If you’re in the market for a used STOL (short takeoff and landing) taildragger, a Maule M-series model should certainly be on the short list of machines to consider. For years, tailwheel Maules have offered an impressive balance of utility and performance. On wheels, floats and skis, you can do a lot with a Maule—especially models with big engines.

In general, these airplanes are easy and forgiving to fly when in the air, but as our recent NTSB report scan revealed, the runway loss of control accident rate is distressingly high. Still, they’re relatively simple to fix and good at going slow but capable of decent cruise speeds, although the published speeds for many in the model line are considered humorously optimistic.

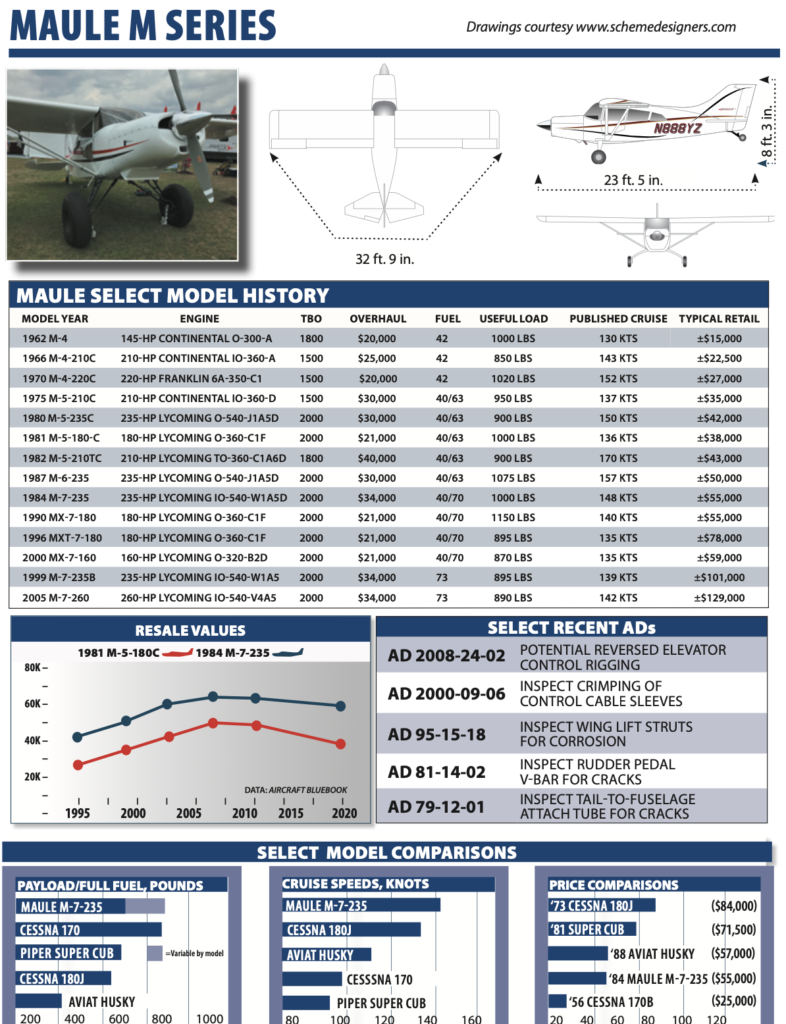

MODEL HISTORY

Inventor B.D. Maule started coming up with airplane designs when he was in the Army assigned to a dirigible base. He formed his first airplane company in 1941, but it didn’t last. The family business dates back to the 1950s, when Maule developed the basic design of the current series: a stubby-winged, round-ruddered fabric tailwheel machine with a welded steel tube truss fuselage and a metal spar wing, it bore striking similarity to the Piper Clipper/Pacer. It won an EAA prize at Rockford (before the EAA was at Oshkosh). Maule obtained FAA type certification in 1961, calling the airplane the Bee Dee M-4. It was powered by a 145-HP Continental O-300-A.

Mr. Maule has passed on, but his company hangs on after decades spent tweaking the design to create new models that aren’t much different from each other except mostly for their engine options (from that first fixed-pitch Continental to 160-, 180-, 210-, 235- and 260-HP Lycomings, a 210-HP Continental and a 220-HP Franklin), landing gear choices (oleo struts or heavy-duty spring gear) and cabin door configurations.

