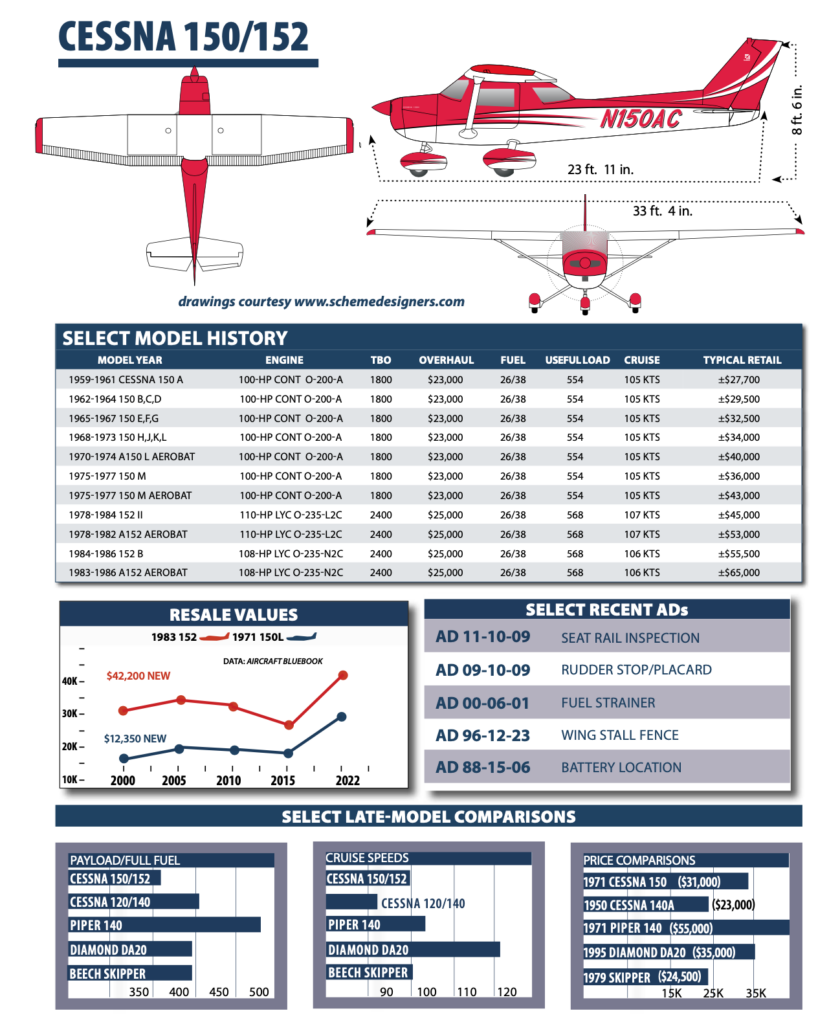

Consider that in the early part of 2016, a 1979 Cessna 152 II had a typical retail price of $24,000, according to Aircraft Bluebook. At press time (January 2022) the same airplane is shown at $40,000, and there’s no sign of a downward price trend. Moreover, we’ll cared for 150s and 152s with good engines, new avionics and spiffed up paint sell for quite a bit more.

But inflation aside, pilots love the venerable two-place tricycle gear Cessna for the same reasons they always have. These are simple and reliable trainers that are easily supported at most every maintenance shop, plus they don’t cost a fortune to own. But these are old airplanes, so shop carefully, do a good prepurchase eval and be prepared to drop a premium on the good ones.

MODEL HISTORY

Piper owned the market during the 1940s, but that was all to change when Cessna created the 120 and later the 140, which stayed in the model line until the early 1950s. Although only hardcore Cessna aficionados know it, the Cessna 172 actually predates the Cessna 150, which first appeared in 1959.

