It’s easy to see why Meyers owners are so enthusiastic about their four-place singles. If speed is the goal, a Meyers brings it—well north of 180 knots for later models. Even better, occupants are we’ll protected thanks to a race car-like tubular roll cage. And for those looking for a classic, the Meyers 200 is a design that actually started taking shape in the 1930s and matured in the late 1960s.

When we looked at the Meyers market a few years ago, prices were sky high for models with meticulous restorations and modern upgrades and it seems that trend continues, with some fetching double or more than the typical Bluebook published retail prices. Want one? There aren’t many for the picking. In all, only 135 Meyers 200s were produced, and just fewer than 100 are still flying.

A WINNER FOR SPEED

In 1935, Al Meyers began work on his first design: a biplane called the Meyers OTW (Out To Win), which earned Uncle Sam’s blessing for use in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. Meyers then designed a two-place, retractable, low-wing taildragger called the Meyers 145. The 145 was a fast and efficient machine, achieving 145 MPH on the same number of horsepower. Only a handful of Meyers 145s were built.

The stage was set and the design eventually was modified into a four-seater, which is the 200. The prototype Meyers 200 flew in 1953, but it wasn’t until five years later that the airplane received its type certificate, and the 200 ultimately went on to win a number of speed records in its class. For production, the prototype’s carbureted, 225-HP Continental O-470-M engine was replaced with Continental’s fuel-injected, 260-HP IO-470-D.

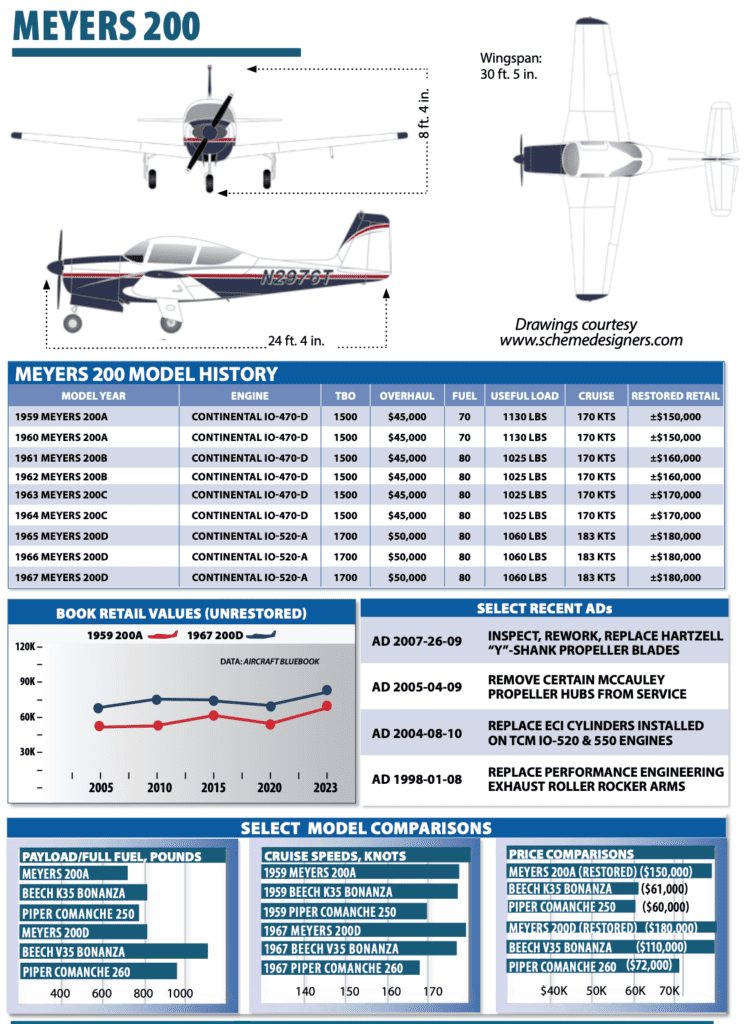

Production started with the 1959 model year, and moved slowly. At the time, there were a few direct competitors around: Piper’s Comanche 250 and the Beech Debonair and Bonanza. The Meyers was considerably more expensive than either the Comanche or the Debonair, and cost almost as much as the V-tail Bonanza while offering less load-carrying ability.

