Aircraft insurance underwriters might demand hefty premiums for some high-performance taildraggers, but the tame Cessna 120/140 series could put them at ease. With the right initial training, a focus on staying current and keeping up with maintenance, these little Cessna classics are decent airplanes for pilots stepping into the world of tailwheel flying.

The reality is the qualities that made the airplane popular in the late 1940s are still present. These days, what little they give up to Piper’s Cubs in panache, they more than make up for in reduced acquisition costs (although prices are up on nicely restored models) and arguably more-forgiving handling qualities.

Searching the market? Here’s what to expect.

A WALK BACK IN TIME

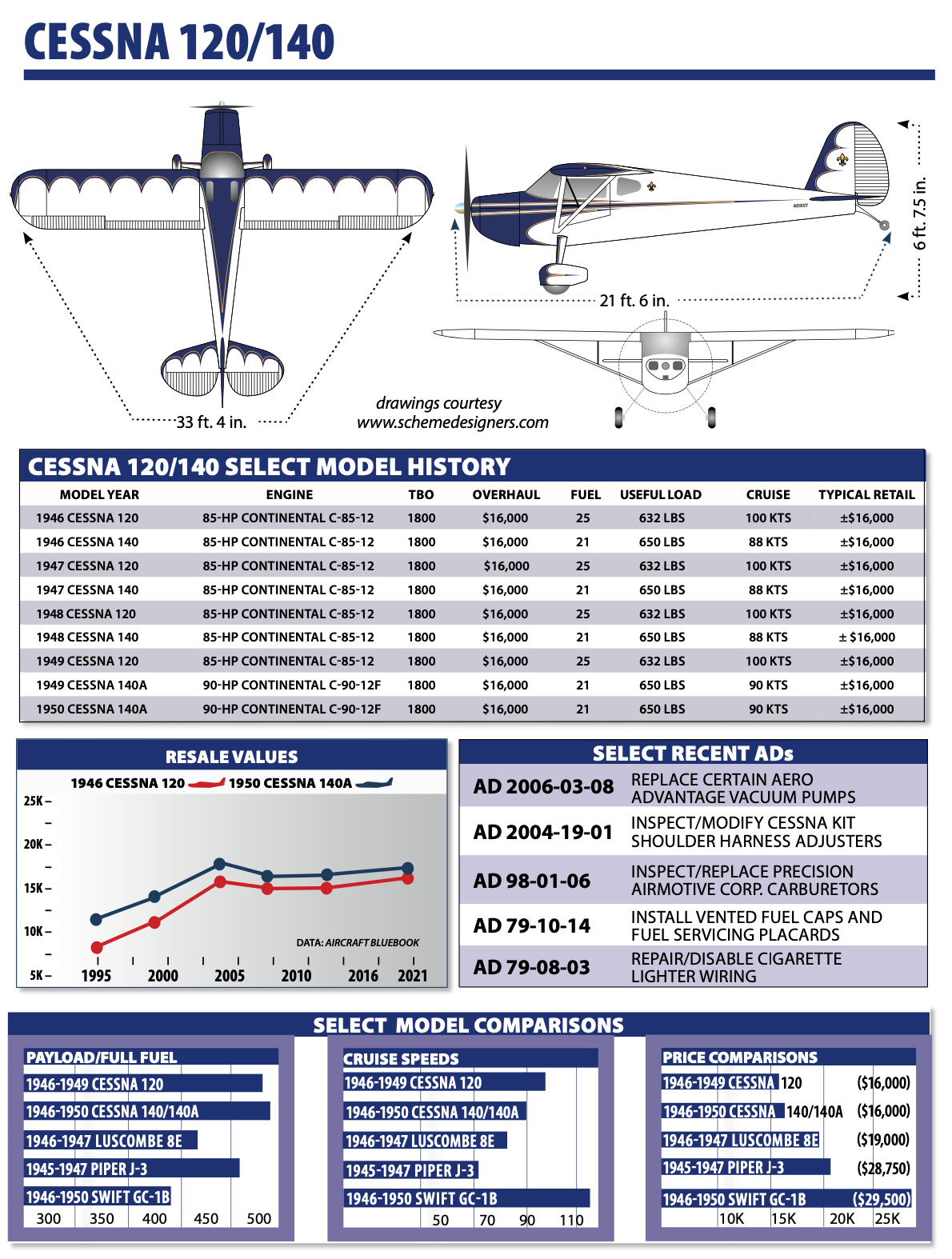

Some think the Cessna 120 came first, but the first of the Cessna models to be built in volume was the diminutive Cessna 140, followed a month later by a stripped-down version called the 120. At the time, the Cessna 120/140s were perfectly serviceable and practical two-place airplanes. They were reasonably priced to buy and economical to own. There was a reason for that.

During WWII, tens of thousands of Americans were either taught to fly by the U.S. military or were exposed to the routine use of air transport to cover long distances quickly. Aircraft manufacturers naturally assumed this fertile crop of newly released soldiers, armed with the recently enacted G.I. Bill of Rights, would generate a sales boom of staggering proportions.

It did. While it was of far shorter duration than even the most pessimistic forecasts, huge numbers of new airplanes were manufactured. Piper was building Cubs and, soon, Cruisers and Pacers pretty much as fast as it could. With a few exceptions (Beech’s Bonanza or the Ercoupe, for example), most offerings were tailwheel machines. So equipped, the Cessna 120/140 was easy to own. Although they all initially had fabric wings, they were made mostly of metal, avoiding the periodic need for re-covering. That’s another checkmark in the plus column for owning one today.

The 120’s model history is rather short, since it was produced only for four years, from June 1946 through May 1949. Since Cessna had the training market firmly in its sights, the 120 initially sold for a mere $2695. That amount is equivalent to just under $30,239 in 2021 dollars. Try to find a new, FAA-certificated, mostly-metal trainer for that kind of money today.