By modern standards (especially when eyeballing sleek LSA models), the first 150s look downright frumpy, with their squared-off tails and a turtledeck-style fuselage, with no rear window. In 1961, the first of many changes in the model began, starting with moving the gear struts aft two inches, curing the airplane’s tail heaviness. Ten years later, tubular gear legs with a wider track were added.

In 1964, the rear window appeared and, of course, it needed a snappy marketing moniker, thus was born “Omni Vision.” The stodgy straight tail went away in 1964, replaced by the swept-back tail, giving the airplane a more rakish look.

The overall dimensions of the airplane haven’t changed much, but its max gross weight has. The 150 began life as a 1500-pound airplane, but by 1978, the gross weight had been bumped up to 1670 pounds for the 152. For a two-place airplane, that’s a big hike but, as is usually the case, there wasn’t much payload gain due to rising empty weight.

If you’re like some of us here at the magazine who learned to fly in a Cessna 150, you remember a cramped dwelling that had you sitting shoulder to shoulder with your instructor. So it goes in a 150/152. Cessna tried to help and bowed the doors out slightly, and also trimmed the center console to provide more legroom for taller pilots. Still, you wear these airplanes.

The baggage compartment was also enlarged several times and one option included a rear child seat. The baggage area could accommodate up to 120 pounds of kids and/or bags, so it was suitable for a toddler and a day bag, but little else. But for a small airplane, the baggage area is rather generous and easily accessible for an instructor fishing for a chart or a hood.

In 1975, a larger fin and rudder were added and before that, electric wing flaps were installed. Previously, the flaps had been manually operated and some pilots complained that electrics were a step backward. We had one electric flap failure in our time with the airplane and remember landing it clean on tight pavement before a mechanic swapped the flap motor.

CONTINENTAL TO LYCOMING

Around 1959, the 150 first appeared with a 100-HP Continental O-200, a reliable and easy-to-maintain engine that matched the airframe nicely. When 80/87 fuel began to fade from the market in 1978 (displaced by 100LL of course), Cessna switched to the 110-HP Lycoming O-235 that provided more power and boosted the TBO from 1800 hours to 2000 hours and eventually 2400 hours. The 152 II was born.

As the 150 morphed into the 152, there were other changes, including a 28-volt electrical system, a one-piece cowling, a McCauley gull-wing prop, an oil cooler and redesigned fuel tanks. All of the worthy changes netted about 40 pounds more useful load than the original Cessna 150 had, but fully 60 pounds less than a 1948 Cessna 140 could haul. The airplane’s performance was about equal to the 150 it replaced, but the engine was susceptible to severe lead fouling when burning 100LL and the 28-volt electrical system was a nuisance, especially later on when owners started upgrading the avionics out of the stock ARC Cessna radios.

Also, the 152 turned out to have some significant warts. Early models were hard to start because of weak spark and lack of a priming plunger. Cessna added impulse coupling on both magnetos to improve this, plus direct priming for each cylinder. Mechanics complained about having to remove the prop to decowl the engine so Cessna added a split cowl. In 1981, the Lyc got a spin-on oil filter as standard, rather than the old rock screen. In 1983, Cessna and Lycoming tackled the lead fouling issue by replacing the O-235-L2C engine with the N2C variant, which the model had until it was discontinued in 1985.

Except for troublesome starter drives, the Continental O-200 used in the Cessna 150 was a reliable and robust engine that could be counted on to make the 1800-hour TBO, if not beyond. These days, plan on dropping $25,000, on average, for an overhaul done right.

The Lycoming O-235-L2C was supposed to achieve three goals: Solve the O-200’s lead problem, boost power a bit to increase the payload and offset the 15 percent gain in empty weight and last, reduce noise. The higher compression O-235 Lyc delivered its 110 HP at 2550 RPM rather than the O-200’s 2750 RPM.

Did Cessna hit the mark? Not really, say some operators with both airplanes on the flight line. In its favor, the Lyc had no starter problems, but if the engine/prop was quieter, you’d hardly notice. Owners complained about high parts prices for the O-235—including pistons and valves, the latter being sodium filled for improved cooling.

