If you’ve ever practiced balked landings in a Skylane, you know how critical it is to keep the heavy nose down when transitioning out of the flare and into climb when configured with flaps, nose-up trim and full power. Our recent scan of 100 recent wrecks proved that Skylane pilots might benefit from more practice for these situations.

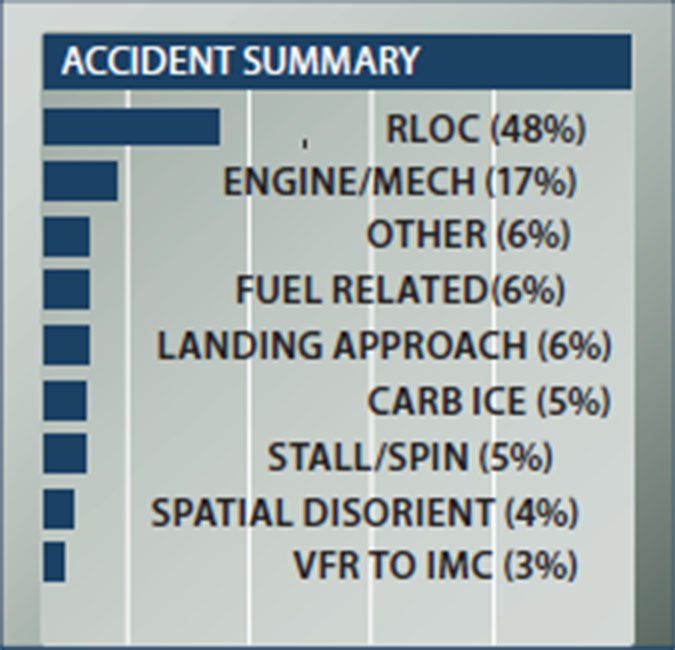

That’s because a whopping 47 percent of the 182 wrecks that made the NTSB reports fell into the RLOC, or runway loss of control, category. Our research became monotonous with an ugly pattern of landings gone bad, resulting in busted nosewheels, bent firewalls and twisted airframe structure. While some were benign prangs that resulted from not managing the flare, touchdown, crosswinds or simply not maintaining directional control, other landings were downright out of control, resulting in fatalities. These contributed to a total of 16 fatal crashes in our random research.

Sometimes practice didn’t help, as was the case with one pilot who told the NTSB he conducted several hundred takeoffs and landings at the accident airport over the past several years. He sadly lost a passenger on a botched go-around. Another 182 pilot botched the go-around so badly that he allowed the airplane to stall, followed by the left wing striking the edge of the runway and resultant inverted tumble into an adjacent field. The surviving passenger told the NTSB that the touchdown was “rough”. Accurate statement.

Speaking of rough, there were far too many NTSB reports with this wording as the probable cause: “The pilot said that the airplane touched down and then became airborne again and began to porpoise. The pilot tried to regain control and stop the induced pitch oscillations, but landed hard on the nose gear, substantially damaging the firewall.”

Engine trouble was the runner-up category, at 17 percent. We found multiple reports of engine failures from undetermined causes, while others were revealing. In one 182C crash, a post-accident examination of the engine turned up a piece of engine isolator gasket which become wrapped around the carburetor main fuel jet, while both magnetos’ distribution gear had cracked and were missing teeth. The NTSB determined the damage was related to engine backfire. Another 182 engine seized from loss of lubrication after the oil suction screen became clogged with debris, which included fractured portions of piston rings.

Despite the relative simplicity of a Skylane fuel system, a couple of pilots managed to take off with the selector in the wrong position. Still, several pilots learned that no matter how simple the fuel system is, if you burn all the fuel in the tanks, the engine will eventually quit.

We threw eight wrecks into the ambiguous “other” category, including a takeoff crash blamed on a clogged pitot tube, a hand-propping gone bad (it went into the side of a hangar, actually), a run-in with a bull during the takeoff roll in rural Arizona, plus a couple of wrecks which might have been avoided if pilots would have waited until the aircraft was parked before getting drunk.

There were also a handful of carb icing events, where pilots waited too long to apply carb heat. But perhaps the saddest of them all was the fearless student pilot who should have waited longer before launching into IMC. Like most 182 wrecks, that was no fault of the aircraft.