Cessna made the 120 about as simple as airplanes get, with side-by-side seating, yokes rather than sticks, no flaps and no rear window. Because it was cheaper than building cantilever wings, Cessna—which had never put a wing strut on an airplane since it started production in 1927—hung struts on the 120/140 series, forever changing the public’s perception of the product line.

Standard equipment did not include an electrical system, although a generator was available as an option. The International Cessna 120/140 Association tells us that none left the factory with one; however, most 120s have an electrical system these days.

To go even more upscale, Cessna followed the automotive industry of the time and offered a “luxury” version, dubbed the 140. It came with flaps, an electrical system, fancier seats and a pair of rear windows on either side of the fuselage (but not the wraparound, Omni-view configuration that later became standard in Cessna’s single-engine line).

That was the company’s entry-level, post-war lineup. These airplanes sold we’ll and although there was demand, there was also competition. For example, Piper was building acres of Cubs. Other companies—Taylorcraft, Aeronca, Globe, ERCO and Luscombe—also offered two-place airplanes and, although Cessna was shoving some 30 airplanes out the door daily in August 1946 and eventually made some 7000 120s and 140s, by the end of 1946 the bloom was off the rose. Sales dropped annually. In 1949, the company realized it needed to revamp the platform to stay competitive.

In that model year, Cessna built its last 120 and brought out the 140A. The revised model came with a redesigned, all-metal tapered wing with a single strut, presaging what was to come from Cessna’s singles. The strut replaced the two-piece struts of its predecessors, with a single attach point at the fuselage and two attach points under the wings.

Also, the 140A offered a choice of engines: Available was an optional 90-HP Continental four-banger in place of the 85-HP engine common throughout the 120/140 series. At a glance, the easiest way to recognize the 140A is by the single strut. Despite its changes, the 140A didn’t sell as we’ll as the 120/140. Only about 500 left the factory before the line was shut down in 1951, after which Cessna turned to other models, including the 195.