And the lead problem? Still there, say owners. The O-235 accumulated lead deposits in every nook and cranny and lead fouling of plugs became such a problem that Champion developed a special extended-electrode spark plug for this engine, the REM37BY. Mechanics say even with careful leaning, the plugs must be removed and cleaned as often as every 25 hours. In Service Instruction 1418, Lycoming explains a procedure whereby cylinders can be blast-cleaned with walnut shells without removal for top-end overhaul. Prior to this, operators found that early tops were needed due to lead fouling.

One positive aspect of the Lycoming engine is its TBO—a whopping 2400 hours. If you can keep the thing from choking with lead, it may actually reach that impressive limit. Some owners use TCP additive to help control lead.

Unique to the mass-market trainer, Cessna offered two additional versions of both the 150 and 152—the Aerobat and a seaplane conversion, which appeared in 1968. There are still a few of these models running around, some even used on the water. The seaplane was, by most accounts, a decent little water taxi, although no one would mistake it for a Beaver. It couldn’t haul much and with limited power, it took a while to unstick from the water.

The Aerobat version—which first appeared in the A150 (K model) in 1970—made a much bigger splash, although not in the water. In those days, aerobatic training was all but impossible so when the Cessna Aerobats, with their flashy checkerboard paint, showed up on the rental line, many renters responded enthusiastically. Some 5 percent of the 150/152 fleet is acrobatically capable, after a fashion. The Aerobat commanded a price premium when new—about $1500 to $2000.

These days, any 150 or 152 Aerboat will still be premium priced. When we were shopping last year, we couldn’t touch a decent one for under $40,000. The latest Aircraft Bluebook (Winter 2022) pegs the retail price meter at nearly $60,000. Worth it? For some looking to get their aerobatic feet wet.

We’re not talking Extra 300 or even Pitts-type performance, of course. Aerobatic purists sniff at the Aerobat because it has control wheels, not a stick. Any maneuvers that require climbing back to altitude will require a plodding climb to get back in the perch. Still, the Aerobat was and is an affordable gateway into the world of aerobatics and at the very least, upset training—something we strongly recommend.

FLYING CHARACTERISTICS

No, these airplanes are far from speed demons and they don’t handle like flying sports cars. Still, the 150/152 has better than credible performance and handling traits. Interestingly, some flight schools report that although many students take intro rides in a modern LSA with the latest and greatest glass avionics, they transition to a 152 or 172.

Why? Probably because the 152’s higher weight gives it a somewhat stabler feel than a hyper-light LSA and price-wise, 152s remain competitive to buy and operate, so the hourly rental is less. Furthermore, some instructors say it’s easier to solo a student in a 150/152 because LSAs tend to be twitchy, especially in pitch.

But the Katana cruises faster than the 152 and uses more fuel. It’s a better climber than the Katana A1, with its 80-HP Rotax engine, but the C1 Katana, with its Continental IO-240, outdoes both the 152 and the A1 Katana, not to mention many LSAs.

Top speed for the 152 is given as 109 knots, same as the Tomahawk and two knots faster than the plodding Skipper. In the real world, owners say they go slower. Much slower. The airplane seems happiest at 90 to 95 knots, a realistic speed based on the ones we fly.

Handling is what it is, which is predictable, with relatively light control forces and no nasty stall habits. The Cessna 150/152’s slow flight characteristics are so utterly benign that they nearly qualify as STOL airplanes. The large flaps—even when limited to 30 degrees—are quite effective, although they do generate quite a nose-down trim moment. This is easily handled, although the control forces escalate somewhat. Students have to be taught to watch for abrupt noseups when applying full power for a go-around, training that prepares them nicely to transition into the Cessna 172, which has the same characteristic.

