The Cessna 337 Skymaster is arguably the most commercially successful so-called push-pull attempt, at least in terms of numbers built. And although the 337 Skymaster isn’t the most popular twin ever marketed, it’s done just fine for itself and has achieved its primary goal: eliminating asymmetric thrust and simplifying the pilot’s workload in the event of an engine out. Unfortunately, as you’ll see in our accident scan on page 30, some Skymaster pilots find plenty of other ways to NTSB fame.

Still, the idea of the push-pull twin makes such fundamental sense that it has been applied to aircraft designs in one form or another for nearly 100 years and in literally dozens of models you’ve never even heard of. Remember back in 2005 when Adam Aircraft tried the idea again with the A500 push-pull piston twin? We do, and like many before it, it failed more by market reality than by a fundamental flaw in the idea. We really wanted that one to work.

If the push-pull concept was seamless, the execution of it by Cessna was a little less so. The Skymaster acquired a reputation as a bit of a maintenance hog and although its performance is respectable, other twins do just as well, if not better, on less fuel and on fewer dollars spent on wrenching. Like most used twins on the market today, some Skymasters are a bargain, but others are premium priced. When avgas prices started to climb, market values of twins started downward and today, you can find a reasonably well-equipped Skymaster for under $100,000. Airframe values seem to have stabilized since we first examined them several years ago, which is more than we can say for other piston twins.

Not Really Simpler

When Cessna began to develop the Skymaster in the mid-1960s, the accident history was horrid for twins. Part of that was due to training. The doctrine in those days was to actually surprise the pilot with a real engine shutdown to simulate losing one. In the hairy-chested thinking of the day, instructors would even do this on takeoff. As a result, loss-of-control accidents due to VMC rollovers were, if not common, more prevalent then they are today.

In an engine-out situation, conventional piston twins generally need to be handled with kid gloves lest the airplane get too slow and roll over on its back. So Cessna approached this problem just as other designers had going back to the Caproni Ca.1 of 1914: They aligned the two engines with the airframe centerline, offering pilots the safety of a second engine without the penalty of adverse handling. If one quits, identify it, feather it and don’t worry about the dead-foot, dead-engine drill. The FAA even granted the 337 its own class rating, limiting pilots to centerline-thrust twins only. It was much easier-and probably safer-to earn a multi-engine rating in a Skymaster than in a conventional twin.

Part of Cessna’s plan worked, since there’s little question the Skymaster is easier to fly on a single engine than a conventional twin. But, since the VMC rollover accident doesn’t happen that often in the real world because training doctrine moved to zero thrust instead of an actual engine shutdown, the airplane’s overall accident record isn’t that much better than conventional twins.

A pilot looking to improve redundancy by stepping up from a single to a twin certainly will achieve it with a Skymaster. But in the bargain of gaining redundancy, pilots can be forced to accept a platform with more cabin noise, a set of operating peculiarities all its own and tightly packaged systems presenting more of a challenge to maintenance personnel than if each engine resided on its own wing. All of this might argue in favor of a single-engine airplane or even a conventional twin. Then again, if you fly over the Great Lakes at night, maybe not.