But Cessna wasn’t through with light singles, regardless of whether the 140A’s demise resulted from competition or a tired market. In 1959, Cessna hung a nosegear on the basic 120/140 airframe, creating the most successful trainer of all time: the Cessna 150. Thousands were built and many a pilot owes his or her basic skills to the 150 and its successor, the 152. In turn, the 150 owes its existence to the 120/140 line.

CONSTRUCTION, SYSTEMS

As noted and in contrast to Piper’s Cub, the 120/140 is an all-metal design, at least for the fuselage. The skins are riveted over ribs in conventional monocoque construction. Even for the 1940s, this was nothing special; all-metal Luscombes were on the market before the war. But it also was durable and easy to fix, especially by the hordes of aircraft mechanics trained by the military during WWII. Early 120s had fabric-covered wings, a “feature” carried over to the 140, as well. When Cessna upgraded the line to the 140A, the wings were all metal. The additional, aft-cabin windows and single strut were retained. Many of the older airplanes originally delivered with fabric wings have been converted to metal.

While there’s certainly nothing wrong with fabric wings, they do require care and maintenance. If the airplane will be a ramp dweller, we think the 140A—or at least an airplane with the all-metal-wing conversion—is the better choice. Oddly, buyers may also find a few 140s sporting 120 wings, i.e., a 140 without flaps. On finding one, we’d be very interested in learning more about the airframe’s damage history.

No matter the model designation, systems are stone simple. The fuel system includes a 12.5-gallon tank in each wing, connected through a left-right-off valve. Later models had a “both” position and a fuel-tank crossover line. When originally delivered, airplanes with electrical systems had generators and a few flying have them still. These days, the better setup is an STC’d alternator conversion.

As far as engines go, the 120/140 came from the factory with only two choices. The 120/140 has the 85-HP Continental C-85-12 while the 140A got the 90-HP C-90-12F, all with metal propellers. Even a cursory glance at today’s market, however, reveals all manner of engine upgrades, including the Continental O-200 used in the Cessna 150—said to be a bolt-on conversion—and the O-235 used in the Cessna 152. At least one STC involves installing an O-200 crankshaft and cylinders to a C-85 crankcase.

While these newer engines may improve performance, the real reason for having them is serviceability. While parts remain available, the older C-85 and C-95 engines grow ever more difficult and expensive to support.

As noted, the 140s have flaps while the 120s don’t. Do you need them? Probably not. One owner wrote a few years ago to say he considered the 140 flaps to be a “joke.” In any case, these airplanes fly so slowly that the benefit of flaps is questionable. Any pilot worthy of the title should be able to put one of these into a pea patch without need for flaps.

CABIN, AVIONICS

Let’s start at the instrument panel.Although there’s not much there, these little Cessnas were generously equipped compared to basic airplanes from the same era. Think utilitarian—these are casual local-area cruisers, for the most part. Still, it should come as no surprise some owners have jazzed them up with GPS and other goodies. Plus, there is enough space for basic IFR instruments (yes, even small-screen EFIS) and modern stack-mounted avionics.

In fact, there’s no reason these aircraft, if properly equipped, can’t be flown in a little light IFR. Most aircraft of this vintage sport exterior venturi horns for vacuum, although some have vacuum pumps, too, depending on the engine. Although some think it’s insane to fly a venturi-equipped airplane in actual IFR, we don’t see the problem. The venturi might actually bemore reliable than a pump, as long as you can keep it from freezing up. Sure enough, heated versions are available.

Moving into the cabin, you’ll find primary controls consist of a pair of side-by-side yokes grouped in the center of the panel. Anyone with passing familiarity with a Cessna 150 knows how cramped the seats and interior are. The Cessna 120/140 is no better; the seats are 1940s-style bench designs and both shoulder and legroom are limited.