On some models, there also have been constant-speed and fixed-pitch options and a choice between fuel injection or a carburetor. There’s a tri-gear model and was even a turboprop.

The airplanes evolved from the first M-4 Jetasen into the M-4 Rocket, which had a 210-HP Continental, into the heavier 2300-pound Strata Rocket with a 220-HP Franklin. In 1973, the Lunar Rocket replaced it with a return to the 210-HP Continental. The Astro Rocket, meanwhile, had joined the fleet in 1970 with a 180-HP Franklin. It lasted two years, but 180-HP versions reappeared as one of the M-5 variations in 1979, morphing, in 1985, into both the M-6-180 and MX-7-180, which had the M-7’s longer fuselage and wings and longer ailerons to maintain roll response. A 160-HP Lycoming version was offered from 1995 to 2004.

The M-5 first appeared in 1974 with either a Franklin 220 HP or Continental 210 HP as options. It had a larger tail area and the choice of 63-gallon tanks instead of 40. The demise of Franklin Engine Co. brought Continental’s 235-HP O-540 into the picture in 1977. Starting in 1998, a 260-HP version of the Lycoming O-540 was also offered.

The M-6 appeared in 1981 with structural changes that increased gross weight to 2500 pounds, including wings that were two feet longer than the M-5’s. It offered more flap settings, up from two positions (20 and 40 degrees) to four: 24, 40 and 48 degrees and minus 7 degrees for reduced drag in cruise.

M-5s were made until 1988; the last new M-6 was made in 1991. There was an M-8 briefly (1993).

The most recent flagship model is the fuel-injected 235-HP M-9-235. It has a Lycoming IO-540-W1A5 and structural reinforcements in the wing, fuselage and landing gear, giving the aircraft a 2800-pound gross weight. That’s a 300-pound increase over the M7, which has the same four-place cabin configuration. Maule says to plan on a 1100-pound useful load. It’s a go-places cruiser with four hours of fuel endurance and can accomodate 100 pounds of bags or anything else you can fit inside. The multi-mission M9 carries two adults, seven hours of fuel and 250 pounds of gear. There’s also the M-9-260, powered by the Lycoming O-540-V4A5.

The 180-HP machine is the MXT-7-180. It has a Lycoming O-360-C1 aluminum spring gear with a hydraulic nosewheel assembly. Useful load in it is 935 pounds.

USED MARKET PRICING

If something in the current lineup isn’t in the cards and if you’re shopping the used market, sifting through the dense Maule model line is a chore. Still, we think early-model Maules (and even later ones) are decent buys as taildraggers go. As one example, the fall 2020 Aircraft Bluebook puts a 1977 M-5-235C at about $38,000.

The Bluebook shows an average retail price for the earliest M-4 of $15,000. Prices range up to $32,000 for a 1973 M-4-220C. The first M-5s run from around $34,000 with the first Lycoming O-540 variant to about $39,000. Prices rise for various models through the mid-1980s ranging from just above $50,000 to $60,000 with the O-540 variants the priciest.

The first 180-HP models (1979-1981 M-5s) fetch $36,000 to $38,000; later versions run in the $40,000 plus range up to around $46,000 for the last year of the M-5, 1987. A 180-HP, 2010 model M-7 is valued at $145,000. And, 235-HP M-7s run from $57,000 average retail for the oldest (1982) to $170,000 for a 2010 model, according to the fall 2020 Bluebook. Low-time models sell for more, while ones that worked hard in the backwoods may fetch less.

PERFORMANCE

Yes, you’ve seen the images. More than once, B.D. Maule took off from inside his company’s hangar in an M-4, breaking ground before getting to the door and transitioning into a steep climb once outside. We are aware that others have repeated the demonstration. His successful marketing message was that this baby gets off the gravel bar and climbs away over the ridgeline like a rocket. And it does.

The Maule wing does love to fly and the higher-powered models can leave the ground in somewhere around 250 feet when light (a couple of hundred feet more for the 160- and 180-HP models). At Vx with 20 degrees of flaps, they climb away at a pitch that will make a Cherokee pilot blanch. The combination of high power loading (plenty of horsepower for the weight hauled) and low wing loading (lots of wing area for the weight) do the trick.