Model History

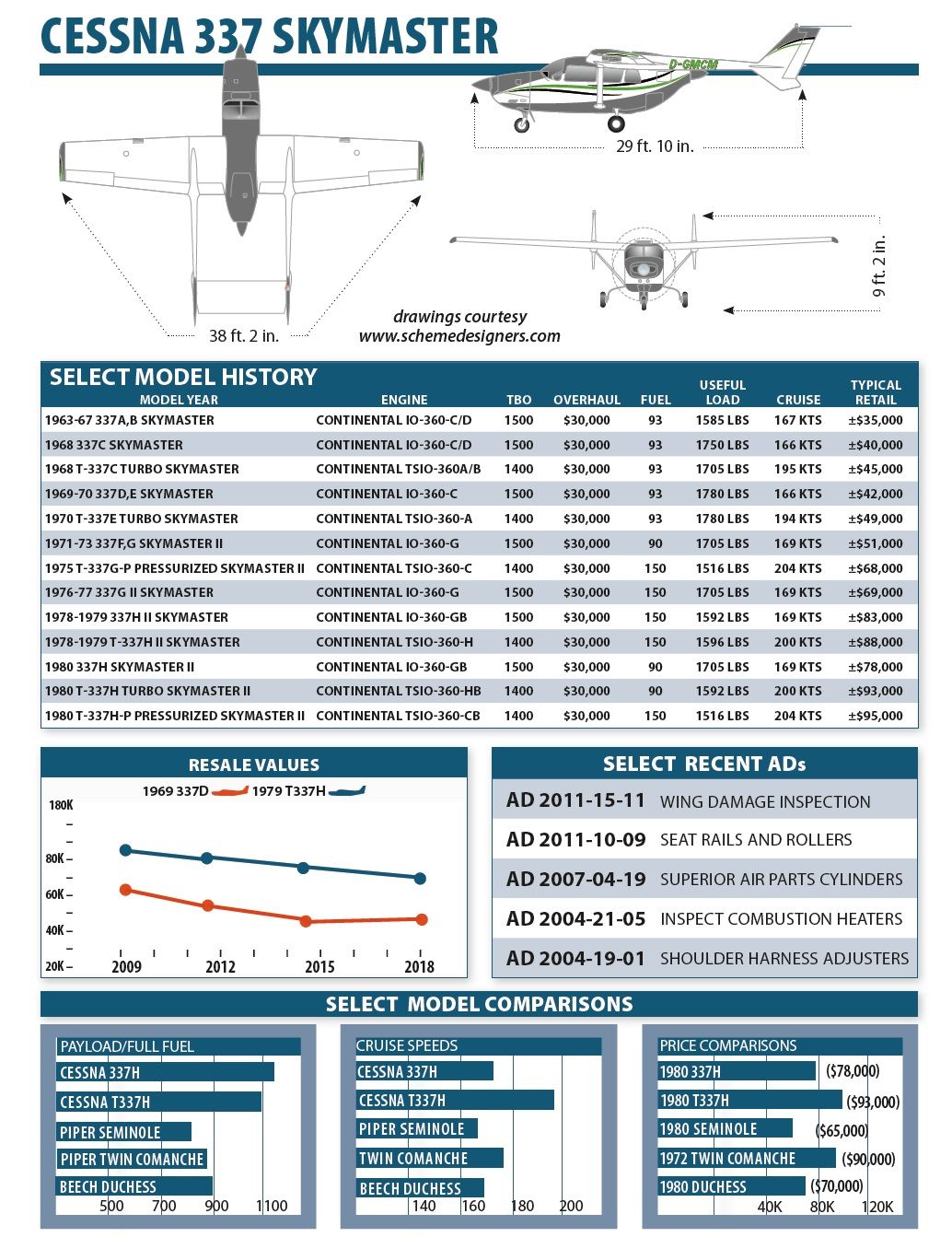

The 337 Skymaster’s front/rear engine layout and high wing started out as the fixed-gear Model 336 in 1964, powered by Continental IO-360-A engines of 195 HP apiece. Widely acknowledged as a slug, Cessna sold only 195 336s in one year of production; around 80 remain on the FAA’s registry today. In 1965, the company folded the gear and upgraded powerplants to a pair of Continental IO-360-Cs pumping out 210 HP, resulting in the 337 Skymaster. Cessna sold 239 copies that year. (Not really learning from its 336 experience, Cessna flew a cantilever-winged, lower-powered version, the 327, in late 1967, but it proved too slow and the project was dropped the next year.)

To make the original 336 a retractable, Cessna borrowed the complex and occasionally troublesome hydraulic landing gear system from the 210. In 1973, it was upgraded to a simpler and more reliable electrohydraulic system. While less complex and easier to maintain, the system still isn’t as robust as, say, a Baron’s or Seneca’s.

Early models also came with multiple fuel tanks, a system that proved problematic in the field. It was replaced in 1973 by a superior, less complicated system. A turbo version-the T-337B, powered by 210-HP TSIO-360-A or -B engines from Continental-appeared in 1967, but was dropped in 1972 with the addition to the Skymaster line of the almost-revolutionary pressurized 337 version, the T-337G-P, powered by TSIO-360-C engines up-rated to 225 HP.

Major tweaks in the airplane’s history were few, but there were many designation changes. Beginning in 1970, some inspection panels were added-making maintenance easier-and the airframe was lightened a bit, increasing useful load. The interior arrangement also changed through the years, with various combinations of seat mounting.

As is common with any aircraft, the non-pressurized 337’s gross weight crept up during its years in production. Early models started at around 4200 pounds; late ones weighed 4630 pounds, with max landing weight limited to 4400 pounds. Meanwhile, the P-337, with its 30 extra horsepower, had a takeoff weight of 4700 pounds and max landing weight of 4465 pounds.