The 1959 and 1960 models were designated 200A. They had a 70-gallon fuel system, 3000-pound gross weight and an empty weight of 1870 pounds. Performance was on a par with the V-tail Bonanza: 170-knot cruise speeds and 1150 FPM climb rates. A total of 11 were built.

In 1961, Meyers brought out the 200B, incorporating minor changes including a different fuel system (a mere 40 gallons standard, 80 optional) and an improved instrument panel. Empty weight went up to 1975 pounds, though the gross remained 3000. Some 17 B models were produced.

The C model, introduced for the 1963 model year, got additional changes: a higher cabin roof, larger windshield and better interior. Only nine C models came out of the factory. But much more significant enhancements arrived with the 200D in 1965. The wings got flush rivets, and the IO-470-D was replaced by a Continental IO-520-A of 285 HP. The D model’s aerodynamic changes boosted the cruise speed significantly, to 183 knots, while the stall (dirty) dropped to only 47 knots. Takeoff roll and 50-foot obstacle clearance numbers also improved.The weight dropped a bit, too, to 1940 pounds empty, while the gross remained at 3000 pounds.

The design was sold to Aero Commander (later known as Rockwell Commander), which was a solid second-tier manufacturer at the time. Production run of 69 planes was achieved for the 1966 model year.

SYSTEMS, LOADING

Need to carry a lot of stuff? This probably isn’t the plane for you, but there’s a workaround, sort of. The passenger seat and the two rear seats can be removed quickly to accommodate cargo. There’s also a large baggage hatch on the right side of the fuselage. But the airplane cannot haul much—legally, that is. Throughout production, gross weight remained at 3000 pounds, with real-world equipped empty weights typically running around 2100 pounds. Add full fuel, and you can fit only about 450 pounds of people and baggage into the airplane and stay legal.

To climb aboard the Meyers, there’s a retractable step, complete with its own door, and a large, incongruous chrome assist handle jutting out from the side of the fuselage for grabbing on.

You don’t have to look hard to see these airplanes are different, and somewhat complex. Bring it to a shop that knows the model well. The landing gear and Fowler-type flaps are hydraulically actuated, and the flight controls incorporate push-pull tubes. There are two emergency gear-extension systems: a hand pump to supply hydraulic pressure and an uplock release mechanism. If the hand pump doesn’t work, the pilot releases the locks and slips the airplane, allowing aerodynamic loads to shove the gear down.

There’s a switch built into the circuit that prevents the starter from turning if the massive gear handle is not in the down position.

There are no squat switches, and pilots have inadvertently retracted the gear on the ground. After takeoff, you move the gear handle to the up position, then move it back to neutral once the gear is stowed to reduce pressure in the system. If you forget, there is an annunciator light to remind you.

At the heart of the airplane’s design and reputation are welded, 4130 chrome-alloy steel tubes forming the fuselage and center section. The structure runs from the firewall to the rear fuselage bulkhead and three feet out into the wings, where it supports the main landing gear assemblies. The rear fuselage section is of semi-monocoque design and construction.

Fuel in most Meyers 200s is carried in two main tanks and two auxiliaries. Each holds 20 gallons and the total usable capacity is 74 gallons. There’s only one fuel gauge, and it only reads the tank in use, so there’s no way to tell how much fuel is in one of the other tanks without actually selecting it.

FLYING IT, SUPPORT

The nosewheel is the same size as the main wheels, a design that makes the Meyers 200 a player for reasonably rough unimproved strips. Once off and cruising, stay ahead of it—the Meyers is a slippery, heavy bird that demands speed management. The never-exceed speed of the 200A is 208 MPH, and its maximum structural cruising speed is 165 MPH. Starting with the B model, these limits were raised to 236 MPH and 210 MPH, respectively. The elevator trim takes some getting used to when transitioning to a Meyers. It’s a vernier control mounted just underneath the three power controls, but it’s easy to make fine trim adjustments.

The controls are relatively heavy, thanks both to the push-pull tubes and to the short lateral throw of the yoke. Owners say that, due to a bungee arrangement in the control systems, little or no trim change is required with gear and flap extension.

Thanks to relatively high gear- and flap-extension speeds, the slippery Meyers 200 can easily mix with traffic in the pattern. In the 200A, the gear can be lowered at 165 MPH, and the flaps at 125 MPH. Gear-extension speeds for the B, C and D models are 170 MPH for normal operation or 210 MPH in an emergency, though the gear doors will likely come off. The Meyers isn’t certified for spins.