Maule has long marketed a 250- to 300-foot ground roll, and then qualified it by saying it was at reduced weights. We do not know how much the weight has to be reduced to get that performance. Maules are, in our opinion, simply STOL airplanes with very good takeoff performance—so we always felt the company should have altered its advertising and give the ground roll at gross weight, rather than some arbitrary, reduced weight.

Moreover, the company’s approach to publishing performance information extends to cruise numbers, especially in its earlier models. Owners have consistently told us that they were nowhere near reality. As one owner once said, “My M-5-220C couldn’t reach book cruise numbers in a vertical dive with the clutch in.”

Some years back, Aviation Consumer loaded up a Piper Dakota and an M-5-235C to compare them. In cruise, with both engines firewalled, the monocoque-hulled Dakota was 5 MPH faster despite book numbers that showed it to be slower. It also climbed better, again despite book numbers that would have given the steel-tubed Maule the edge.

Readers report leaving the ground in the 235-HP version within 500 feet and climbing out at better than 1000 FPM every time. As for a 180-HP model, the Bluebook’s specs give an M-5 a 900-FPM climb.

Saying all that, in the aircraft data page (page 25) we provided published cruise speeds, but they should be taken with a large grain of salt. For example, the Franklin-powered M-4-220C has a published cruise speed of 152 knots—the reality is closer to 120-125 knots.

Owners report that cruise speeds are all over the place, from 140 to 165 MPH (a lot of Maules have airspeed indicators marked in MPH) for the 235-HP versions. One reason, in part, is that earlier models had highly variable airspeed indications because static ports were affected by small differences in the cowling caused by manufacturing variations and wear. The ports were in the aft part of the cowling, and an ice pick was the tool of choice for adjusting them by creating a lip on one side of the hole or the other to eliminate high or low readings.

Readers say 120 to 125 knots and a 12- to 13-GPH burn at cruise are typical for the 235-HP Maule at 65 percent power. That would be about 10 knots slower than a 182Q burning about the same amount of fuel. A 210-HP M-5 owner said 120 MPH at 60 percent was standard.

While the two rear doors and removable rear seat option make it easy to throw a lot of big stuff in the back, some well-equipped Maules can be left with a useful load down around 800 pounds. The legend is that the airplane easily outperforms its book load limits. However, takeoff accidents involving failure to break ground on the available runway, impact with obstacles after takeoff and failure to climb after takeoff indicate that the airplanes will not carry everything you can put in the doors.

The low wing loading translates into low stall speeds on the Maule (33 knots for an M-5 with 40 degrees of flaps, 30 knots on an M-6 or M-7 with 48 degrees) and low takeoff and approach speeds.

That means a crosswind will be that much more of a factor than it is in a faster airplane. A slideslip to prevent drift and firm, quick rudder inputs to keep the nose straight are vital to avoiding groundloops. Owners reported that the light wing loading makes the airplanes susceptible to gusts and recommended not trying to land in a crosswind above the demonstrated number.

Another issue is getting enough drag to allow a steep descent over obstacles without building up speed. The post-1981 Maules with the greater range of flap settings address this concern—but watch the flare. As with any airplane approaching the runway steeply, slowly and with a lot of drag, timing will be critical and power will probably be necessary to prevent a pancake or hard landing.

Maules are considered to have lots of control power but not too much stability—a moose-chasing pilot’s dream. Some have been annoyed, however, by a tab on the rudder that automatically deflects to counteract yaw when aileron is applied. The problem is it works well at only one speed, maybe around 90 knots. At slower speeds, you’ll still need to apply rudder to keep turns coordinated.

At higher speeds, too much rudder is applied automatically, which makes for “proverse yaw” or, to put it simply, a skid. “I have owned two Maules so far,” one owner wrote in reply to a chat-room request for comments. “There is not much to complain about. The only thing I would change is to get rid of that tab on the rudder. It is there for those who don’t know how to fly coordinated and is a pain in a crosswind.”

The problem is an apparent reduction in rudder power at slow speeds just when you need rudder power, say for a slipped landing.

CABIN DWELLING

Some ask why buy a Piper Super Cub when you can buy a Maule and take your friends with you? Walk around a tailwheel Maule and you get the point. While not cavernous, Maules have a generous cabins. But these aren’t Bonanzas or Centurions. Access to the two front seats is normally awkward, as can be expected in any airplane that sits at a tilt.