Piston-twin prices are still a bit soft, and the 337 is no exception. On the upside, most of the depreciation has been squeezed out of these airframes. The downside? Cessna 337s can’t be counted on to increase much in value. But a Skymaster is a lot of airplane for the money. Besides current fuel prices and future uncertainties, other factors depressing prices are that the 337 has a reputation for being a maintenance hog-one that’s not entirely deserved-and they aren’t all that fast as like-powered twins go.

Buyers should be aware, however, that buying a cheap twin is not the same as operating a twin cheaply. A hangar queen will eat through a bunch of money if it needs remedial work and, in any case, you’ll need to find a shop familiar with the breed to do the prebuy and maintain the airplane going forward. The Skymaster doesn’t perform much better than a Cessna 210, and it has two of everything to maintain and replace, driving up ownership costs.

Performance, Handling

Skymasters aren’t speed demons, although the turbocharged models do respectably we’ll for pilots willing to take them into the teens. Owners of normally aspirated models can plan on between 155 and 165 knots true, depending on altitude and how much fuel they want to burn. The turbocharged and pressurized models will push 190 to 200 knots at 20,000 feet, their maximum certified altitude. At middle altitudes, 170 to 180 knots is typical for the turbo models, which isn’t all that bad.

Since Skymasters have relatively small displacement six-cylinder engines, fuel burn tends to be reasonable, ranging from 15 GPH to 22 GPH total, with 19 to 20 GPH typical for a 150- to 160-knot cruise. For comparison, a Twin Comanche will do about the same speed on 100 fewer horsepower and a lot less gas. Efficiency isn’t a Skymaster hallmark, except when compared to larger, faster twins.

All-engine rate of climb ranges from a modest 1300 FPM in the old 336 to a lethargic 940 FPM with the last 337H models. We’re unaware of any other twin-engine airplane with a book rate of climb below 1000 FPM; even the old 150-HP Apache had a book climb of 1250 FPM with both engines running. On the other hand, lose an engine in a 210 and there’s no rate of climb, only a rate of descent. In a 337, you should at least be able to eke out 200-300 FPM.

Like many Cessnas, runway performance is good. Landing-configuration stall speeds range from 55 to 62 knots, depending on the gross weight of the particular model-about 10 knots below conventional twins like the 310.

As a result, a Skymaster will get off the ground in less than 1000 feet at gross weight-a feat very few other twins can manage. Barrier performance is not quite as good, however; the leisurely climb rate brings the Skymaster’s 50-foot takeoff figures down to the middle of the light-twin pack.

What’s surprising is the difference between the front and rear engines. Climb on the front engine only is about 50 FPM less than on the rear, but not necessarily for all versions of the Skymaster. Reader Robert Prader told us his research reveals that later models have better front-engine performance. “It is true that front and rear engine single-engine climb rates are significantly different for all pre-1973 Skymaster models; however, the front and rear single-engine climb rates are not significantly different for the pressurized models and the 1978 and later turbo models,” he said. “If you consult the POH for any pressurized model, you will find that a single-engine climb rate of 375 FPM is listed for a standard day at sea level at gross weight, with no mention of which engine is out. If you consult the POH for the 1980 non-pressurized turbo model, you will find it specifies a climb rate of 335 FPM for the same conditions, again with no mention of which engine is out.”

While leaving the gear down produces a climb penalty of a bit over 100 FPM, raising it carries a temporary 240 FPM hit. (Praeder told us this is about average for most twins and probably for single-engine retracts as well.) This is because Cessna’s complicated gear door arrangement adds drag while the gear is in transit. In an after-takeoff engine-out situation, it may be better to leave the gear down, just as it is recommended in some singles to leave it down until obstacles are cleared.

pressurized P337H. These are premium

priced.

The noteworthy aspect of the Skymaster’s handling-indeed, the whole reason for the airplane’s existence-shows up when an engine fails. Instead of the normal yaw-roll-stall-spin scenario too often following engine failure in “conventional” twins, the Skymaster continues to fly straight ahead. An unprepared or rusty pilot can take his time and concentrate on the task of identifying and feathering the prop on the failed engine, without worrying about losing control.

Payload, Range

A Cessna press release from the 1970s describes the Skymaster as “a full six-place airplane with nearly a ton of useful load.”

Good luck with that. At best, the two rear seats can accommodate youngsters. And that press release conveniently forgot when the fifth and sixth seats are installed, there’s no baggage space, nor is there a baggage door. Consider the Skymaster a roomy four-placer.

