airplane, don’t touch the handle until you verify (verbally call it) it’s the flaps you’re about to raise. Later models have the switches placed as they are in other airplanes.

When loading the 36, figure on about 950 pounds in the cabin with full fuel in an A36, but watch the aft CG limit when carrying passengers. The A36TC is not a great load hauler; full fuel cabin load is 700-800 pounds. With six 170-pounders in the cabin, each with 20 pounds of luggage, it’s not possible to put any fuel in the tanks and be under gross weight.

The B36TC had a higher empty weight than the A36TC, but gross weight went up by 200 pounds, a net improvement of about one 170-pound passenger. Plan on being able to carry 900 pounds in the cabin with full fuel.

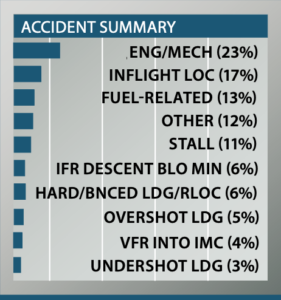

We had to go back nearly 20 years to find 100 accidents involving Model 36 series Bonanzas. We’d like to think that’s a tribute to the airplane, but we’re concerned that it’s because the NTSB may have misplaced accident reports when it switched over to its new, user-unfriendly, “CAROL” search system. Nevertheless, we did find 100 and they did reflect what one expects to see in a clean sophisticated airplane designed for going places fast rather than knocking around the pattern.

Not surprisingly, we saw accidents involving loss of control (LOC) in instrument conditions—half of the inflight LOC events were in the clag. As part of that, there were two inflight breakups after pilots decided that they could fly through thunderstorms. One pilot lost control when changing frequencies in the clouds, got into a spiral dive, recovered and went on to his destination. Upon landing, he discovered that both wings, and their spars, were bent upward.

Six pilots were unreasonably optimistic about their ability to safely descend below approach minimums. Four hit terrain more or less on course, while one diverted we’ll off of the localizer a mile from the airport and smacked into a hillside. One was able to get below the bases some 200 feet below minimums and then announce triumphantly to ATC that he was below the clouds. That was shortly before coming to grief against power lines 118 feet AGL nearly three miles from the airport.

The rate of inflight loss of control and/or stall accidents and hitting terrain after takeoff events was surprisingly high. Many were connected with go-arounds or “high and hot” takeoffs where the airplane is heavy, low and with minimal energy. A number involved what may have been an early liftoff followed by failure/inability to accelerate or climb. Our takeaway is to be very conservative anytime the load is heavy and the temperature high.

There were only three landing gear-related incidents: One pilot selected “gear up” before breaking ground on a touch and go and promptly lowered the airplane to the runway; another was practicing manual gear extensions and didn’t follow the POH procedure to confirm the gear was down and locked—it wasn’t, and it collapsed on rollout; a third was distracted by three boisterous Young Eagles and forget the Firestones. He realized his error in the flare. Attempting to go around, he dragged the left wingtip and pinwheeled off of the runway.

The Bonanza has a reputation for solid handling on the ground so we were not surprised to see only two runway loss of control events and three hard landings. Even with the massive flaps available, five pilots managed to overshoot a landing. Three owners misjudged the approach and hit the ground short of the runway on a night landing.

There were 23 engine power loss events, but the cause of about half—frustratingly—could not be identified. The majority of the rest were improper maintenance, usually failure to correctly install cylinders, and most occurred shortly after maintenance. We saw only one engine stoppage directly related to an owner refusing to do needed maintenance when it was called out to him.

CRASHWORTHINESS

Like others in the line, the 36-series Bonanza is made well. Beech paid attention to crashworthiness and survivability, providing a strong “keel” arrangement from the aft end of the cabin to the nose. It’s tied into a sturdy rollover structure that provides anchor points for shoulder harnesses for all occupants (four-point style for the front seats). There are openable side windows that function as emergency exits. There is no separate door or exit for the pilot. The fuel tanks are in front of the main spar, which lessens their protection in a crash and means that the center of gravity moves aft as fuel is burned.

The landing gear is the same one used for the Baron, where it has to support far more weight. The military T-34 trainer is basically a Bonanza, and as a result the gear had to be subjected to severe drop tests to satisfy the Pentagon. All that structure underneath the cabin also helps to absorb impact forces in a crash.

Another nice thing about the gear is that it’s electromechanical and, if correctly maintained, has proven reliable. Emergency extension is through a simple hand crank located behind the front seats.

The 36 Bonanza also has a simple feature lacking in many aircraft: an easy-to-open “barn door” cowl, making preflight of the engine easy. This is really a safety feature, in our opinion. A popular mod is seatbelt airbags from AmSafe.

The 36 Bonanzas have a much longer CG range than the Model 35 series, although not as long as its competitor, the Cessna 210. Both fore and especially aft loading have to be carefully watched. A pilot flying solo with a full fuel load might have difficulty getting the CG aft of the forward limit. Trying to carry six passengers (reduced fuel is necessary) and any baggage aft of the rear seats may not be possible.

MARKET, MODS

Just as we’re hearing about Cirrus, Diamond and other models, Bonanza sales pros tell us the market demand for nearly every Bonanza model has spiked, especially post-pandemic.

