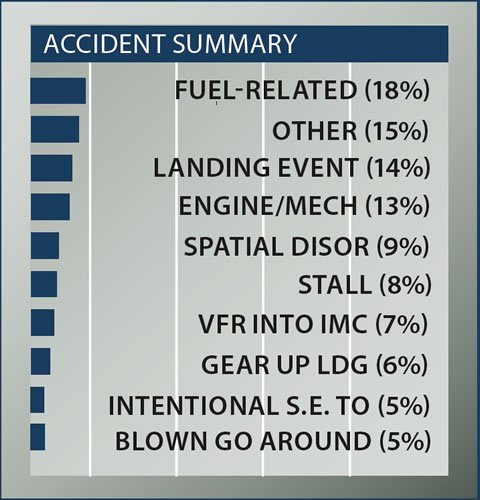

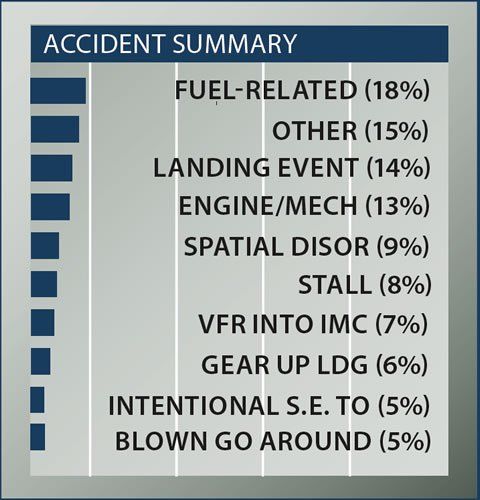

In looking at the most recent 100 accidents of the Cessna 336/337 we formed the opinion that there was little wrong with the airplanes, but had our doubts about some of the pilots who chose to fly them.

There is a school of thought that airplanes that are designed to be extra safe, such as the Ercoupe (cannot be stalled) or the Skymaster series (center-line thrust) attract pilots who rely on the design to overcome subpar skills and judgment. Our accident survey for the Skymaster and Super Skymaster produced results that seemed consistent with that school of thought.

Topping the causal hit parade was fuel-related events—every one pilot caused. In our monthly surveys we expect to see one or two accidents involving something wrong with the fuel system, here there were none. All but one was the result of a pilot running out of fuel or mismanaging a fairly simple system (there’s a main and aux for each engine—the aux tank can only be used in level flight), so that he did not get at fuel that was in a tank. The sole exception was water in the fuel the pilot didn’t drain.

In a few of the accidents, the pilot managed to run the tanks in one wing out of fuel (left wing tanks feed the front engine) and then did nothing when the associated engine quit—he did not attempt to cross feed to get fuel to the engine from the other wing and did not feather the prop on the dead engine.

Failure to feather was a factor in several accidents. A Skymaster is so air-kindly that it goes straight ahead when one engine stops, but the pilot has to feather the associated propeller, otherwise the airplane probably won’t climb and, as the density altitude goes up, may not hold altitude. Among the engine/mechanical-caused accidents, more than half the time the pilot did not feather the dead engine.

Judgment came into play in a few of the engine/mech accidents as the owner had either failed to perform engine maintenance for some time or it had been carried out, in one case, by mechanics who had had their certificates pulled previously for improper repairs.

One pilot pulled the wings off his Super Skymaster at the end of a high-speed buzz job. Seven, about twice what we usually see, tried unsuccessfully to fly VFR in IMC. Stunningly, five pilots attempted to make single-engine takeoffs and didn’t make it—in four of the cases others had tried to convince the pilot not to do it.

We saw no indications that a Skymaster pilot lost an engine on takeoff and didn’t realize it—the acceleration is dramatically different when the horsepower is halved.

Ten of the accident reports noted that the pilot attempted “operation with known equipment deficiencies,” including trying to fly IFR in IMC without a working attitude indicator. Three of the stall accidents involved flight at very low altitude. A 95-hour student pilot tried to take his family for a night flight in his 336; none of them survived his loss of control in the pattern.

The good news is that the 336/337 handles very we’ll on the ground, only two pilots lost control on the runway. However, nine landed so hard or bounced so badly they damaged their airplanes. There were three landing overshoots—in one case the pilot didn’t use the brakes until a passenger said to.