MARKET, MAINTENANCE

Impressively, there have been no ADs on the airframe structure, and the ones dealing with elevator trim mods and inspection of the landing gear have likely been done on all existing planes. Of course, the engine, prop and ignition systems are subject to the usual collection of one-time, shotgun ADs affecting other airplanes. In all, there are only 31 ADs applicable to the Meyers 200, a low figure for a 40-year-old design. Given the small number of airplanes in existence, it’s not surprising that there have been almost no service difficulties reported on the Meyers 200.

As for normal upkeep, owners report that they have few if any problems getting parts for their airplanes. They say that most parts requiring regular replacement are used on many other aircraft, so there is a good supply. Hands down the best resource when buying and owning a Meyers is the Meyers Aircraft Owners Association at www.meyersaircraft.org.

As for mods, the 200A can be upgraded to a B model by installing stringers in the tail, which permits higher speeds. The earlier models can swap the IO-470 engine for an IO-520A, bringing them up to a D configuration. Some have fitted the Continental IO-550 and a three-blade prop. A modified nosebowl with an extended profile and smaller air inlets is also available.

As thin as the market is, we found a couple of listings for nicely restored Meyers models, and you should plan to spend big. Dean Siracusa, a Meyers owner and guru (and the founder of Flying Eyes eyewear), said the market has never been stronger. “The Meyers market is as hot as all other high-performance complex airplanes,” he told us in early summer 2022. Most nice examples will sell for over $180,000.

Like any complex retrac, get an insurance quote before making a deal.

We went back to 1964 in our search for Meyers/Aero Commander 200 series accidents. We located a total of 45—meaning that nearly half of all those built have a damage history. We found very few fatal accidents—the combination of a roll cage design, a good restraint system and room for occupants to flail during an impact sequence kept many accident victims alive.

We found two areas of concern. First, there were 12 fuel-related wrecks. Most were due to the multiple tank fuel system design giving pilots the opportunity to screw up. Which they did with some regularity. A few simply ran out of gas. One found out he had water in the tanks once in flight rather than on the preflight.

The second area of concern was maintenance. There were four engine stoppages because the fuel system had not been maintained correctly or at all. In two accidents fuel line fittings were not attached correctly. In two the fuel lines themselves had deteriorated to the point that they were sluffing off pieces, which eventually clogged the lines.

Failure to properly install and secure the air filter during installation of a new engine and prop stopped the engine 300 feet up on takeoff. The pilot then stalled the airplane.

A segment of the exhaust pipe came loose from the heater muff, leading to an inflight fire. One Meyers threw a prop blade due to fatigue cracking emanating from a poorly repaired bit of damage to the blade.

A pilot experienced what he described as severe vibration during cruise. He slowed down—which reduced vibration level—declared an emergency and landed. After getting out of the aircraft he noticed that the left end of the elevator was hanging several inches below the horizontal stabilizer. A recent repair of “dents” in the elevator required work on the elevator and its outboard hinge. The technician doing the repair did not properly secure the hinge. It came loose during flight, leading to elevator flutter, which, fortunately, the pilot was able to reduce in magnitude by slowing down.

There were two cases of power control cables coming adrift and the engine rolling back to idle.

There were four gear collapse events caused by failure to maintain the system—including one in which the oleo strut on the right main was low and the pilot elected to depart anyway. The gear leg hung up upon retraction and wouldn’t extend on arrival, leading to a noisier than usual landing.

A pilot who disdained the superior occupant protection design of the 200 by deciding not to wear his shoulder harness paid for it with serious injuries when he got into PIO after a hard landing, ran off the runway and hit an obstruction. Not surprisingly, he jackknifed over the seatbelt and clobbered his head on the instrument panel.

There were only two runway loss of control accidents, a testimony to good design for ground handling and dealing with crosswinds. Four pilots did manage to touch down hard enough to bend their airplanes. One pilot stalled his Meyers on final approach.

One pilot experienced an electrical fire in flight. He was able to land safely.

There was a surprisingly low number of stupid pilot tricks, three.

One pilot did the VFR into IMC schtick with the unfortunately common and tragic ending.

One circled property he was interesting in buying until he hit the ground and one topped off a buzz job over a retirement party with an attempt at a barrel roll. It was unsuccessful.