Landing a 150/152 is easy enough to teach and learn, to a point. And that point is often exceeded, since runway prangs are the most common type of accident suffered by the 150/152 series and other trainers, for that matter. The model is an excellent crosswind trainer, since it has an effective rudder.

The airplane is comfortable with an approach speed of 60 knots or slower, but it will easily tolerate higher speeds, because those draggy flaps bleed off excess airspeed in a heartbeat. Land it fast and it will bounce. That’s why any prebuy should include a specific check of the logs (and the airplane) for landing damage. Look for evidence of nosewheel work or firewall damage—especially when serving duty on training lines. Repairs done (and documented) right aren’t a big deal.

We think the 152’s runway performance is good, especially if the airplane is light. It’s not as good when heavy on a hot day. With a portly CFI and student aboard, more than a few 152s have trimmed the trees off the end of runways.

Speaking of payload, the 150/152 essentially carries what other popular trainers do. At 528 pounds useful, it carries a bit more than the Katana but a bit less than the Skipper and Tomahawk. Before the model got fat, some E/F/G 150s topped 600 pounds in load-carrying capability.

Where the 152 shines, however, is on load flexibility. With a fuel capacity of 38 gallons for the long-range tanks, it has better range with a single pilot than either the Tomahawk or the Skipper. Does this really matter? Maybe. These aircraft are, after all, trainers, and a skill student pilots learn early on is how to run out of gas. Plus, with decent range, they can make for affordable travelers if you have lots of time.

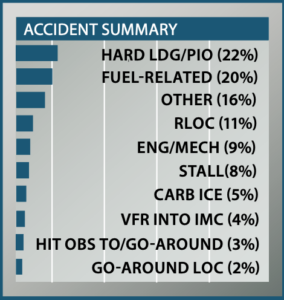

Our review of the 100 most recent accidents involving Cessna 150s and 152s turned up things we expected—landing accidents in probably the most popular trainer in history—and things we didn’t—several fuel-related accidents in an airplane with the most simple to use fuel system possible.

We expected to see that students rolled the two-seat Cessnas into aluminum balls on landing with alacrity, but we didn’t. We think that the relatively low rate is because of the excellent handling built into the marque.

Landing-related accidents—runway loss of control (RLOC), hard and bounced landings, pilot-induced oscillation (PIO) events, and unsuccessful go-arounds—made up 36 percent of the total accidents. Yet, that’s lower than such airplanes as the Cessna 172 (44 percent) and the Piper Archer (39 percent) that are commonly used as trainers. Our hypothesis is that the four-place trainers are flown solo near the forward center of gravity limit, making flare and landing slightly more challenging than the 150/152, which is generally flown solo near the center of the CG range.

The low RLOC rate (11 percent) is consistent with our experience in the airplanes and their quality of low-speed handling and capability to deal with crosswinds. Three of the 11 RLOC events were in tailwheel-converted airplanes—so the real RLOC rate is 8 percent.

The great majority of the hard/bounced landing accidents involved students and nearly every one also degenerated into PIO and breaking the nosegear as the oscillations grew dramatic. We think that is a reflection of the need for better flight instruction focused on how to recover from bounced landings—not an issue specific to the 150/152, as we observed the same phenomena in all of the other trainers.

Only one overshot landing accident was reported—an unusually low number. That reflects, in our opinion, the low landing speed and effectiveness of the Fowler flaps on the 150/152. Plus the accident seemed to have taken some effort on the part of the pilot. He decided to land with a 20-knot tailwind on a 2500-foot grass runway, although he was landing uphill. He approached with extra airspeed, floated, bounced and then added power to cushion his touchdown. Shortly after that he discovered that he couldn’t stop on the remaining runway.

We were surprised by the number of fuel-related accidents in an aircraft with an on/off fuel system. Historically, as the number of tank selection options for a pilot increases, the number of fuel-related accidents goes up as pilots run a tank dry and don’t manage to switch into a tank containing fuel before returning to the planet.

