It’s a classic beauty with all the bugs already worked out or a maintenance hog demanding an IA certificate just to pre-flight it. Those polar comments (and more) are what you hear when talking about the Beech Model 18.

But owners love them and if you have the right temperament and know how to swing a wrench, the Twin Beech can be a surprisingly affordable large twin.

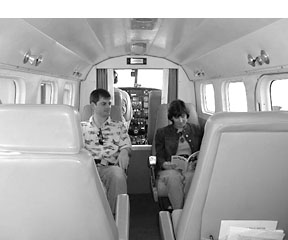

Load it up with eight people, fly 1200 miles with a potty in the back all for we’ll under $200,000? That’s exactly what the 18 can do. As one owner put it, It seems that you must spend over a million dollars to get the same capabilities in anything else. Nothing beats a Twin Beech as a traveling machine.

First, lets get the name straight. Its called a Beech 18 or Twin Beech. All other twins made by Beech were under the name Beechcraft, owners of the real Twin Beech tell us, so when you hear Twin Beech on the radio, you know the model.

The Twin Beech has been an airliner, a trainer for bomber pilots, a freight hauler, fire fighter, fish spotter and hauler and has been pressed into untold missions all over the world over the last 60-plus years. Now solidly into its classic era, this not-so-lumbering workhorse has been discovered by pilots who need to carry people or stuff, who want a solid all-weather airplane or who just appreciate the fact that taxiing up in a Twin Beech puts you over the top for being cool.

Then there’s the sound. Even actor Harrison Ford, when asked about his favorite sound, said, a Wasp Jr. radial engine. Twin Beech drivers get a bit misty-eyed when talking about the distinctive rumble of their engines. But even the gauziest of romances are tinged by reality.

The low point for the Twin Beech seems to have been in the mid-1970s through the 1980s when owners were battered by an AD requiring a strengthening spar strap and recurrent X-ray inspection. Freight haulers were crashing often enough to drive insurance rates higher.

Prices dropped to near Skyhawk levels and fuel burns ranging to 50 GPH didn’t help. Utility and class endure, however, and the 18s popularity is soaring as pilots who recognize its value, nostalgia and utility give a long, serious look.

Before running for your copy of Trade-A-Plane, however, two things demand attention. First, insurance may be the deal-breaker. Although our research shows the Twin Beech to have an accident rate about the same as other twins, the insurance carriers appear to be looking farther back, to the times when most of these airplanes were flown at night, overloaded and in rotten weather, with an accident rate to match.

Also, anyone who wants a tailwheel model faces an uphill battle to insure it without a significant amount of conventional gear time in something bigger than a Champ. The FAA may say you can fly a Beech 18, but the insurance companies will have the last say.

The second issue, addressed in several ways, is the PITA factor. This is a big airplane and its a pain in the ass to fuel it, wash it, move it, check the oil, change the oil and find a hangar large enough. Anyone who doesn’t love doing all this should stay with a more conventional (smaller) twin, because just dealing with the 18 is a large part of the ownership experience.

For many, its simply more time spent enjoying aviation. One owner explained, I love the airplane and I think its the best transportation machine available for anything close to the money. But don’t minimize the PITA factor. You don’t just push it out of the hangar.

History

The history of the Beech 18 is we’ll documented in Larry Balls book, The Immortal Twin Beech. You can see influences of other airplanes in the design of the Twin Beech, but where others fell to the wayside, the 18 flourished, due to a combination of timing and design. The first Twin Beech was introduced in 1938, immediately prior to World War II and it soon was adopted as a trainer for bomber pilots and crews.

The modified AT-11 featured a glass nose and bomb bay doors. Other military versions, the C-45 and SNB-1, carried troops, brass and cargo throughout the war. A particularly sad part of that story, documented in Balls book, was the destruction of hundreds of these airplanes at the end of the war.

Many surplus examples were remanufactured by Beech, with some being converted to a tri-gear configuration. You’ll sometimes see Beech 18s listed with two dates of manufacture-the original and the remanufacture dates.

The first few 18s were fitted with various engines but bolting on the Pratt & Whitney R985, a nine-cylinder, 450-HP radial, truly made the airplane. Owners regularly note deep faith in the 985, even when a cylinder gives out. One pilot experienced a blown jug over the Gulf of Mexico. He flew two hours and changed the cylinder upon landing.

Parts for the airframe and engines can be easily found, which is good, because there’s a good chance the new Beech 18 owner will need a couple of cylinders and assorted parts, depending on the quality and time since the last overhaul.