Taller pilots may find their knees colliding with the yokes, while short ones may need a pillow to reach the rudder pedals. The seats are fixed in place and, unlike more-modern fixed-seat types, the rudder pedals do not adjust fore and aft. As one result, we’ve seen a few of these airplanes modified with later-model Cessna 150 seats.

Visibility from the cockpit is marginal, at best. It’s not bad out the side windows, but 120s without a rear-window modification essentially blind the pilot from getting a good look at what’s behind and to the sides. The 140s, with their rear windows, are a bit better. Meanwhile, visibility out the front isn’t up to modern standards, either.

Trainers like the 152, Diamond Katana or even the Piper Tomahawk excel in this area in large part thanks to their tricycle gear. But the 120/140’s taxi stance is not so sharply pitched a pilot can’t see over the nose; the short cowling and somewhat flatter deck angle are a real plus compared to other tailwheel airplanes.

You don’t need to sashay down the taxiway making S-turns to keep from creaming another airplane coming the other way. But it might not be a bad idea. One thing that aids ground handling is toe brakes, a vast improvement over the heel brakes found in the typical aircraft of this vintage.

Owners often complain about one 120/140 shortcoming: cabin noise. The cabin is small and the engine is nearby, with the exhaust dumped overboard very near the occupants’ feet. The results can be deafening—perhaps more so than in contemporary types. We’d consider an active noise-canceling headset mandatory (but we do, anyway).

Finally, it should come as no surprise that cabin heating and ventilation in the 120/140 are not up to modern standards. Owners say it is adequate, however, and many airplanes have been fitted with vents in the wing and/or blast vents in the side windows to improve airflow in hot weather. The front cabin windows are openable for ventilation during taxi.

PERFORMANCE, HANDLING

Even though the 120/140 does better than other two-seat tailwheel airplanes of similar vintage, owners tell us performance can best be described as “thrifty.” A pilot can expect to see between 95 and 105 MPH true from the 85- or 90-HP engines Cessna installed while burning about 5 gallons an hour. That’s in keeping with a slightly faster Cessna 150 burning 6 GPH. Results from installing a more modern engine like an O-200 or O-235 predictably push up cruise speeds.

Regardless, this is not really a traveling machine: A cross-country of any length will take most of the day. If several states must be spanned, plan on a couple of days, or find another solution. Too, getting to and staying at altitude is another challenge. There simply aren’t many of the 85-to-100 horses left at any altitude above 10,000 feet. Climb rate in these airplanes is about what you’d expect: adequate at mid-weights but somewhat anemic at gross.

Max gross, by the way, is 1450 pounds for the 120/140 and 1500 pounds for the 140A, with a typical useful load of 600 to 650 pounds. Obviously, a load-hauling, utility airplane the 120/140 isn’t. Perhaps not so obvious, however, is the two airplanes are too heavy to be considered a so-called “legacy” light sport aircraft, or LSA. Since 1320 pounds is the max gross weight for an LSA (1430 for a seaplane), the 120/140 miss the cutoff maximum weight by a fair margin (along with contemporaries from Aeronca, Luscombe and Taylorcraft, to name three).

For its size, the airplane has large elevator and tail surfaces, which probably account for its good crosswind characteristics on both grass and paved runways. As post-war tailwheel airplanes go, despite the RLOC accident record outlined on the sidebar on this page, the 120/140 handles quite well. Ailerons are brisk and crisp—if not aerobatic in roll rate—and pitch is a bit lighter than expected from the typical Cessna.

Overall handling is quite forgiving, with few bad habits in the air. Wing dihedral gives it stability the J-3 Cub lacks, and the 120/140 does not have the massive adverse aileron yaw of the Cub or Champ.

As tailwheels go, it is not as forgiving on the ground as a J-3 Cub, but contemporaries from Luscombe and the like generally are considered “touchier.” Of course, all tailwheel airplanes are ditch lovers compared to tricycle-gear airplanes, which explains why the 150 became so popular.