Real-world useful loads run around 1500 pounds-not bad at all, and several hundred pounds more than a Twin Comanche. Standard fuel is 93 gallons, which should leave more than 900 pounds available for payload; plenty for four passengers and their bags. Standard fuel is just adequate, however-unless you throttle back-providing a bit more than three hours with IFR reserves at fast cruise.

Pre-1973 airplanes with long-range tanks had a four-tank fuel system; later ones came with a two-tank system. The long-range tanks-150 gallons in 1975 to 1980 models, 131 gallons in earlier models-solve endurance limitations nicely, at the expense of payload, of course. One owner told us that with long-range tanks full, he has seven-plus hours at 150 knots with 650 pounds of payload (three people and bags). Not a bad compromise.

Oddly, the P-337 is allowed only five people; it was certified under different rules requiring an emergency exit in a six-seat airplane. Rather than put in the exit, Cessna simply limited the seating to five. Early P models had a middle seat hinged up and to the side to get at the back row, but these seats didn’t slide fore and aft. Access to the rear seats in other Skymasters requires an awkward scramble over the center row.

The Skymaster’s visibility is excellent-about as good as it gets in any light airplane, single or twin. The view down is unlimited, of course, and the wing’s leading edge is back far enough that it doesn’t block upward vision, either, as with most Cessna singles. Good visibility is not only a safety feature; it adds to the feeling of roominess in the cockpit.

The Skymaster is also quite noisy, since the passengers are sandwiched between the engines. Also, sympathetic vibration can be a problem, particularly without prop synchronizers. Conventional twins are quieter by far.

Maintenance Mods

The Skymaster was the most complex aircraft ever engineered and manufactured by Cessna’s Pawnee Division, which otherwise built only Cessna singles. Evidence suggests the division simply wasn’t up to the task, particularly in the 1975-1980 period when production was growing rapidly and Cessna was plagued by an epidemic of design, engineering and production problems.

For example, the pressurized Skymaster was initially such a disaster that the first year’s production was recalled to the factory for complete remanufacture and modification. Distinct from other twins, Cessna had to pack everything into the fuselage, not having the luxury of sticking systems out in the wings or into the nose. As a result, access is difficult and it is those systems where most maintenance problems will be found.

The basic airframe is stout, with a rugged strut-braced wing. There are remarkably few ADs on the airplane. And remember that the military version of the Skymaster did plenty of rough duty in Vietnam, often flying home with bullet holes or worse.

Still, a potential Skymaster nightmare is runaway maintenance costs, particularly in the turbo and pressurized models, so the prudent purchaser will closely examine logbooks and service records of any aircraft under consideration.

The Riley Rocket was a popular Skymaster mod and included upgrades to 310-HP TSIO-520 engines, intercoolers, three-blade props and air conditioning. Rockets come on the market now and again, at a premium price over stock models.

Ohio-based Aircraft Sales’ Pristine Airplanes modification (www.pristineairplanes.com) offers the Rocket II full refurb for the Skymaster, while adding intercoolers to P337 models, plus new avionics, paint and interior on all models. Including the aircraft, a fully refurbed Rocket II could top $600,000, but like all of the other refurbished aircraft the company pumps out the end result is a like-new aircraft, following almost six months of intense rework.

Other 337 mods include vortex generators from Micro Aerodynamics (www.microaero.com) and intercoolers from American Aviation (www.americanaviationinc.com). Both Horton (www.hortonstackdoor.com/stolcraft_description.htm) and Sierra Industries (www.sijet.com) apparently still offer STOL kits and other aerodynamic mods. A wing spoiler kit is available from PowerPac Spoilers (www.powerpacspoilers.com).

Aviation Enterprises (www.cessnaskymaster.com) offers a wide range of major modifications for Skymasters, ranging from air conditioning, airstair doors, extended wingtips, IO-550 engine conversions-for one or both engines-long-range fuel and MT propellers. The company also can provide various parts, including cargo pods. Similarly, RT Aerospace (www.rtaerospace.com) offers several items of interest to the Skymaster owner, including a convertible rear seat for the baggage area.

Cessnas seem generally blessed with good owner organizations, perhaps because the company abandoned the piston market in 1986 and stayed out of it until 1997. The clubs and groups have proven to be as good as it gets when it comes to support.

Every Cessna owner should join the Cessna Pilots Association (www.cessna.org). The organization offers the usual benefits, including an insurance program, monthly newsletter and fly-ins, and has a wealth of Skymaster-specific information. We found a useful if unofficial Skymaster website for the Cessna Skymaster-SOAP, for the Skymaster Owners And Pilots (www.337skymaster.com).