Freight operators aren’t known for pouring money into their airplanes thus a Twin Beech coming out of such an operation may need a lot of TLC; tender lots of cash. Find an airplane that’s been used for personal transportation, though, and its likely to be as pain- free (or painful) as any other twin.

The D18S entered production in 1946 but even this is confusing because of the remanufactured C45H and SNB military airplanes which were produced after the war and which were similar to new aircraft. The E18S, called the Super 18, followed in 1955, featuring a raised cabin for more headroom.

The G18S (1960) was the first model offered with a factory installation of what was, until then, an after-market modification-a tri-gear configuration. More than 40 years later, the argument continues as to whether the Volpar (tri-gear) conversion ruined a great airplane or made it better.

Certainly, it improved ground handling, but at the cost of increased empty weight (often with increased gross weight, however) and reduced prop clearance. One owner of a milk stool version said: The tri-gear is faster as result of the more streamlined nose. In the air they handle the same. As an old hat, who has over 15,000 hours in all models of Twin Beeches told me, when its 200 and a half, 2:00 a.m. and you break out to a 90-degree 20-knot crosswind in the driving rain, you’ll be wishing you had a tri-gear!

Along the way, the angle of the horizontal stabilizer was changed slightly, resulting in higher cruise speeds. The later models had longer wings, increasing climb rates and decreasing stall speeds. Many of the earlier airplanes have been modified through STCs to have longer and squared-off wings. The final model, the H18, introduced in 1963 was available in tailwheel or nosewheel versions but most buyers opted for the tri-gear option.

Look closely at the logbooks when shopping to see what mods have been made. It would be surprising to find any Twin Beech not sporting at least a few of the hundreds of STCs available. Most notable is the gross weight, which was raised from a pre-war low of 6500 pounds, to 10,200 pounds with various mods. Make sure the airplane you’re considering will carry the load you anticipate.

Performance, Handling

If the mission is to carry a whole bunch of stuff reasonably fast, you aren’t going to beat the Beech 18. First-time 18 pilots are surprised at its good manners-typical Beech. Although it looks draggy, its not and it speeds up quickly when the nose is lowered. While the 18 may be a joy to hand fly, this really is a cross-country machine, as attested to by owner comments.

Reported cruise speeds range from 150 to 180 knots. The variations are due to different configurations as we’ll as a tolerance for higher fuel burns. The longer nose on the tri-gear models is faster, as is the lower cabin of the D18. One tri-gear D18S we travel in routinely delivers 170 knots at a 40 GPH cruise.

Owners usually make the comparison between their Twin Beeches and much more expensive airplanes. They challenge others to find another eight to 10 passenger aircraft with walk-around room (and a potty), that will fly 1000 miles at 170 knots with a purchase price around a hundred grand.

Long range is the ultimate speed mod. On one trip from Baton Rouge to Omaha…we took off behind a King Air going to the same airport. We had eight guys on board. He had seven. We had unloaded the airplane, tied her down and were getting in our rental car when the King Air was on final. We had made no fuel stop, one owner told us.

Fuel burn is nothing to sneeze at-figure 40 to 50 GPH, depending on how hard you run it. With a 318-gallon capacity on some models, that’s a $600 fill-up. Many owners have an STC for running autofuel, although many tell us they takeoff and land on avgas and save the mogas for cruising.

Creature Comforts, Mods

You can find Beech 18s with nothing but a pilot and co-pilot seat and a bare floor or examples with appointments that rival luxury yachts. Soundproofing quiets the cabin significantly and also helps insulate it against the cold.

Manifold heaters earn poor reviews, generally, with gasoline heaters being recommended. Panorama windows on some airplanes make for great views.

Preparing the Beech 18 for a trip often is done the day before, simply because its a major chore. Pilots who want an airplane they can jump into and fire up without breaking stride should avoid this one in favor of a more gentrified spam cam.

There may be no complete listing of all the STCs for the Twin Beech, although we hear that the Twin Beech 18 Society is trying to get as many as they can in order to preserve them in the event that the companies holding them disappear.

Anyone considering buying a Beech 18 should belong to the society: 931-455-1974 or www.staggerwingmuseum.com/18/twinbeech18society.htm. Another site worth looking into is Kyle Larsons www.beech18.net.

Many operators have addressed the Beech 18 signature oil dripping and start-up blast of oil out of the exhaust stacks of these radials by adding rocker oil drains. These drains are an STCd product by John Alden (831-373-7135) which you screw into the rocker drain outlet when you shut down.

Normally, the oil which drains around the rocker boxes collects in the rocker sump and eventually fills the lower rocker covers and can leak through an open exhaust valve and into the exhaust pipes.