Almost all of the accidents involved fuel exhaustion (three were due to water in the system that wasn’t drained). We saw none involving solo students. Most involved departing with partial fuel—the rest, in our opinion, involved unreasonable optimism regarding full-fuel endurance. Between the lines, we noted that at least some of the pilots were running the mixture full rich despite the POH/Owner’s Manual direction to lean the mixture in cruise, no matter what the altitude.

CABIN, ERGONOMICS

Cabin comfort is not much of a consideration in two-place trainers, and there isn’t much luxury built into a 150 or 152. Think utility. Flight lessons are short and there’s no point in pretending there’s enough room in the airplane for plush seats. The 150/152 is so narrow that even pilots of moderate size will bump shoulders. Two big guys will be miserable. Although the seat height is quite low, the legroom is excellent for stretching out.

In 1979, thicker seat padding became standard, but it helps only a little. Many owners have had the seats repadded (a worthy upgrade, we think) or carry a pillow or two to make them more tolerable. Noise level is quite high, due to the proximity of the cabin to the engine compartment, but the advent of noise-canceling headsets and intercoms has rendered this moot.

Ventilation in the 150/152 is via the standard Cessna pull vents in the wing roots, plus in most models the windows open for taxi and can also be opened in flight. During the winter, this can be a mixed blessing and some operators tape off the root vents to reduce drafts. If the heater works, it will get the job done. There isn’t a lot of cabin to heat.

WRENCHING, SUPPORT AND MODS

In general, these are simple airframes that don’t require much maintenance. However, any that have been used extensively as trainers—as most have—should be inspected carefully for hard landing damage, especially in the nosegear/firewall bulkhead area. “Unless the guy that you bought the airplane from spent a bunch of time and money fixing up that 20-year-old airplane and fixing/replacing/repairing a lot of things, you can expect that you will be that person if you are conscientious about your maintenance,” one owner told us

The 150/152 series has what we would call an average list of ADs, none of which are particularly onerous or expensive. The major safety-related item is the seat track AD, which prevents the seat from unlocking and sliding rearward. Most aircraft should have had this done long ago.

Owners report that annuals are thrifty—in the $800 to $1200 range, depending on parts needed.

The Cessna 150-152 Club has a monthly newsletter that’s an excellent clearing house for information, parts, mods, maintenance and service tips. It has a tremendous amount of technical and operating information on the airplanes, and we think anyone considering a purchase should join.

It also has a delightful annual fly-in near the time of AirVenture at Clinton, Iowa, not too far from Oshkosh. It has technical presentations, a number of competitions such as spot landing and extensive opportunities to socialize with other owners, and the organizers make a concerted effort to keep the cost down. We’ve observed club members go to great lengths to help out other 150/152 owners. Contact the club at 541-772-8601 or www.cessna150-152club.com. Also, for a detailed book on flying and operating Cessna 150s, contact Arman Publishing at www.Cessna150book.com.

As for mods, there are plenty, and the type clubs are a good resource. Some standouts: Horton Inc. (www.stackdoor.com, 800-835-2051) sells STOL kits for the 150/152. Met-Co-Aire sells wingtips for the 150 series; reach them at 714-870-4610 or www.metcoaire.com. Griggs Aircraft in Pennsylvania now owns the STC for the O&N extended fuel tanks for the 150/152. Visit www.griggsaircraft.com

Some 152s have the Air Mods engine conversion that includes a new prop that boosts climb and takeoff performance by allowing the Lycoming O-235 to spin up to 2800 RPM. It also has a higher compression ratio so supposedly, this decreases lead fouling. We couldn’t find an active contact at press time.

OWNER COMMENTS

I highly recommend the Cessna 152 Aerobat if you can find one. They’re great for positive-G maneuvers and one of the more affordable aerobatic machines out there. I learned to fly in a 152, and always thought they were fun, but aerobatic capability makes them a blast!