Landing a 120/140 is not especially difficult. The fact that it has better visibility over the nose than most airplanes of its ilk helps. So, too, does the side-by-side seating, which obviates some limitations, like the need to solo it from the rear seat. Being relatively light, it does have a tendency toward ballooning on landing if the mains are forced on at too high a speed. But the airplane will happily do three-pointers or wheelies all day if the pilot’s skills are up to par.

Because it doesn’t have the option of placing much weight rearward, the airplane has a tendency to nose over. Owners say it’s likely that any 120/140 on the market has a noseover or two in its history. That’s no big deal if any needed repairs are done correctly. But nosing over is a big enough “deal” in this type that many have been equipped with “wheel extenders”—spacer blocks on the main gear legs that move the wheels a few inches forward. This reduces the tendency to nose the airplane over and if you’re looking at an example that doesn’t have the extenders, we think it’s worth considering them.

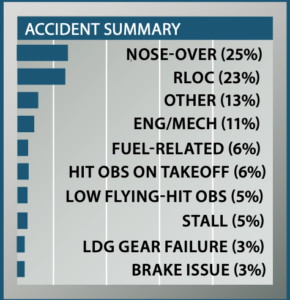

We’ll start our review of the 100 most recent accidents of the Cessna 120/140 series by praising the airplane and its pilots/owners for what we didn’t find.

There were no VFR into IMC crashes. There were only two carb icing events that led to an unintended landing and, at 11, the number of engine/mechanical power losses was low.

There were five accidents involving a stall, lower than we would expect for a modestly powered airplane that sees service in the backcountry.

Unfortunately, not all 120/140 pilots were aware that airplanes with small engines require respect in takeoff planning. Six were able to get their machines off the ground but could not climb over obstructions.

In one case, an instructor and student decided to do a stop-and-go on a 2000-foot grass strip. They stopped at the 1000-foot point. As an aside, this was August in Oklahoma. The go portion resulted in a liftoff, followed almost immediately by snagging the fence at the end of the runway, ending the flight.

We noted the determination of the pilot who got himself into PIO after touchdown on a short runway. He went around late and could not climb enough to clear the fence at the end. Still airborne, and not willing to give up, he found himself facing a line of trees. He stalled turning to avoid them.

There were only six fuel-related accidents. One involved a mis-installed fuel selector and three were pilots who ran a tank dry and didn’t successfully switch tanks. One pilot washed his airplane and didn’t sump the tanks. On the subsequent takeoff roll the engine sputtered and lost power. Shortly thereafter the engine regained power and the pilot elected to press on. Sadly, we could write this one with a rubber stamp—once in the air the sputter returned, followed by silence as the water in the fuel finally, and fully, stopped the engine.

We saved the bad stuff for last. The risk for a 120/140 pilot is highest when the wheels are touching the ground. There were 23 runway loss of control (RLOC) accidents—not bad for a tailwheel aircraft. The real bad stuff is that separate and distinct from the RLOC events there were an amazing 25 nose-over accidents . Those were due to, usually, heavy braking or trying to land or take off on a soft surface. Plus, almost all of the RLOC crashes wound up with the airplane nosing over—there was a staggering total of nose-over events—43. To us that’s huge—nearly half of all 120/140 accidents culminated with the airplane upside down.

We think that shows an issue with landing gear geometry that must be respected. And, ordinarily, few RLOC accidents produce serious injuries, but two were fatal because the owner had not followed guidance to replace the aluminum center seatbelt bracket with one made of steel. The aluminum broke, leaving the occupants unrestrained during the impact.

In addition, there was at least one RLOC-into-nose-over that was fatal because the pilot was going so fast when he lost control on his wheel landing that the flip over was not survivable. Extra speed on final in a tailwheel airplane is never a pilot’s friend. That’s doubly so in a 120 or 140.