The Maule’s nose pokes lower in profile than many other tailwheel airplanes, however, so pilots can taxi it without S-turns to see ahead. Access to the rear seats (for up to three people in some models) and the baggage area is exceptional with big doors on each side. The pilot sits behind the wing, so lateral visibility on turns is poor.

Plexiglas doors and a skylight are a factory option that give spectacular visibility down and straight up and received raves from readers. Maules are noisy, especially those with bigger engines, so bring your best headsets—and warm clothes when the temperature drops. Heating is from a standard exhaust muff, but the back seats in older models, especially, get cold in winter.

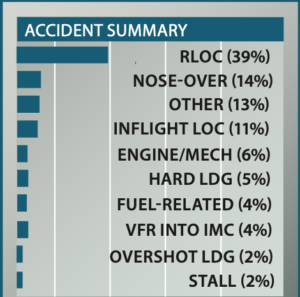

When we started reviewing the 100 most recent tailwheel Maule accidents, the smart money said that we’d see the results of risk-taking pilots getting a little too unwrapped with their airplanes.

The smart money was right.

We’ll get right to it: A full 65 percent of the Maule accidents were landing-related—runway loss of control (RLOC), overshot landings, nose-overs, hard landings and loss of control in flight during a go-around following control issues on landing.

That’s huge; however, we are not putting the causal finger on a problem with ground handling characteristics of the Maule tailwheel line. To start a more nuanced examination of the landing accidents, we note that a healthy proportion consisted of crashes directly related to where the pilot chose to land. Welcome to Alaska.

Of the 14 nose-over events, half were due to terrain that was soft, rough or snow-covered. Two resulted from brake master cylinders that hadn’t been maintained and their condition caused the pistons to stick and the brakes to lock up. The other five came at the end of an RLOC adventure. We do not believe that the Maule tailwheels have any proclivity toward flipping over when things get ugly due to some problem with landing gear geometry. The rate of nose-overs was less than we observed on the Husky and Super Cub lines.

All things being equal, the rate of RLOC accidents overall for the Maule tailwheel line is consistent with other tailwheel airplanes—way more than the J-3 Cub and less than the Cessna 190/195 series.

More than a few Maule pilots elected to land on a road or other very narrow surface where the margin for wandering off center-line was thin. Not surprisingly, they exceeded the available margin and hit something. A couple of pilots stuck the landing but ran into problems on takeoff. One landed on a road to check on his cattle. On departure, he drifted to the left and hit a road sign but got into the air. Concerned about structural damage, we think he then made a good decision to carry out a precautionary landing. Unfortunately, that didn’t go well and he wound up in some trees.

The remainder of the RLOC accidents could almost have been written with a rubber stamp. At some point during the landing roll the upwind wing lifted and a directional excursion began. That points out the necessity to keep aileron deflection appropriate for the crosswind anytime the wheels are in contact with the ground.

In the good news department there were only six engine power loss accidents—that’s unusually low—and only four fuel-related accidents. One was due to fuel contamination in an airplane that had been sitting outside, unflown, for nearly a year. Another fuel-related accident involved a pilot who didn’t use a checklist prior to takeoff and forgot to turn the fuel selector away from the off position. The engine quit shortly after takeoff. Only two accidents were attributed to stalls, also a low rate.

Our heart went out to the guy who set up for, and made, a lovely landing on a lake. After it was too late for a go-around, he remembered that he’d swapped out the floats for tundra tires.

MAINTENANCE

Most Maule owners report that dispatch reliability and general upkeep is reasonably good. In general, Maules are considered sturdy and reliable with few maintenance issues, although we’ve seen some electrical quirks with newer models we’ve had the chance to ferry long distances. Still, the factory in Georgia is friendly and responsive. It buys and sells used Maules, so parts are readily available. The best news is that no Maule is an orphan airplane.

Corrosion in wing lift struts prompted a 1995 AD requiring biennial inspections and treatment or replacement, if necessary. Many owners have opted for replacement. Crimping on control cable sleeves, problems with an aileron control pulley, fuel line corrosion and the rudder trim tab control were among the subjects of other ADs.