These lower exhaust stacks have small holes drilled into them which allow this excess oil to drip out-into the cowl and onto your floor. Hence, the source of the Beech 18 standard oil puddle stains where you park these beasts. Many owners use drain pans to catch the oil.

With rocker box drains, the rocker box drains into a tank rather than collecting in the system and the oil can then be poured back into the oil tank rather than wasted. And better yet, there are no puddles and start-ups are drier, with little chance of an oil hydraulic lock.

There have been several mods for extra fuel tanks. Again, check the airplane youre considering to ensure it has enough fuel for your missions.

Investment, Maintenance

Whether the Beech 18 is an investment can be argued endlessly . The value, as with any airplane this old, depends on getting the right one. To rephrase one owner, you’ll pay now or pay later. You can buy one that’s well-equipped, has engines from the top overhaulers and has all the ADs done. Or you can pay to do it yourself. Either way, you’ll pay.

Once done, though, you have a traveling machine rivaled by nothing this side of the half-million dollar mark. Even a King Air 90 cant carry the load as far. Besides, no one walks out on the ramp to ogle a King Air. You’ll constantly be asked for a peek inside your Twin Beech while no one would mistake a million-dollar Baron for a babe magnet.

But bring your tool box and have fun. If you enjoy tinkering, this is your airplane. Changing the oil is a full days work for a novice like me. A pro can do it in about four hours. Just taking the cowling off and putting it on is challenging at first, one owner told us.

Any Beech 18 with fewer than 10,000 hours on the airframe is practically new, which means that maintenance is vital. The two big ADs are the spar strap X-ray at 1500 hours, and a 1500-hour or five-year teardown requirement on the Hamilton-Standard props. The Ham Standards can be bought for $7500, yellow tagged. The three-blade Hartzell costs $25,000. Several owners tell us they prefer the Hamilton Standard props but the three blade is considerably quieter.

Parts are easy to find, although most owners keep the number of Southwestern Aero Exchange (918-272-9815) on their speed dial. Owner David Warren either has it or knows where to find it if its a Twin Beech part. Time and again owners tell us parts are much less expensive for the Twin Beech than for the typical Cessna, Piper or Beech twin. We don’t know why that would be, but its repeated often enough to be believable.

Oil changes, as noted, are a big job. You’ll buy oil by the 55-gallon drum. Engine access is a dream compared to many tightly-cowled modern designs. Its common for pilots to keep a cylinder and the kit necessary for installing it in the airplane. Interestingly, it may be easier to find a mechanic who knows radials as you get away from the large cities and toward areas where ag planes still run Pratt & Whitneys.

Airplanes which are hangared avoid the corrosion of airframe and props sometimes seen on airplanes left exposed. A well-equipped tool box, greasy overalls, and a willingness to hunt down parts make up the basic maintenance kit for a Beech 18.

An 18 in good shape requires no more maintenance than any other complex twin. It does use a lot of oil, and its big. Access to the engines is generous. If you don’t enjoy spending time with your airplane on the ground, it might, as one previous owner put it, tire you out. Engine overhauls average around $20,000, which is less than on any flat engine approaching 450 horsepower.

Spend as much as you can to get good engines which have been overhauled by reputable shops. Note the time until the next mandatory 1500-hour spar strap X-ray. The X-ray is required to make sure the spar and its supporting strap are still airworthy and costs about $3000 to $3500.

Find a mechanic who knows Beech 18s and fly him to the pre-buy, if necessary. Be realistic about the costs of fuel, oil, time and the hassle factor necessary to keep one of these big birds flying. This is an airplane with a lot of switches, levers, and knobs and you’ll need more than a casual checkout. Find an old Beech 18 pilot and sign up for a bunch of dual.

Owner Comments

The Beech 18 has a reputation for being hard to handle and expensive to operate-both overstated. While the taildragger does present a more difficult machine to control on the ground than most light and medium twins, its not impossible to learn to manage.

The costs of operation are actually cheaper than many other airplanes in its class. Engine overhaul costs are lower than TCM or Lycoming engines, parts are readily available and less expensive and if one chooses to run it on auto fuel, the hourly fuel costs are lower than a Baron.

Expect hourly fuel burn to be about 40 to 42 GPH block to block with cruise fuel burns in the 39 to 40 GPH range-not bad for a machine which can carry eight adults 1000+nm with IFR reserves of over an hour. It takes two Barons to do that. We flight plan 160 knots running 50-degrees lean-of-peak-we have EGT gauges.