These are old airplanes, and many were trainers, so for “bargain buys,” you can expect to spend as much or more than the purchase price on upgrades and repairs. Since purchase, I’ve had the engine overhauled, skylights replaced, exterior plastic replaced, cowl fasteners upgraded, radio upgraded and the electrical system rewired. A paint job and new interior are next.

Insurance and operating costs are low, and when not doing aerobatics it works great for $100 hamburger runs, turf fields and fly and hike adventures. If you aren’t in a hurry, it’s fine for VFR cross-country trips, and you can always throw in a few rolls if you get restless and want to spice up the flight.

Insurance for my 1972 A150L is $581 for a $45,000 hull value, and fuel burn is about 5 GPH.

Dimitri Bevc – via email

We own a 1976 Cessna 150M. When we bought it in 2013 it had just over 4000 hours on the airframe and a run-out engine. We did an extensive annual on it, including overhauling two of the Continental cylinders, in an attempt to get a little more time out of the engine. It was a bad idea. Within a year the engine starting making metal, so we tore it down and did a field overhaul. This is the original engine that came from the factory with this airframe, and as such, is now the second overhaul of this engine. We tried to do it right.

We installed Millennium cylinders and in addition to the normal stuff done to an engine during an overhaul, we overhauled all of the accessories and replaced all of the baffle system with an Air Forms replacement baffle kit. All in all we spent a little over $10,000. I am the A&P/IA of our little partnership, and my labor was donated, so the $10,000 price does not include any allowance for my time to remove the engine, disassemble and reassemble it and reinstall it. This, on an airplane that we bought for $10,500.

We saw a very noticeable increase in power by replacing the cylinders with Superior Millenniums. Two years later we decided to paint the airplane at a well-respected paint shop in Salinas, California. Just before taking it to the paint shop, we replaced all of the windows. New windows and new paint made the airplane look like new. Paint was $11,300. We now had north of $30,000 invested, and have four partners in the plane, so projects like this were doable. Two of the partners (me included) bought into the plane so that family members could learn to fly in it. My daughter soloed in it in August of 2018. Another partner’s son got his license in the airplane last summer. The reasons for buying the plane are working as planned.

We experienced engine surging on a couple of different occasions, and it appeared to be due to fuel venting. I tried a number of things to make sure it didn’t happen again, including having the carburetor reinspected, fire sleeving the fuel supply line from the strainer to the carburetor, replacing the fuel vent line and replacing the fuel caps. When it happened yet again I replaced the vent valve in the left wing tank, and since then have not experienced another engine surging issue. I am hopeful that we have put that bit of nastiness behind us.

We went all out for our ADS-B solution and installed the Garmin GNX 375. This is a really nice solution as it is a new transponder, ADS-B In and Out, a moving map GPS and LPV approach capability. We have over $40,000 invested now. It is insured for $35,000, and $1 million worth of liability insurance costs us $797 per year, with the least experienced pilot a student. The only thing we wish for is the pre-select flaps that are on the 1977 models.

David LeTourneau – via email

In the past year I’ve gotten to enjoy my 1982 Cessna 152 quite a bit. It is relaxing to watch the landscape go by at just under 100 KIAS. Passengers seem to enjoy it and think we’re going plenty fast. I know what to expect from the plane’s performance and handling and fuel usage. At first I was overly concerned about the useful load. Extended-range tanks and new (1/4-inch-thick) Plexiglas and paint will add weight.

I am planning on a long-term relationship with the plane and after much thought decided to add a few embellishments, including vortex generators (rather than a Sportsman-type leading edge STOL modification because of further weight penalty) to improve slow-flight characteristics (claiming 3- to 6-knot decrease in stall speed), wingtip LED lights (it seems that I’m always getting back home after dark) and a JPI 900 engine monitor with digital fuel senders. This will also allow for a new powder-coated panel, while decluttering it and improving night instrument lighting.