Cracking paint on the fuselage fabric has been a complaint. So have cracking mufflers. Some tailwheels began breaking after gross weight went to 2500 pounds in 1981, a problem corrected on later models with beefier gear.

Fabric has to be inspected and eventually replaced. It’s not always easy to find a shop that still does it. The factory will, of course, but it will be a big expense that should be considered when shopping for older models.

And, look carefully at previous fabric repairs. Not all are created equal and it’s certainly a skill that not every mechanic has.

Upkeep for the familiar engines is straightforward, although consistent service difficulties and short life spans were reported for the mufflers and exhaust stacks. Look at the them carefully during prepurchase evaluations and also during annual inspections.

MODS, OWNER GROUP

Vortex generators to reduce stall speed even further are a common mod to make Maules even better in the STOL department, available from Micro AeroDynamics Inc. (www.microaero.com or 800-677-2370). Otherwise, the factory (www.mauleairinc.com or 229-985-2045) offers lots of options, from full swing-up windows, glass doors, window and skylight, three-blade prop for the 235- and 260-HP models, straight and amphibious floats, skis, IFR packages, autopilots and engine analyzers.

The website www.maulepilots.org bills itself as nonprofit and unconnected to any commercial operation. A regular in its chat room is “Jeremy the Maule Guru,” former bush pilot and now longtime dealer Jeremy Ainsworth, whose own strictly commercial website is www.maules.com.

OWNER COMMENTS

We bought a new, 2002 M-7-235C with a 235-HP Lycoming O-540 in 2003 and we love it! As they say, there are faster airplanes, there are airplanes that carry more and there are airplanes that cost less, however, nothing matches this well-rounded “Renaissance airplane” in doing so much, so well.

After looking at the type of flying I do, I decided on a tailwheel, high wing with at least two doors. I felt having a tailwheel and low stall speed would minimize forced landing risk. I read all the airplane ownership books I could get my hands on, including the UAG compilation, and narrowed it down to the Pitts S2C, Aviat Husky, American Champion series and the Maule. The Maule had the best combination of features, plus side-by-side seating—important to my wife and me as we are both pilots and share the duties.

I learned that airplanes are like tents—sure, you can put two guys in a two-seat airplane, but you can’t do it with bags and 3.5 hours of gas. In the Maule you can (or three adults and a bit of baggage). Useful load for ours is 761 pounds, so the fifth seat in the back isn’t practical.

With 235 HP, the airplane is ridiculously overpowered, at least until you get to density altitudes above 10,000 feet. If you are not going to the high country or wanting to climb up high quickly, the 180-HP versions will save you some gas money and give you more useful load.

We’ve taken ours all up and down the East Coast, across the Midwest, to Idaho, Colorado and California and still love every minute.

The observer doors—clear from top to bottom of the door sill on both front doors and the middle door (right side)—can be retrofitted. The “picture window” on the left side of the fuselage and the skylight have to be built in at the factory. What a view! The only way to get a better view is to fly open cockpit.

Likes: Fun; inexpensive compared to a twin or retract; manual flaps; solid cross-country and IFR flyer. The tailwheel makes me a better pilot. It has great visibility and is quiet outside with a three-blade prop. Oversize tires mean landing on grass, gravel or up to six inches of snow is a snap. Everybody likes to see a Maule show up. B.D. Maule was a genius, and the family has steadily improved the product over the years without overextending the company.

Gripes: Loud inside (need ANR headsets); easy to overfuel because it’s hard to see the fuel level as the tank nears full; crosswind capability; mufflers and exhaust stacks—have replaced several. The ones repaired by aftermarket shops such as AWI lasted much longer than the ones I got from the factory.

When the flap notch bracket got bent, I found that the Maule factory doesn’t keep everything in stock—however, they are still in business and recently they’ve seemed more responsive. At six feet tall, I’m glad I’m not taller when it comes to fitting in the airplane.

Tricks we’ve learned: Maximize hot airflow to the front seats by cracking open the front fresh air cabin vent; pick your fuel stops by price, but if there is more than a 12-knot crosswind, go elsewhere and don’t worry about fuel price. Install an oil quick drain; when the Maule tailwheel starts to shimmy, replace it with an ABI tailwheel.

Andy and Sandy Travnic – via email