Considering the adage that the best airplane for you is the one your wife likes, this is a wifes airplane-walk-around comfort with a potty and it can carry as big a load as you want. Ours has a 10,200-pound gross weight, so baggage is seldom an issue until you have eight adults on board. Even then, weight isn’t the issue as much as luggage storage space. If you don’t mind luggage in the cabin, bring the kitchen sink.

As for the difference in the taildragger and the tri-gear, the taildragger certainly looks better sitting on the ramp. The tri-gear is faster as result of the more streamlined nose. In the air they handle the same. On the other hand, nothing looks like a taildragger Twin Beech taxiing in or sitting on the ramp.

Forget the learning curve, try and get insurance on a taildragger and unless you have many hours of heavy tail wheel time, you’ll mostly get laughter on the other end of the phone. This is unfair, but its a reality.

The many hours of freight-hauling, at night, at gross, with young, low-time pilots at the controls have given the Twin Beech an undeserved bad reputation. Its accident record seems no worse than any other twin, however.

-Walter Atkinson

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

———-

I have owned a C45 since 1990. We use it for pleasure and business and fly it to airshows in Ohio. We purchased the airplane from the Ohio Department of Transportation, who used it for aerial photography. It took about two years to obtain the Standard Airworthiness Certificate through a conformity inspection. We fly the airplane about 50 hours a year, not enough to justify the insurance and maintenance.

I have had my inspection authorization since 1975 and we do all of our own maintenance. I have worked on radial engines in our agricultural operation for over 20 years. Working on the P&W R985 engine is not a problem. The airframe is straightforward, if you have a good basic understanding of light twin-engine airplanes.

I have logged over 8000 hours of tailwheel time and have flown the 18 for about 500 hours. It hasn’t done anything bad to me. If a person has logged a couple of hundred hours in an aircraft like an AT-6 and has multi-engine experience, the 18 would be a piece of cake.

I’m an insurance agent also and insurance can be a problem. Underwriters will look for a lot of tailwheel time and multi time and will probably not consider limits higher than $1 million/$100,000 per passenger.

-Richard Packer

Radnor, Ohio

———-

I flew the Beech 18 in Alaska during my younger days (1975-1979) amassing about 900 to 1000 hours in the airplane. I am still amazed at the performance, load-carrying ability, relative STOL performance and ability to carry a load of ice, with de-ice equipment of course. Carb ice was something a Twin Beech pilot was always looking out for, though.

I never flew anything older than an E model and actually flew the second to last one built.

I don’t think I would want to fly (or ride) in the old models. The upgrades in the newer models are significant. I cant imagine anyone using this airplane as a toy transportation piece. I remember flight planning something like 50 GPH total fuel burn and anything less than a gallon (per side) of oil consumption was a bonus. I’m glad to have had the memorable experiences. This airplane is truly one of the classics.

-Ken Gendron

Seattle, Washington

———-

After 15 years of flying and five or six years of owning a T-6, I decided I wanted a twin. I didn’t have a multi-engine rating, but hey, that sort of thing shouldn’t slow a guy down, right? I decided I wanted a Twin Beech for a number of reasons.

I liked the way they looked, the purchase prices weren’t unreasonable and with a mogas STC, which I had for the T-6, operating expenses were reasonable for me at the time. I was quite current in tailwheel round-motored airplanes and wasn’t intimidated by that aspect. We liked the idea of a big, roomy airplane with a walk around cabin and my wife liked having two motors and of having a classy airplane for traveling.

I swapped some T-6 rides for some Twin Beech rides and found them not unpleasant to fly, nor particularly difficult to land. I did have a bit of adjusting to do in going from a steerable tailwheel to a non-steerable tailwheel but that just required a little practice.

I found one that had never been a freighter, didn’t have a cargo door and had a nice looking executive interior and a working retractable tailwheel. It was a 1946 D-18S, painted in a military C-45 scheme with a painted underside and polished top.

Mistake number one. I will never again own a polished airplane. One the size of a D-18 is a particular challenge to keep looking good. The engines were mid-time, the avionics were acceptable for IFR and the airplane looked good. I bought it.

Buying insurance was a challenge. Somewhere there is probably still an Avemco agent who laughs at me. I would have found it difficult to buy insurance for any twin with only 10 hours of multi-engine time, but the insurance companies were most reluctant to write it at all for a Twin Beech.

I finally acquired it through the carrier who had my T-6, with a number of restrictions. I had to get 25 hours of dual and 10 hours of solo before carrying passengers. I’m sure the requirements would have been even more stringent if I hadn’t had so much high-performance tailwheel time.