MAINTENANCE, ADs

Owners buy vintage airplanes for many reasons and one of them is low cost of operation. While that’s not true of every post-war spam can out there, it’s certainly true of the 120/140. Despite post-war competition, it occupies that sweet-spot niche of having been produced in large enough numbers to provide a good parts reservoir while not being so rare it has classic collector value.

The stock engines can be kept perking along with effort and/or upgraded with newer versions, the latter being our preference. Try to find an airplane with an engine conversion already done.

Other than engine overhaul, the major cost for a 120 is re-covering the wings, if they’re still fabric. Depending on the fabric and whether the airplane is hangared, re-cover intervals range between seven and 20 years. Metal wings are, of course, heavier than the fabric versions by about 30 to 40 pounds. But most owners consider the penalty worth it in reduced maintenance costs and, in any case, these airplanes aren’t bought for the massive load-hauling capability.

As do all airplanes, the 120/140 models have some weak spots. Here are some things to look for:

• Look for damage in the lower door posts, near the strut attach point. This critical structural member may be damaged by rough field operation, groundloops or corrosion.

• Corrosion in the carry-through spar can be a problem. The cabin skylight leaks water into this structure, and years of moisture will take a toll.

• Cracks in the tail structure and rear fuselage. Those familiar with the 120/140 tell us the airplane’s tail is the weakest part of the design. It’s especially vulnerable around the tailwheel attach point. This is repairable, but make it a condition of the sale during prebuy.

• Landing-gear boxes take a beating on all Cessnas and the 120/140 is no exception. The gear box—the support structure for attaching the landing gear to the fuselage—may have taken abuse from pilots over the years, thanks to hard landings and maybe even a groundloop or two. The box can be inspected from the outside by removing an inspection plate in the cabin floor.

• Broken tailsprings are fairly common. Check to ensure that the steel leaf-type tailwheel spring is still springy but not saggy. A broken spring will cause complete loss of control on landing and could do major damage to the airplane, particularly the elevators. Even if the springs look good at the time of purchase, they should be inspected regularly.

The list of ADs that apply to the Cessna 120/140 is quite long—more by dint of age than in any serious shortcomings in the aircraft. Some of the ADs are absolutely ancient, dating back to the late 1940s, when the airplane was new. Many are shotgun-type ADs that apply to the engine and may or may not require compliance in the model 120/140 at hand. One of the most recent applies to the Lycoming O-235 engine, calling for inspection of the crankshaft.

MODS, TYPE CLUBS

The list of mods and STCs for these airplanes is nothing short of awe-inspiring. The International Cessna 120-140 group maintains an exhaustive list on its website, including contact information. The fact that the airplane has been the subject of so many mods speaks we’ll of both its basic design and that it remains flying in large enough numbers to make such mods economically worthwhile.

Some of the more interesting mods include the aforementioned engine upgrades, including the Lycoming O-235, metal and fiberglass coverings for the wings, alternator kits to replace the older generators, improved brakes and instruments, autogas STCs and even approval to install an engine-driven vacuum pump in lieu of a venturi.

As for groups, the International Cessna 120-140 Association maintains a terrific website and support network. It can help with buying advice, parts and other support. Find them online at www.cessna120-140.org.

There is also an active 120/140 Facebook page worth visiting.

OWNER COMMENTS

We have owned a 1950 Cessna 140A for two years now. This ownership got started with my son expressing an interest in flying. I have almost 7000 hours flying all types of single-engine piston airplanes, mostly complex high-performance types, so he had plenty of flying exposure. My latest transportation is a Mooney Ovation, which I use frequently for trips when I need to be somewhere. However, I was convinced my son should get his initial training in a “real” airplane, one with the steering wheel on the tail. I arranged for some time in an Aeronca 11C Chief with a local owner, and engaged a local CFI with a lot of taildragger experience to fly with him. My son was soon hooked. I flew the Chief a couple of hours too. I had about 25 hours of taildragger time in various types, including 120/140s, but was unimpressed with the 65-HP Chief’s flying characteristics.