Cessna 337 Mishaps: Pilots

Our review of the 100 most recent accidents involving airplanes in the Cessna 337 series produced results that were good, bad and, frankly, just plain strange.

We’ll start with the good news: There were only two runway loss of control (LOC) accidents involving 337s-a very low rate and, in our opinion, powerful evidence of good ground-handling characteristics of the marque.

On the bad news side, we were surprised by the number of fuel-related accidents-15. That is nearly twice the rate we’ve observed for the tip-tank Cessna twins-300- and 400-series-which have a reputation for being endowed with a complex fuel system.

The fuel-related accidents were split almost evenly between pilots who mismanaged the fuel aboard-running a tank or tanks dry and not causing fuel to flow from a tank containing it to the engine(s)-and simply not putting enough fuel in the airplane for the intended flight. However, where things started to turn strange to us was that so many pilots simply didn’t bother to check to see if they had any fuel in the airplane at all (or were too cheap to buy any) and had the engines quit right after takeoff. One put fuel in only one wing and others only in the aux tanks and then selected the nearly empty tanks.

In proving that the late gonzo journalist Hunter Thompson was right when he said, “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro,” one pilot decided to ferry his 337 for maintenance after the interior had been stripped out-including the fuel selector handles. You got it, he ran tanks dry and couldn’t turn the valves to change tanks.

We’ve flown Skymasters off and on for nearly 40 years, have done single-engine work and observed that they go straight ahead following an engine stoppage and will hold altitude and usually climb if the POH procedures for engine failure are followed. That was confirmed by a pilot who was scud running beneath an overcast, in flat light off the coast of Alaska on a winter day. He hit a pressure ridge in the ice, wrapping the front prop around the cowling and stopping its rotation. He was able to continue to his destination.

Six pilots lost an engine after takeoff and did nothing to clean up the airplane. Not surprisingly, they were unable to climb. Nearly all of them then stalled the airplane and lost control. A pilot who lost an engine in cruise and landed in a field after not feathering the prop was unable to describe the engine failure procedure for the airplane.

At least five pilots unsuccessfully tried a single-engine takeoff-some after arguing with other pilots who tried to talk them out of it and one with passengers. One of the airplanes had not had an annual in 10 years.

There were five fatal accidents and one non-fatal in which the pilots had incapacitated themselves with drugs or alcohol.

The rate of what we consider stupid pilot tricks was so high in the 337 we can’t help but wonder about why an airplane designed to be safe may attract more than its fair share of pilots who don’t seem to give a fig about safe operations. On that note we’ll close with the 337 pilot who was practicing his IFR skills at night, without a safety pilot, and flew into the side of a mountain.

Owner Feedback

I’m the owner of my second Cessna 337, a 1977 normally aspirated 337G Skymaster II. The 1976 and newer models incorporate all the design upgrades done throughout the 337 model run, and a particularly nice upgrade, the 150-gallon long-rang tanks. This is an on/off cross-feed fuel system, which means there are no tanks to switch, just front and rear. Four metal tanks in each wing utilize the wing dihedral sloped to drain 100 percent to the inboard wing root tank, with only 1.2 gallons of unusable fuel on each side. There’s also heavy-duty landing gear, larger wheels and heavy-duty double-puck Clevelands with semi-metallic brake pads, another real nice option that came standard on 1977 Skymaster II models.

I prefer the “aspros,” normally aspirated Continental IO-360 G engines, which will go to TBO and beyond, but their weakness (being a lightweight Continental engine design) is they don’t tolerate the heat distress of turbocharging, and particularly the always-on heat distress of turbocharging plus bleed-air pressurization. My engines have 1800 hours (Continental remans) and burn one quart of oil every five hours. Plan on roughly $60,000 for factory reman engines and props, and more for turbocharging.

As for maintenance, as an owner/mechanic I can say plan on a lot. As a rule of thumb, budget as much as you would for a last-minute first-class airline ticket for everywhere you go in a 337. I hate to say what’s been said plenty of times: There are more buyers who can afford the 337’s purchase price that can actually afford to properly maintain it. If a purchaser is financially well-off enough to simply toss the keys to one of the several well-known and well-respected 337 specialty shops to manage and perform routine maintenance, so much the better. Costs would not be a seen as show-stopper to keep such a unique and nice flying airplane in service.