I enjoyed the way the airplane flew. I had no problems flying or landing the airplane, ever. It was honest with me and never tried to bite me unless I invited it enthusiastically.

We flew it to Grand Cayman, took it to quite a few airshows and many places throughout the southeast. I’ve often said Id like to fly one again but I’m in no hurry to own another one.

The problems: The airplane was in good shape cosmetically, but had never been restored. It had always been fixed when something broke, but never systematically gone through and had parts that weren’t broken replaced.

I didn’t do a very good pre-buy, in retrospect. Many hoses were dry and beginning to crack, pumps-fuel and hydraulic-were worn out and I found out at the first annual that one engine was about to let go. I had to buy a motor due to metal in the sump-with part numbers readable- but it didn’t quit on me. I’ve got no complaints about the Pratt & Whitney Wasp Jr. or Wasp series of engines.

I replaced one mag after the old one packed it up coming back from an airshow and I replaced and calibrated one voltage regulator. It got to the point that I was neglecting the T-6 to do maintenance on the BE-18 so that it was flyable on the weekends.

The good news is that most parts were readily available from salvage yards and other sources and there are still plenty of folks around that know how to service the systems.

Advice to a prospecting purchaser includes the usual good pre-buy by someone familiar with the type, not that specific airplane. He should check the overall condition of the rubber parts and check for corrosion under those cockpit side windows in the D-series, in addition to the usual things any good pre-buy covers. The time on the spar strap and spar X-Ray should also be checked, of course.

Be prepared for 50 GPH fuel burns and as much as 2 GPH of oil consumption and the aggravation of having to climb up on the wings to fuel the five or six gas tanks. A four- to six-foot step ladder is a required piece of equipment for traveling as is a good toolkit. I fixed a rack back in the old radio bay to carry mine.

The airplane just got to be too much trouble for me to maintain on my own, with an AI who came to help me work on it. It eventually made me tired so I sold it and bought a Twin Comanche

-J.B. Stokley

Opelika, Alabama

———-

I got my multi-engine rating last year in my own Twin Beech. This particular Beech 18 was a D-model, serial number 45. It was built in January of 1946, one of the first post-war Beech 18s.

The previous owner made major changes and made the airplane beautiful. He put the single-piece windshield in, which is wonderful for visibility and noise reduction, but lacks the charm of the original faceted windows.

He put the Percheron tailwheel strut on, which effectively raises the tail, increasing the forward visibility for taxiing. He installed the Horner wingtips, increasing the max gross weight significantly.

The first thing to do to get ready for a lesson was to dress the part. Wear the clothes that will regularly get grease on them. By the time you’ve unhooked the tow bar, crawled around under the airplane to drain the five fuel sumps and pulled the props through, you’ll have oil on at least one sleeve.

I can attest that the Twin Beech, with full fuel and five people on board, will climb out on one engine on a 115-degree day. Really. All 8400 pounds.

The Twin Beech is a joy to fly. The controls are we’ll balanced, the 450 HP Pratt & Whitney R985s have that great sound and you get to tell ATC that you’re a Twin Beech. As I was told on more than one occasion, its a Real Airplane, not some Reynolds Wrap, Para-Lift, Land-O-Matic soggy Cessna.

-Elizabeth D. Roberts

Decatur, Texas

———-

A nice fellow at the Twin Beech Association convention let me put 0.5 on his airplane in October 2000. That sold me. By March 2001, I had an SNB-5 under contract. It was located in Bavaria, last flew in 1995 (five hours); and had less than 50 hours since 1980.

A Twin Beech can be had for $75,000 to $120,000-less than half as much as many lesser brethren. (Note: A general rule of thumb is that an -18 owner wont be happy until he has $250,000 in the airplane. That’s true whether one buys an -18 for $50,000 or $200,000.)

As for maintenance, an owner will get his moneys worth as long as he enjoys spending some time with his hands greasy and with parts of the engine lying on the ground and so on.

Changing the oil is a full days work for a novice like me. A pro can do it in about four hours. (Just taking the cowling off and putting it on is challenging at first.) In Chicago, that means an oil change costs $240-not counting the cost of the oil.

All -18 owners I have spoken with tell me that after the initial period of ownership, the airplane will settle down and the maintenance headaches drop off quite substantially.

I cannot say from experience that that is true, but that story is so universal that I guess either (1) it is true or (2) owners learn to love the problems.

Either way, every owner I know loves this airplane and knows it to be the unsung jewel of the American fleet.

-Jonathan Arnold

Chicago, Illinois

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Twin Beech Accidents: Groundloops and Engine Failures.”

Click here to view “Resale Values, Payload and Prices Compared.”