After some discussion with my son, we decided to invest in a suitable airplane for his initial training. After discussions with the CFI and our A&P, along with my previous experience, we decided that the 140A was the best choice of a good training platform, along with it being efficient to maintain and operate. Our local mechanic agreed to help find a good one for us, and we ultimately found a suitable airplane in Minneapolis. The previous owner agreed to deliver it to Texas for us as long as I paid for fuel and a return airline ticket. After a few local flights in the 140 of up to 90 nautical miles, it was a good call. The Mooney has ruined me for traveling long distances that leisurely.

We were now the proud owners of a 140A. It came with 3200 total time and 850 hours on a field-overhauled engine. This was a noticeable upgrade from the Chief: 30 percent more power, better brakes and better rudder authority. Overall, it’s a great taildragger for training and having fun. My son reported that the upgrade to 90 HP was instantly obvious, especially with an instructor onboard. One key characteristic of the 140 is a relatively long distance from the CG to a decent sized rudder, which makes for very effective control, easily taming the ground handling of any taildragger. On the Cessna, I seldom use any brakes at all when landing or taxiing.

Stalls are definite, but predicable. The 140 is an effective short-field performer, both for landing and takeoff. The flaps have three settings and are effective to help landings, especially wheel landings. For regular landings, I use two notches of flaps and at a real short field, three notches. One notch can shorten takeoff ground runs if needed. Any airport in my area is suitable for landings. Last summer we even mowed a 1600-foot strip in a hay field next to my house and played with landing there—lots of fun. Again, the 140 gives the pilot very effective rudder control, making ground handling easy for an attentive pilot.

The simple systems and engine have meant low maintenance costs, and the most expensive was new tires. It will just run and fly with few issues and it is always ready to go. It checks all the boxes of a more modern airplane: electric start, all-metal construction, good toe brakes on both sides, few ADs, well-balanced controls, effective flaps and it look good too. I highly recommend this little airplane for simply having fun, or as time builder for new pilots. The 140 was purchased for training my son and the goal was an efficient time builder to teach good piloting skills before moving up to a Cessna 172 for final training. This has worked well.

In the meantime, I came to realize the joy of a simple runabout—just-for-fun flying. Frankly, the big Mooney is not fun to “just fly around” because to me it feels more like a business meeting airplane.

The small Cessna is just for kicks. Now I am always looking for local, unusual flying destinations, or even an excuse to just buzz around the pattern. I highly recommend a good 140 for any of these reasons.

Ted Gribble – East Texas

I love this airplane! The Cessna 120 is my first airplane and I’m a relatively new pilot. It makes a great first airplane that is capable, easy to fly and easy(ish) on the wallet. I’ve done all my own maintenance under the direction of my IA and made quite a few upgrades.

With the addition of some solid axles and small tundra tires, this thing is a load of fun out in the desert and operating off airports. My airplane has the O-290-D engine, which makes it a great performer.

Tamer Abubakr – via email

We became joint owners of a 1946 140 and found it inexpensive to own, maintain and operate. Fuel burn runs 4-4.5 GPH at 105 MPH (not knots).

Ours came with a metalized wing, which we dislike because it reduces useful load by 50 pounds. The original Goodyear brakes were maintenance intensive and moderately effective, but good on grass strips.

The original straight stack exhaust, no muffler, on the airplane was just plain loud. The Eisemann magnetos gave a strong spark but were heavy for such a light aircraft. The airplane came to us with the horizontal stabilizer mod, which reinforced the horizontal stabilizer spar.

The Cessna 140 is a lot of fun to fly because you have to fly it—it doesn’t fly itself. As a tailwheel machine, takeoffs and landings require full pilot attention. It requires prompt and timely use of the rudder—wooden feet need not apply.

Tom Tann – Michel Litalien – via email