Never forget that you are flying a 45-year-old legacy aircraft, which is the most complicated one ever built at Cessna’s Pawnee factory, and that includes the landing gear system. If you are not already a Cessna-knowledgeable A&P yourself, as I am, I would strongly suggest becoming one. Cessna factory technical and parts support is in general really excellent. Certain parts of course are no longer produced, but they’re available from vendors on the secondary and salvage markets.

The Cessna OEM fuel gages are functionally useless for planning maximum range, except for timed constant-power cross-country flying when starting with full tanks. Fortunately, Cessna’s fuel flow gauges are pretty accurate, and are helpful in that regard.

I suggest sourcing Cessna factory parts, service, wiring and maintenance manuals for the 337, in addition to the Continental engine manuals. I really feel this airplane can’t be owner-flown and maintained without them.

I have personal experience with Ron Lillie of Little Enterprises. He’s a longtime multiple 337 owner and pilot himself and the proprietor of a 337 specialty maintenance, service and sales organization in Salt Lake City, Utah, from whom I purchased my current 337G. Without hesitation I can recommend Lillie Enterprises as a highly knowledgeable, honest and ethical organization to do business with.

In my first 337B, I lost an engine while preoccupied by Houston Approach at a peak traffic time after a 30-minute flight from Austin, Texas, and forgetting to switch tanks after taking off and flying low and slow in a steep bank taking aerial photos of a construction site. Actually, it was such a non-event, I wasn’t immediately sure what had happened, but like in all light twins when something such as this happens, say your ahh shucks, and then try to figure out if the second engine is about to pack for the same reason as the first one. If so, you might have 10 seconds to do exactly the right thing. Head up and locked, true enough, but it might be a very different outcome in a conventional twin.

Inflight visibility outside the cockpit is as good as it gets. Like in a 500-series Aero Commander, you sit ahead of the wing’s leading edge. The only better flight visibility might be in a military O-2 model 337 with a full bubble side and overhead windows-the flight visibility is truly amazing. There’s also hardly ever the need to stand on a rudder during most conditions.

Cessna 337s generally handle with the familiar control forces of a heavy Cessna-think 210/206, except with lighter elevator forces, large long-span fowler flaps and with elevator trim tab and flaps interlocked to minimize attitude changes in landing configuration. There’s plenty enough rudder authority for wing-low slips for altitude control during approach. And it’s easy to land on the mains with the elevator authority to maintain a nose-high touchdown and rollout.

As for mods, gear door mods eliminate much of the complexity and maintenance burden of a seemingly endless number of squat switch adjustments and potential malfunctions causing mostly false positive indications of gear not down and locked. Seemingly the whole belly of the plane opens up at gear extension and retraction, so the gear door mod appears to be a pretty worthwhile, well-thought-out one.

When the gear doors open, they look like speedbrakes. They create a flat-plate area on the both the airplane nose and rear door pairs large enough to swallow up several beach balls, so it’s easy to understand why the landing gear system creates so much drag that the 337 won’t climb at gross weight after an engine failure during the takeoff roll and while the gear is in transit.

Robertson and Horton STOL kits, as we’ll as VGs, are available. Leading-edge cuff and stall fences aren’t too expensive to have installed and are generally agreed to aid low-speed controllability at the bottom of the airspeed/stall envelope, with no significant effect on cruise speed. The 337 comes over the fence a wee bit hot, so when flying heavy, any improvement to the low, slow and touchdown flight envelope would seem worthwhile.

As for insurance, driven by all the standard underwriting guidelines, hull valuation is a big factor. The same goes for pilot experience/time-in-type.

Pricing is all over the map and some new owners might find that getting insurance for a Skymaster might be cost prohibitive. Some might not even qualify without lots of additional training-not necessarily a bad thing.

–Terry Allen via email

I am on my second Skymaster; the first I had about five years and this current one we’ll over 10. The present one is a 1967 T337B. The biggest positive features of the Skymaster are, one, that it can carry just about anything I can stuff in it, and two, is that it has two engines. I live on the far north coast of California and there are serious mountains in three directions.

I have limited experience in Cessna 182 models, but the flying qualities seem similar.

I normally cruise in the mid teens and see a total fuel flow of 18 GPH there with 160 knots true airspeed. Insurance has cost me an average $2152 per year based on a hull value of $55,000. Parts and labor have averaged $8644 per year, with a high year around $15,000 and a low year just over $2000.

I have been a member of the Cessna Pilots Association since I got the first Skymaster and have benefited greatly from the organization. I also have been lucky to have a local IA who has plenty of experience with Skymasters.

–Steve Bowser via email