Finally, while I feel I did my due diligence before purchasing the airplane, I would have been more involved with the prebuy inspection. A good friend referred me to an A&P/IA prebuy evaluation, and I pretty much left it to him to tell me what I needed to know about this plane. There were only a few small details that needed attention, which we addressed. However, within several hours of flying while wheel pants were still on I noticed a well-worn bald spot on one of the tires, so I had all three tires changed. My first annual inspection had more items to be addressed than I would have anticipated, including changing a corroded metal fuel line, replacement of a wing tank sump drain, a leaking fuel primer and exhaust slip joint corrosion. Additionally on a cross-country flight on a nice VFR day, the alternator failed just prior to landing at the destination. My passenger noticed the red low-voltage annunciator shortly after I did. It failed slowly enough that I was able to start the engine, depart and make it within 20 miles of my home airport before the voltage dropped to a single digit. I shut down everything after notifying ATC of the situation. I had enough battery power left to lower the flaps and I used a handheld radio to talk through an uneventful landing. Of course, that necessitated replacing the alternator and the 24-volt battery.

I understand that there will be a composite propeller option at some point, so I may be looking into that as well.

When I was a teenager flying my family’s 1941 Piper Cub J5, I used to fantasize about owning a Cessna 150. I had a 150 brochure and would marvel at the modern panel, avionics and “spacious” cargo area. Later, as a young man I purchased my first Cessna 150 and my wife and I went on many nice trips with it. Then wanting an instrument rating, I moved up to a Cessna 172 and then a Mooney M20F to really use my instrument rating with my family. After many years I finally sold the Mooney and was looking for a step-down, two-seater for my retirement years. I considered returning to taildraggers, but the lure of owning a 150 was just too strong, so I bought my second 150 and have had no regrets over the past nine years of ownership.

It met my needs as most of my flying was solo and regional. I did not hesitate, however, to take the plane on day-long, two- or three-leg cross-country flights. Due to its short range and light wing loading, the 150 is not what you would consider to be an IFR aircraft. Still, I maintained my IFR currency in my plane and practiced approaches with a safety pilot or did approaches on MVFR days. On long cross-country trips I usually filed IFR to get “on top” so I didn’t have to bang around underneath a cloud deck. Useful load is limited. If you bring a passenger, don’t plan to pack much.

I flight planned for 95 knots at 5.5 GPH. That will give a three -hour endurance, with a one-hour reserve. Having a fuel flow meter installed was a nice addition. I avoided installing an expensive IFR GPS as I doubted I could ever recoup the cost when I sold the plane.

It was listed for $42,500 and I began getting a huge response immediately, so I raised it to $43,500 the next day. The day after that I had a signed purchase agreement for $44,000.

Being a seller’s market, all of the buyers I was talking to were all willing to make concessions including forgoing a prebuy evaluation and accepting the last annual and latest log- book entries. They would pay for the escrow service costs in full (around $450), plus pay the full asking price or higher for the plane.

Two days after listing the ad, I had four solid buyers pestering me to purchase my plane. I found that I could be choosy about who purchased the airplane. If I thought that the plane wouldn’t be taken care of we’ll (like not stored in a hangar), they moved lower on my list.

I was told that flight schools want to purchase these 150s, but I did not get one call from a flight school. They were all private or commercial pilots (two airline pilots, including the one I sold it to). I had an interested buyer who said he was a student pilot, but I don’t believe he was even that. He wanted to buy the airplane and eventually fly the plane back to the Boston area on his own without a pilot’s license.

In the end I had a purchase agreement for $44,000 from the first man I spoke with no more than a couple of hours after posting the ad for $42,500. The next day he voluntarily raised his offer to $44,000, which helped with the deal as I was having seller’s regret that I listed it too low of a selling price. I’m sure I could have gotten maybe $46,000 or more for the plane. Who knows?

Robert Russell -via email