“The market for A36 and G36 Bonanzas is strongest I’ve seen in over 40 years in the business. Prices for well-kept and updated models have risen more than 30 percent in the past year,” George Johnson (“The Bonanza Man”) from Carolina Aircraft in Greensboro, North Carolina, told us. Johnson said his company would typically have over 20 airplanes in its inventory during the beginning of December, but now has fewer than five (and all are under contract) as we go to press at the end of 2021.

Johnson noted that a lot of his inventory of clean Bonanzas comes from longtime customers who may be aging out of flying, or at least are feeling the squeeze of the hardened insurance market.

Moreover, these owners are realizing there may be no better time to sell than now. Some of Johnson’s customers want factory-new G36 models, but there’s a long waiting list due to Textron’s limited production. Johnson says that buyers are drawn to Bonanzas for the same reason they always have been—utility. Curious, we asked why buyers might choose a late-model G36 over a late-model Cirrus SR22 (Johnson sells both brands).

“For a lot of pilots, there just isn’t anything like a 36-series Bonanza, licensed and built strong in the FAA’s utility category,” he said. The aftermarket modifiers also make it easier to get sizable gross weight increases with STC’d systems that kick performance up to an even higher level.

For instance, upgrading the IO-520 to the IO-550 is a popular option when it comes time to overhaul. The STC is available from a wide variety of sources. We have been particularly impressed with Tornado Alley Turbo’s (www.taturbo.com) turbonormalization mod for the A36 that adds 400 pounds to the gross weight and makes the airplane capable of carrying four people 1000 miles at 200 knots.

There are also the popular D’Shannon Aviation mods, and its Raw Power engine conversion kits give Bonanzas a serious shot in the arm. All 1983 and previous models need to have the IO-550 STC and baffle cooling kit to qualify for the 3850-pound gross weight increase. All 1984 and later A36 and G36 models don’t need any upgrades for the increase. D’Shannon’s tip fuel tanks increase the gross to 4010. The company also has a high-performance exhaust kit for IO-550, IO-520 and IO-470N Bonanzas. There are also gap seals, vortex generators and new instrument panels. Visit www.d-shannon-aviation.com for a wealth of available mods and their performance gains.

Arizona-based AmSafe has STCs for seatbelt airbag systems for the Bonanza and you can find more information at www.amsafe.com. There is Approach Aviation (www.approachaviation.com) selling its SmartSpace baggage conversions for pre-1979 airplanes. It gives a much-needed 8 cubic feet of baggage area behind the rear seats, with a 70-pound capacity, while retaining the rear hat shelf. Installation is reported to take only a day.

The best source of current information about mods is the American Bonanza Society. It offers service clinics, training clinics, fly-ins and a good magazine. The ABS is located in Wichita, Kansas (where else?). Find them at www.bonanza.org. In our opinion, we would not own a Bonanza without being a member of the ABS, and neither should you.

OWNER FEEDBACK

I own a 2007 G36 Bonanza that I purchased in 2017. I bought the airplane because I didn’t want the hassle of refurbishing a plane, which I’ve done twice. The 36 is easy to land and makes for a stable instrument platform. I really like the large cargo doors and air conditioning for the hot Carolina summers, where I base the airplane.

I bought the $6500 D’Shannon Genesis Max GWI (gross weight increase) STC, which boosted the gross weight from 3650 to 3850 pounds. I also upgraded to Garmin’s G1000 NXi. The $28,000 upgrade adds significant functionality to existing legacy G1000 systems, and the Garmin Flight Stream 510 wireless capability is a real plus. ADS-B came from a Garmin GTX 345R transponder, which was $5443. Whelan LED strobes, beacons and landing/taxi lights were a $2900 expense.

The Garmin G1000 or G1000 NXi takes a good bit of training to take advantage of the system’s full functionality. I think the King Schools G1000 course is a good launching point, and highly recommend taking Garmin’s G1000 pilot training course. For me, it was a steep learning curve moving from traditional flight instruments and avionics to the G1000.

There are relatively few G36 Bonanzas so finding an experienced Garmin G1000 avionics shop is important. The avionics tech needs to be more of a computer nerd than a typical installer. I have been using Twin Lakes Avionics in Advance, North Carolina. Robbie Greer and his team have delivered quality work on my Bonanza, and Trek Lawler in Garmin’s Aviation Technical Support division has a wealth of knowledge in all things G1000.

My last annual inspection was around $2000, performed by Tradewind Aviation in New Bern, North Carolina. Ricky Hawkins and his techs take good care of my Bonanza, and I have the oil changed every 40 hours.

I find the American Bonanza Society the best resource for my plane and my training. I wouldn’t think of owning a Bonanza without its support. For insurance, I have always used Avemco. As a 73-year-old pilot, Avemco has made it easy to insure my Bonanza. Last year’s premium was $5288 for a $480,000 hull value and $1 million liability.

Last, my favorite upgrade for the airplane is the AC Air Technology remote control tug. It’s a great product and the company’s customer support is super.

Frank Roe – Oriental, North Carolina